The Prophetic Imagination of St Martin

Walter Brueggemann is a famous Old Testament scholar whose most significant work is probably ‘The Prophetic Imagination’, first published in 1978.

In his book, Brueggemann takes, as his starting point, the idea that the church is always subject to ‘enculturation’, by which he means a process whereby the church absorbs and adopts crucial elements of the culture of the society in which it operates and is thereby cajoled away from its faith. The church, so argues Brueggemann, needs to break free of this enculturation by drawing on its faith, on scripture and on the way this scripture has been collectively understood over the centuries and, instead, exercise a prophetic imagination which has to find a balance between two things:

- Criticism of the way the world is, primarily by using lament which he argues is the most effective way to cut through the numbness that humanity exhibits in the face of its deathly existence.

- Energisation of the people of God by presenting and acting out alternative ways of living and believing in hope and expectation of a better future in the Kingdom of God.

Criticism alone is not enough. It is not enough just to be angry with the world. But neither is energisation enough, because a refusal to acknowledge, identify and lament the brokenness of the world separates the vision of the Kingdom of God from our daily reality of living in the world as we know it.

Brueggemann offers Moses as an example of a prophet who exercised such a prophetic imagination. Moses preached against the Kingdom of Pharoah. He didn’t so much criticise it as undermine its very basis of existence by calling out the slavery in which his people were held as being illegitimate in the eyes of God. He then energised his people by leading them towards a promised land and teaching them a new way of living by God’s word.

Later, when the monarchies of Israel re-introduced the economic exploitation of God’s people in defiance of God’s laws, Jeremiah was called to be a prophet who criticised this kingdom by lamenting its future destruction and then second Isaiah was called as a prophet to articulate a radical energizing by imagining a better future for a forgiven and redeemed Israel.

Jesus, of course, combined the two elements of prophetic imagination in a perfect balance between dismantling the deathly world through his crucifixion and energizing a new God-given future through his resurrection.

I am going to apply Brueggemann’s concept of a Prophetic Imagination, which incorporates both criticism and energisation, to the life of St Martin because I believe his life and ministry was remembered by the church as a way of holding onto this idea of prophetic imagination and embedding it in the life of the church. To help me with my studies, I have referenced sources that I have drawn on, hopefully in a way that will not be too distracting to the reader.

Martin (316-397) was a Christian in the fourth century, called to be a disciple of Christ at a time when Christianity was gradually being adopted as the state religion of the Roman Empire. Martin was first ordained to be an exorcist. He was then attracted to monasticism, at a time when this tradition was hardly heard of in Western Europe. He became a monk and founded his own monastery. From there he reluctantly answered a call to become Bishop of Tours in what is now France, thus combining elements of monastic ascetism with church leadership and engagement with the world.

During his own lifetime, a church historian, called Sulpicius Severus (363-425), wrote a book called the Life of St Martin. This book recounted the story of how Martin came to faith and how he exercised his ministry both as monk and bishop, including the many miracles that attended his life. After Martin’s death, Sulpicius wrote a second book with more stories about Martin including some accounts of further miracles performed by Martin after his death, (through his relics). These books were widely read and the further accounts of the live and miracles of St Martin were written in the following two centuries, creating a tradition that was widely known across the church, especially in France, Germany, Italy, The British Isles and the Low Countries and then became embedded in the culture of these parts of the world through the celebration of Feast of St Martin, otherwise known as Martinmas.

Sulpicius Severus was called to a life of ascetic scholarship after the death of his wife. He was concerned about what Brueggemann might call the ‘enculturation’ of the church in the form of church leaders who were too focussed on worldly matters, status and material goods (Stancliffe). He was attracted to Martin as a figure who was faithful to the tradition of the church and resisted this enculturation and who in the words of Brueggemann, was

“a child of the tradition, one who has taken it seriously in the shaping of his or her own field of perception and system of language, who is so at home in that memory that the points of contact and incongruity with the situation of the church in culture can be discerned and articulated with proper urgency.” (Brueggemann, 2).

