Our Remembrance tradition in Britain began as a response to the carnage and suffering of the First World War. Although there have been other wars since then, the First World War continues to shape our national remembrance. The poppy itself is an image from the post-battle trench landscapes of Flanders. Images of First World War soldiers are attached to lampposts, printed on flags and painted on the side of pubs and trucks. In those churches and communities where the names of the war dead are read out, it is the names from the First World war that dominate, because it’s the war that claimed more lives of British soldiers than any other.

In recent years, the frequency with which we encounter these images, has increased quite significantly. People think of more and more ways to display poppies and the number of images of First World War soldiers also seems to increase every year. The natural result of this is that people assume more and more that the events of the First World War have a profound relevance to our lives today. Politicians and clergy try to capture what this relevance is. Quite often they arrive at a formula that these men died for the freedoms which we enjoy today. How else can you explain why we are having this strong focus on the First World War? It must have been important. It can’t have been senseless. Why else would these images be all around you in early November every year?

It seems to me that this recent prominence in First World War imagery in our churches and communities seems to be accompanied with relatively little understanding of why the war was fought and what the world was like for our ancestors in those days. People hearing that all these men died fighting for freedom would probably be surprised to hear that most of the men who died fighting for the British Empire in the First World War did not have the right to vote or any hope of ever getting it according to electoral laws of the time. They would probably be surprised to learn that British war aims included the acquisition of Palestine and Iraq and a great many men died specifically in pursuit of these conquests.

In church contexts, there are many other important matters that remain unexamined in our Remembrance observances. The national churches across Europe played an enormous role in supporting their respective states in fighting the war. How do we reflect on that today? Some Christians, on the other hand, opposed the war and, in some cases, refused to fight. How do we reflect on their witness? And where was God in all this? How did the example of Jesus Christ and the urgings of the Holy Spirit affect the events of those terrible years? Can the church really say that it is engaging in remembrance if it is not really remembering what happened and cannot bring itself even to begin to ask these questions?

Apologists for the British state’s entry into and participation in the First World War focus on Britain’s treaty obligations to France and Belgium and the German violation of Belgian neutrality and subsequent war crimes directed against Belgian civilians. If you visit the Flanders Fields in Ieper/Ypres in Belgium (and I recommend a visit to this excellent museum), not unnaturally, the Belgian experience of the First World War is at the forefront of the exhibits. We are reminded that Belgium reiterated its neutrality just before German invaded anyway. The small Belgian army put up a determined resistance. The German army committed many war crimes. In the end, the German army occupied the whole of Belgium except for a small corner which included the town of Ieper/Ypres. 600,000 Belgians died in the war including many civilians. Ypres itself, although only briefly captured by the Germans, was almost totally destroyed. Standing in Ieper/Ypres, it is very easy to understand that the British army in the First World War fought alongside the army of a small country that had been illegally and brutally invaded by a powerful neighbour. The British army in the First World War was, in this sense, fighting for freedom.