Such was his regard for Martin, that Sulpicius became his follower, travelling to stay with him in Tours where he began to record his own interactions with him as well as the stories that other people told about him. Sulpicius believed that this was a life worth recording and sharing in the church – a life which embodied how the church should be. By calling Martin a saint, Sulpicius, was setting in motion a new tradition. Hitherto, churches could only be dedicated to the apostles of Christ and to martyrs. Martin did not die for his faith, he lived for it, and after Sulpicius had recorded that life, living a life of prophetic imagination became a new way to becoming a saint, a life that others might follow.

The work of Sulpicius contains a number of elements which I will attempt to summarise here:

Martin’s coming to Faith and his call to a Holy Life

Martin was born in modern-day Hungary, then part of the Roman Empire. His parents were not Christian, but Martin announced his faith in Christ to his astonished parents when he was only ten years old.

Martin’s faither was a retired officer in the Roman army and, at the age of 15, Martin, also was conscripted into the army, also as an officer.

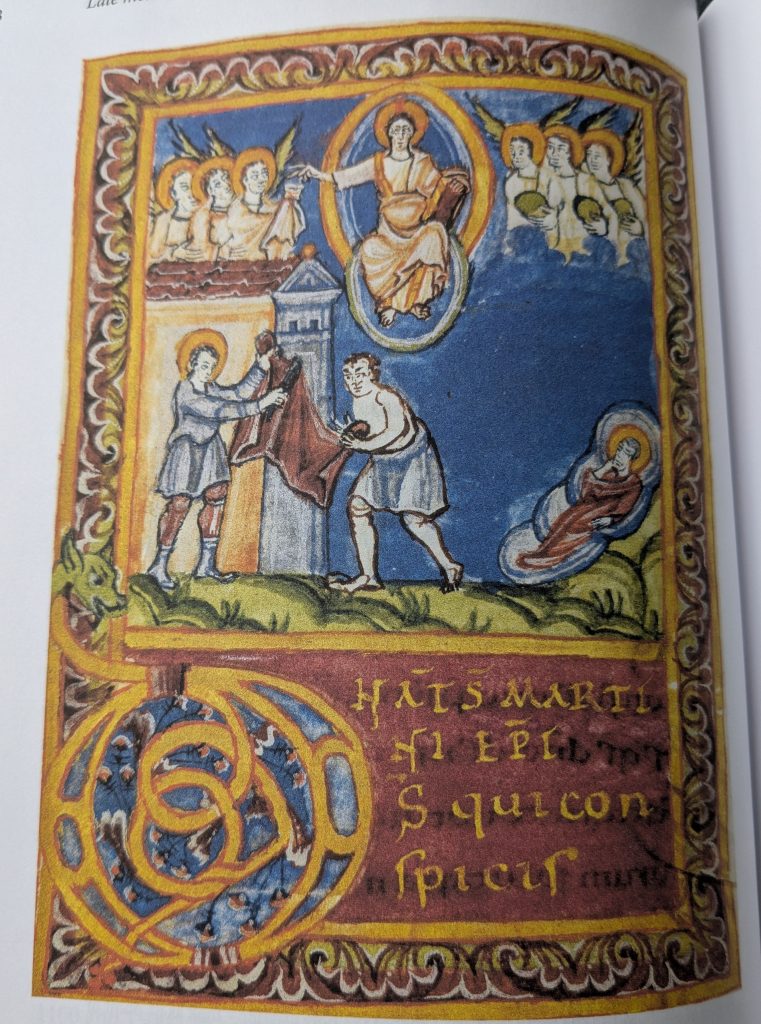

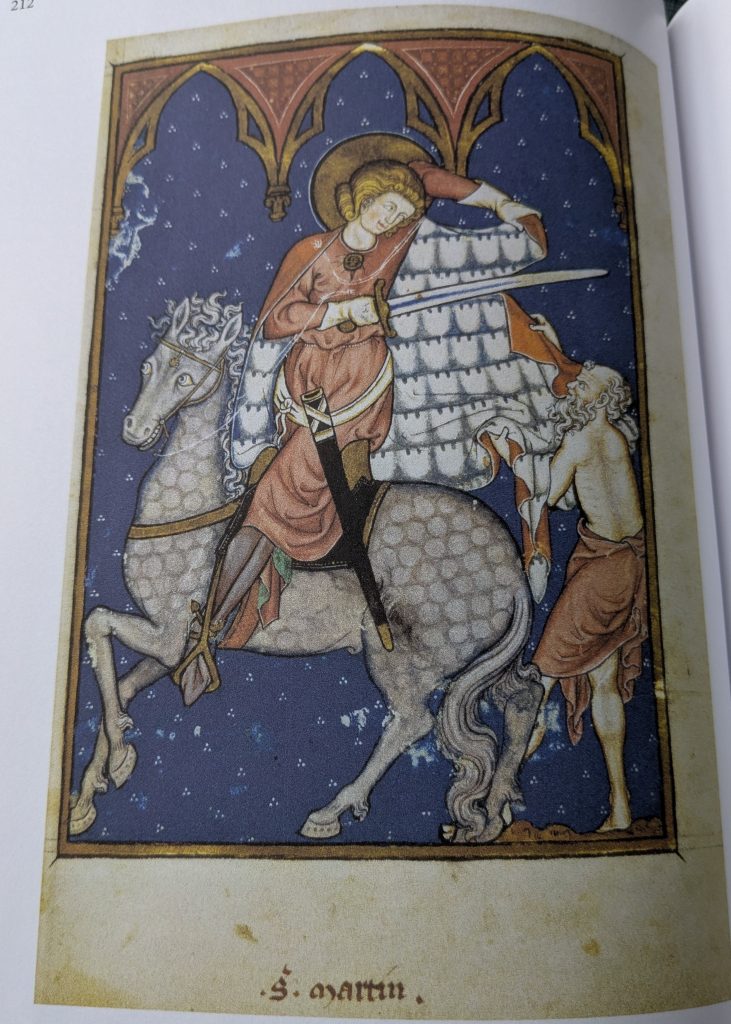

One night, at the gates of the city of Amiens, now in northern France, Martin was approached by a beggar. Martin had no money left so he cut his military cloak in two and gave half to the beggar to keep him warm. This story is called the Charity of Martin and it is the episode of his life most often depicted in churches today. That night, Jesus came to him in a dream, bearing the cloak in order to show that he had been the beggar. After this dream, Martin presented himself for baptism.

When the Emperor Julian came to inspect the army, Martin stepped forward and announced that as a baptised Christian he could no longer fight in the army. In order to prove that this stance came from a position of faith rather than cowardice, Martin offered to stand unarmed in the front rank of the army at the forthcoming battle. The Emperor took him up on this offer. On the day of the battle, the enemy asked for a truce so that no battle was fought.

In these accounts we see Sulpicius presenting to us the unexpected nature of God’s call on Martin’s life, the strength of his faith as demonstrated by his willingness to hold onto his faith and resist enculturation, and his commitment to sacrificial love and nonviolence which were key to establishing his holiness.

Martin’s Ascetism and Prayer

After he had left the army, the church wanted to ordain Martin but, in a manner which turns out to be characteristic of Martin’s faith journey, he considered himself unworthy and so he was ordained instead as an exorcist, the lowest rank of ordained minister.

Sulpicius then tells the story of Martin’s attraction to a monastic life, a tradition that was little known in the Western European church at that time. Martin lived a frugal and ascetic life, constantly praying and performing healing miracles for the sick and possessed.

When the people of Tours wanted him as their Bishop, he initially refused so that the people of Tours had to trick him by sending one of their number to ask him to heal his sick wife. When Martin emerged to perform this healing miracle, he was abducted and taken to Tours where he was installed as Bishop.

A Bishop and a Monk

By presenting Martin as a Bishop and a monk, (Farmer) Sulpicius is describing a man who at one and the same time retreated from the world and set himself apart from it while also engaging with it and seeking to intervene in it and shape it.

At this time the main understanding of monasticism came from Athanasius account of the Life of Antony of Egypt who was one of the desert fathers who lived an ascetic life of prayer in a place of remoteness, the Sinai desert, cut off from the polluting culture of Egyptian cities. Sulpicius was describing a life of a man who was also committed to monasticism but was dragged reluctantly into church leadership and, therefore, into engagement with the world.

Arriving in Tours, Martin established a new monastery at Marmoutier, across the river from Tours itself. This community became the place that Martin would retreat to – his base. He would emerge from Marmoutier to carry out his work as bishop in Tours and across his diocese (and sometimes beyond) continuing to wear the ascetic clothes of a monk, to remind himself and others where he came from and from where he drew his spiritual strength.

By retreating from the world in this way and distancing himself from it, Martin was implicitly criticizing it. But by venturing out into the world to articulate a new reality, Martin was also energizing it. Thus, we may say that Martin articulated a prophetic imagination to use the words of Brueggemann.

Church Leadership and the Kingdom of God

In the account of Sulpicius Severus, Martin’s main work as a bishop, founding new churches and mentoring priests forms the backdrop to the stories that he really wants to tell which mainly concern miracles of healing, including bring people back from the dead, other miracles which prove Martin’s holiness and his many interactions with the rich and powerful and the poor and excluded which speak of Martin’s humility, his emphasis on including all people in God’s love and his courage in speaking truth to power.

This articulation of the Kingdom was central to Martin’s work as a bishop, according to Sulpicius Severus. Martin always behaved with humility, sticking firmly to the principle of non-violence and there was always a happy ending, either because people responded to the sincerity and integrity with which Martin spoke and behaved or because God intervened to show people that Martin was speaking with his authority.

Two stories from many are typical of the whole account:

Martin was on his travels, traveling as usual in his simple monk’s clothing and riding a donkey. He passed by a group of much richer travellers who were riding horses. Martin’s donkey upset the horses being ridden by these rich travellers and so they set upon Martin and beat him. Whereupon, their own horses sat down as if rooted to the spot and would not move. The people attacking Martin, realising that this behaviour of their horses was something out of the ordinary, recognised Martin and they knelt before him begging his forgiveness which he happily granted. (Freeman)

On another occasion, Martin was dining as a guest of the Emperor and the Emperor, in order to publicly honour his guest, passed him the first cup of wine. Martin kissed the cup and passed it onto the humble priest who was accompanying him, as a way of honouring the priestly role before the Emperor. (Freeman)

Standing up for tolerance – The Priscillian heresy

Sulpicius devotes a lot of his book to Martin’s dealings with the Emperor Maximus over the Priscillian heresy. Priscillan was a theologian in Spain who articulated a theology that drew on a number of Zoroastrian themes and had moved quite a long way from the orthodoxy we are familiar with today. found many adherents in Spain and some of his followers were chosen to be bishops.

The orthodox bishops of Spain appealed to the Emperor to depose these bishops and execute them. Martin was very much opposed to involving secular rulers in internal church affairs and also opposed to the death penalty being used. He travelled to Trier to persuade the Emperor to change his mind and went as far as refusing to share communion with the orthodox bishops. This greatly upset the Emperor, who wanted a united church to support his claim to be Emperor and so he rescinded two death sentences in return for Martin agreeing to share communion with his rivals. (Maitland)

Afterwards, Martin felt guilty about having compromised his principles. Sulpicius records Martin’s anguished conversations with an angel sent by God to console him and claims that Martin subsequently retreated from church politics and never again attended a synod. (Stancliffe)

The Continued Development of the Martin Cult after his death

When Martin died, his remains were brought back to Tours and kept in a basilica in Chateauneuf, just outside Tours, where they became the focus of a pilgrimage centre. Many more miracles were attributed to Martin via his relics and stories of these miracles were recorded and publicised, most notably by Gregory of Tours in the sixth century. This was a time when churches that held relics could grow incredibly quickly (Abou el Haj).