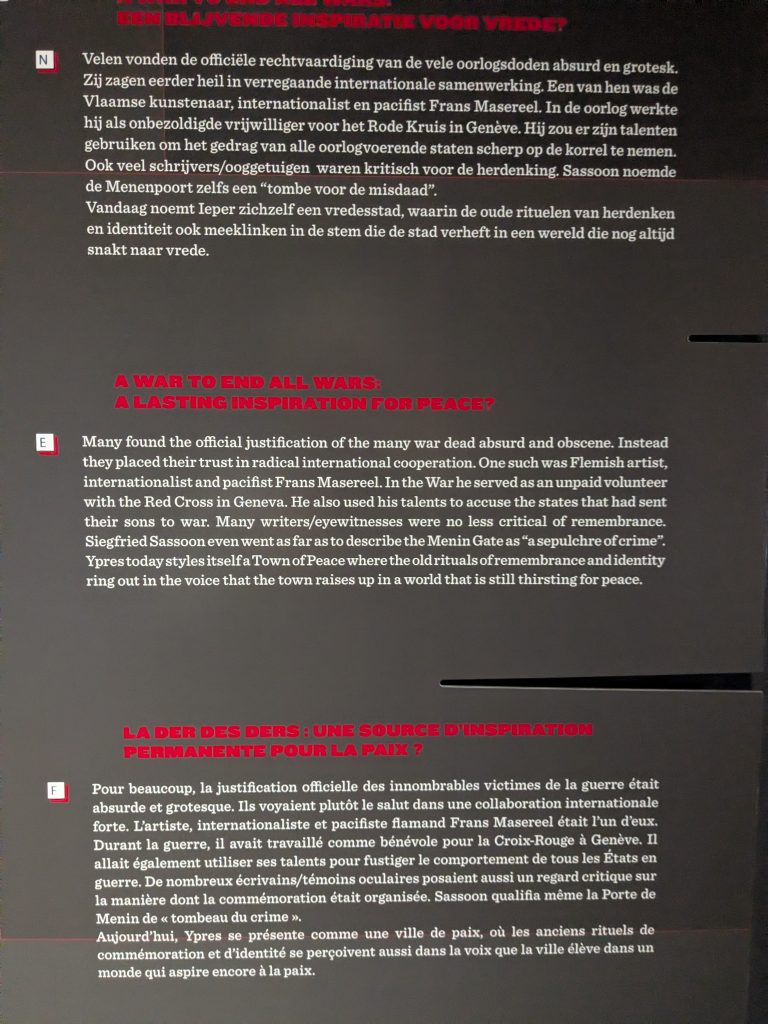

But the museum in Ieper/Ypres does more than tell the story from a Belgian perspective. Exhibits are explained in four languages: Flemish, of course, but also in French, English and German. Visitors are told about the rise of nationalism across Europe, the crucial role of imperialism in the economic development of Europe and the arms race that took place between European nations in the lead into the war itself. This is not a museum that seeks only to tell a national narrative. It is attempting a more universal and holistic understanding of the war that had such devastating consequences for this pretty little town.

I timed my visit to Ieper/Ypres in order to be able to attend the 11th November commemoration event at the famous Menin Gate close to the centre of town. The Menin Gate is a large stone arch which seeks to commemorate the names of all the soldiers who died in the Ypres Salient on the Belgian side of the war who have no known grave in the many cemeteries that surround the town. The year of my visit was 2025, and I record this because one thing I have learned is that remembrance events do not remain the same year after year.

The ceremony was hosted by the Last Post Association who organise a minute silence every evening at 8pm at the Menin Gate. Before the minute silence, the last post is played by a bugler of the local fire service. Applications from outside the town to play the last post are accepted but the tradition is that such visiting bugle players are enrolled as a volunteer in the local fire service and wear the uniform of the fire service when they play the last post. This is a tradition that extends a welcome to all while also insisting politely that people submit to local control of the ceremony.

This similar balance between an inclusive invitation and local control was also evident in the 11th November event that I attended. A variety of uniformed formations assembled in the space between the Roman Catholic Cathedral Church of St Martin and the Anglican St George’s Memorial Church. Some looked very much like regimental bands from the British Army. Other armed forces were represented including Belgium and Canada. A large contingent of Sikhs joined the procession in a formation that felt more like an expression of Sikh culture than a specific military body. It felt like any group that wanted to be part of the procession from the two churches to the Menin Gate could join. The pipe band of a Scottish regiment was especially impressive. What looked like a somewhat rogue freelance bagpipe player standing on the ramparts next to the gate chipped in when there was a lull in the music. And nobody moved him on.

Once at the gate, it became clear that the President of the Last Post Association, Benoit Mottrie, was in charge, as he introduced contributions in English and Flemish. He gave a short speech which was subtly unlike speeches you might expect to hear at a war memorial in Britain.

He began by asking us all to remember the sacrifice of those who died in the battles round Ieper/Ypres and the principles for which they died. He mentioned peace and he mentioned freedom. Standing in a Belgium that is free and at peace today, this seemed to make sense and is what you might expect him to say.

But then his comments took, what was for me, an unexpected turn. He invited us to reflect on whether all these people really had to die. He asked us to remember the wars taking place today and he listed some of them. He pointed out that the peace that these people had sacrificed their lives for was fleeting and fragile. And finally, he asked us to reflect on what it takes to prevent wars taking place in the first place and to recommit our efforts to build peace in the world.

I was struck that you could take these comments at a number of different levels. But for all his listeners, Benoit Mottrie’s words represented a challenge.