By then, St Martin had become something of a patron saint for the Kings of France after King Clovis attributed his victory over the Visigoths to the intervention of St Martin (Maurey). When a cloak was discovered, that was apparently the very cloak that Martin had shared with Jesus who had appeared before him at Amiens in the form of a beggar, the French kings commanded that the cloak be carried before their armies when they went into battle. (Farmer) The story of St Martin sharing his cloak with a beggar became the most depicted story from the life recounted by Sulpicius Severus. Increasingly, the depictions in painting and sculpture began to show Martin more and more as a medieval knight (Maurey).

Another key adaptation of the Martin story was supplied by Venantius Fortunatus who wrote an epic poem around 575 based on the stories told by Sulpicius. But Venantius introduced another dimension to Martin by depicting him as a saint sitting in heaven to whom believers could pray directly for salvation. Humble Martin was now enthroned in heaven. (Livarsi)

The Legacy of Martin

By the end of the sixth century the details of Martin’s life were widely known across the church. The most famous story was the so-called ‘Charity of Martin’, a story of generosity and seeing in a poor beggar am image of God. While this story confirmed Martin’s social status as a knight or military officer, it was also a story challenges the world as it is and points to the generosity and love of the Kingdom of God. The traditional German song, ‘St Martin ritt durch Schnee und Wind’, sung by children at the Feast of Martin on 11th November tells this old story and includes a line from Jesus himself, ‘Hab Dank, du Rittersmann fuer das, was Du an mir getan!’ which we may translate as, ‘Accept my thanks, good knight for the service you have done to me.’ (Timm)

However, the focus on the charity of Martin, as well as emphasising his elevated military status, also takes attention away from one of his most dramatic stories when he appears before the emperor and refuses to fight in the battle on the basis of his Christian faith. But it would be unfair to assume that this story was not also cherished by the church through the ages. Studies of the liturgy used in the church to celebrate the Feast of St Martin included references to this courageous act (Maurey) and there is a beautiful set of embroidered altar frontals made in Burgundy in the fifteenth century which record no less than thirty-two episodes from the life of St Martin including those stories which record his commitment to non-violence.

Many cathedrals in Northwestern Europe were dedicated to St Martin including Ypres, Utrecht and Mainz (Freeman). A section of the cathedral in Mainz includes a memorial to each of their bishops and they are grouped around a statue of St Martin, as if he is a model whom they all followed (Arens). There is no doubt that the stories of St Martin recorded by Sulpicius Severus were widely known in the church across Northwest Europe.

And not only in the church but in the communities they served. The Feast of St Martin, or Martinmas, falls on 11th November, the day of his funeral and this happened to coincide with a traditional start of the Anglo-Germanic winter (Walsh) This was the day when animals who were not likely to make it through the winter were slaughtered, geese which had been left to graze in marshes were gathered in, and in areas like Burgundy and the Rhineland it was also the day of the first wine pressings. This combination of sausage and wine made for a great festival and the many stories of Martin became woven into the traditions; especially those that inverted the usual power relationships and emphasised community cohesion and solidarity. New stories about Martin were told, in which he played the part of the joker who challenged the way people thought and made them think about themselves and in each other in new ways. (Walsh)

Today, in Britain, 11th November is Remembrance Day, marking as it does the anniversary of the Armistice that ended the First World War. It is tempting to wonder whether there is a connection. Did the French generals want to pin the armistice oton the day when they celebrated a martial French saint? Had some memory of the saint who refused to fight somehow inserted itself into the peace negotiations? In some parts of Germany and the Low Countries, they even start the St Martin’s Day festivities start at 11am.