Why might a country that suffered a brutal invasion have a more nuanced take on the First World War that the one you might experience in a church or war memorial in Britian on 11th November? I think it must surely be at least in part due to the lens with which Belgian society looks at the events of the First World War, ie the lens of the Second World War and the post war settlement. In the Second World War, Belgium surrendered after only 18 days of fighting (and the Dutch surrendered even more quickly, after 4 days fighting). This was and remains a controversial decision, but it was a decision made in order to save lives and it must have been a decision affected by the memory of the many people who died in the First World War. Belgium today is very much a country at the heart of the European Union and the economic, cultural and political integration which this institution provides. For Belgians, the priority is not, how do we resist an invasion from a powerful neighbouring state, but rather, how can we contribute to a system in which our neighbouring states will remain at peace.

I wondered what the many British visitors to Ieper/Ypres were making of Benoit Mottrie’s comments and, indeed, the whole ceremony. Because British remembrance culture is really quite different to the act of remembrance, I took part in in Ieper/Ypres.

And this is, in part, because in British remembrance culture there is very little real reflection about what the British state did in the First World War. Defending the right of Belgium, a small neutral nation that had been invaded, this was part of the story. But really only a part. War aims are complicated to start with and usually get more complicated as a war progresses. In any case, the British Empire is not famous for championing the independence of small nations. It was, at the time, engaged in a long battle to block Irish independence and had almost reached a new peak of dominance across the world, a dominance that depended in denying freedom to other nations. Indeed, its war aims in the First World War included a plan to acquire Palestine, Arabia and Iraq. Modern day Tanzania, Namibia and Papua New Guinea were also added to the British Empire at the end of the First World War. The British interest in maintaining the neutrality of Belgium was not based on a desire to defend freedom but rather came from a strategic objection to prevent a continental power in Europe dominating the English Channel and the North Sea coast. So why don’t we say that before we read out the names of the soldiers who died? Why don’t we reflect on their deaths in the context of what actually drove them to their deaths?

You were probably taught in school that the First World War was triggered by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. This may be regarded as the trigger event. But it was only a trigger because of the imperialist assumptions and aspirations of the great powers. The Austro-Hungarian Empire’s idea of what justice for the Archduke might look like was a settlement that would bring the entire state of Serbia into their orbit. The Russian Empire which had already subjected many nations saw this as a threat to their own expansionist aspirations. In the event, Russia’s allies, Britian and France, promised Istanbul and its environs to the Russian Empire. The German Empire could not permit a Russian attack on Austria-Hungary and France, emboldened by its treaty with Britain, could not permit a German attack on Russia. All the diplomats involved who could have taken steps to prevent war breaking out shared a common assumption. They were working in the service of an empire that needed to expand further and further at the expense of other nations.

Let’s just remember here the words of Land of Hope and Glory which is still sung in Britian today: Singing about the British Empire, the people sing, ‘Wider still and wider, may her bounds be set. God who made her mighty, make her mightier yet.’ When you ask people why they sing these words today, they will often tell you that they don’t really mean these words literally, they just sing it because it’s a tradition and an expression of pride in their country. The thing is, people used to sing these words and mean it. And all the imperialist powers had their own versions of this song. How can we expect states with this kind of national culture build a world of peace? And to move away from this kind of national culture requires conscious effort and a significant element of challenge. Who will make this effort? Who will meet this challenge?