There is no evidence of a human intention to make 11th November St Armistice Day because it was also St Martin’s Day. (Maurey) And plenty of evidence that suggests that this was just when the negotiations finally came to a point when they could sign an agreement. But what a wonderful coincidence it is!

St Martin is a saint who had a prophetic imagination. And he exercised his imagination in word and, above all, in deed, to lead the church away from the enculturation that always threatens to take it away from its calling. Remembrance Sunday is a complicated day for the church to negotiate. It is a day when the dangers of enculturation are very real. What a gift it is, therefore, to have a human example of a saint who resisted enculturation and remained faithful to Jesus Christ whatever the pressures and whatever the dangers. May he continue to inspire devotion, clarity of thought and courage as he has done for so many centuries.

Abou el Haj, Barbara The Medieval Cult of Saints – Foundations and Transformations (Cambridge, 1994)

Arens, Fritz Der Dom zu Mainz (Darmstadt, 1998)

Eckersley, Rosanna An Awkward Fit? Winifred Knight’s Scenes from the Life of St Martin of Tours, Canterbury Cathedral in Visual Culture in Britain Vol 118 Issue 2 (2017 pp192-216)

Farmer, Sharon Communities of St Martin – Legend and Ritual in Medieval Tours (Ithaca, 1991)

Freeman, Margaret The St Martin Embroideries – A 15th Century Series illustrating the Life and Legend of St Martin of Tours (New York, 1968)

Livarsi, Lorenzo Venantius Fortunatus’s Life of St Martin – Verse Hagiography between Epic and Panegyric (Bari, 2023)

Maitland, Margaret Life and Legends of St Martin of Tours 316-397 (London, 1908)

Maurey, Yossi Medieval Music, Legend and the Cult of St Martin (Cambridge, 2014)

Stancliffe, Clare St Martin and his Hagiographer – History and Miracle in Sulpicius Severus (Oxford, 1983)

Timm, Jutta Leuchte auf, mein Licht – Martins und Laternenlieder (Ravensburg, 1997)

Walsh, Martin W. Martin of Tours – A Patron Saint of Medieval Comedy in Saints – Studies in Hagiography edited by Sandro Sticca (Binghamton, 1996)

I have reflected at length about this essay, Robin, and I remember you preaching on St. Martin on Remembrance Sunday a few years ago. Your presentation and content about St. Martin is very good, but I am not convinced that St. Martin is always appropriate for Remembrance Sunday.

I consider that the pastoral role of a minister of the church is of equal importance to the prophetic role. As a Church of England priest, I took Remembrance Sunday services over many years, and I preached at most of them, and I adopted the pastoral role. At a parish church where I served as Vicar for 18 years there were in the congregation most Sundays two men whose experience of war were key. The first was a man who had served with the RAF in the Second World War as a flyer, and who then worked as a school teacher until retirement. He spoke openly with me about his anger – about the loss of life that he saw in war, about the loss of years of his life as a young man to military service, and about the lack of understanding about the war that he saw in the children whom he taught. He was still an angry man, and he vented his anger on me. The second was a man who had been a squaddie in the British Army: he had done three tours in Northern Ireland, one of them over Christmas, and that still rankled. He was a nervous and worried man: he had seen and done things that continued to disturb him.

I consider that the primary task of the minister on Remembrance Sunday is to show military veterans, serving military people, and the families and friends of those who have died in war that he or she understands and values the dedication to duty that epitomises military service.

Thank you Jon. One of my next blogs will focus on the pastoral role of the minister on Remembrance Sunday.

Thanks for shining a light on Martin. the reluctant bishop and the non- martyred saint