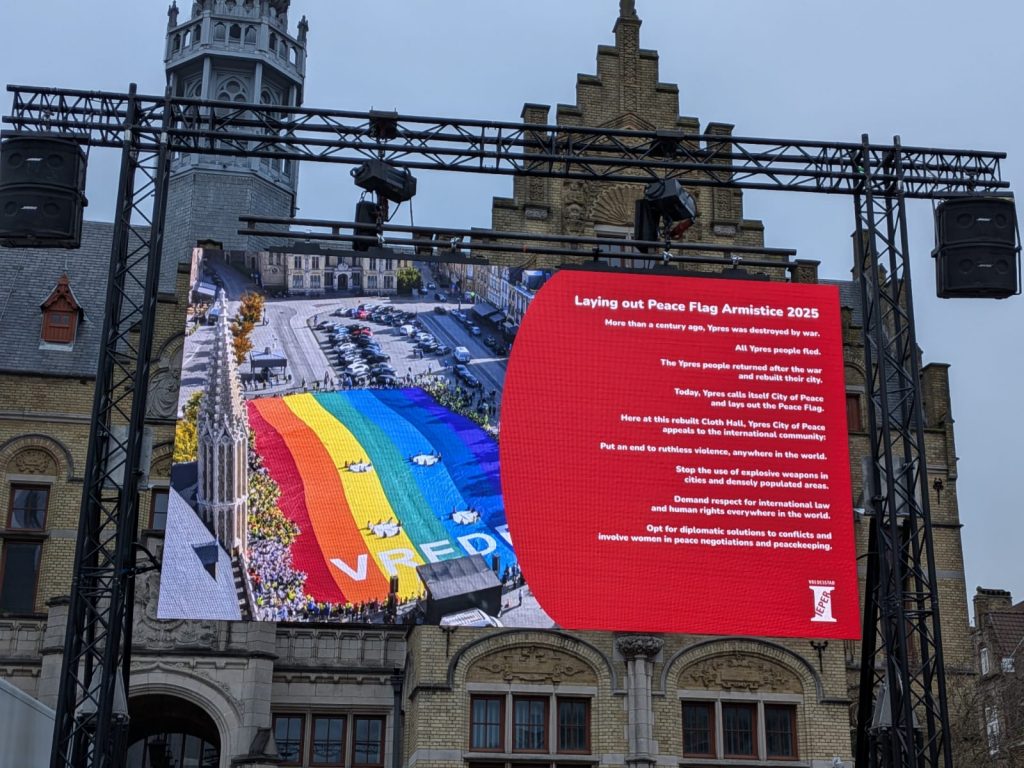

In 1914, international structures were built for war not for peace. What might have happened if Britian had made it clear to France that they were on their own if they pursued war with Germany? What might have happened if Germany had told Austria-Hungary they were on their own of they didn’t back down over Serbia? Millions of lives might have been saved. It is this kind of ability to make the right decision when a crisis comes that the Last Post Association invites us to imagine. As well as poppies and military bands and uniforms and medals and salutes, their remembrance ceremony includes a large multicoloured flag in the main square with the word, ‘peace’ written on it. And as well as abide with me and the last post they invite a teenage girl to sing ‘Imagine’ by John Lennon.

The second verse of John Lennon’s famous song begins: Imagine there’s no countries. It isn’t hard to do. Nothing to kill of die for. As people from around the world assemble in Ieper/Ypres, it is a actually possible to imagine this. But Lennon goes on in that verse And no religion too. Imagine all the people living life in peace.

Because the church didn’t really make a decisive witness for peace in the First World War. Churches did not make a decisive witness for peace despite the courageous attempts by some Christians, despite the folk memory of the Christ Child that lived in the hearts of so many soldiers in the trenches and despite, even, the powerful peace movements that did, in the end play such a decisive role in bringing the war to an end, without any significant participation from the churches.

Have a read of these words:

Kill the enemy. Do kill them; not for the sake of killing, but to save the world, to kill the good as well as the bad, to kill the young as well as the old, to kill those who have shown kindness to our wounded as well as those fiends …As I have said a thousand times, I look upon it as a war for purity, I look upon everyone who died in it as a martyr.

These are actually the words of Arthur F. Winnington-Ingram who was Bishop of London in 1915. He was proclaiming a holy war – a jihad, if you like. The Bishop was a staunch supporter of the war effort throughout the war. He is credited with raising two while regiments. He urged his curates to enlist. He opposed the legal rights of conscientious objectors. He had his equivalents in all the states that were belligerents in the first World War. So while he was encouraging British soldiers to kill, German soldiers received the same encouragement from most of their religious leaders. And Winnington-Ingram was far from alone In Britain. His views were mainstream. Similar sentiments were expressed by Anglican clergy in particular throughout the country.

Despite this lead, some Christians in Britain did refuse to fight in the war. They were mainly Quakers and non-conformists – Anglicans had the additional burden of explaining to the military tribunals why they thought their conscience prevented them from fighting when their bishops said they should fight. Some conscientious objectors accepted noncombatant roles or jobs making munitions, while others didn’t. Some were badly treated. One conscientious objector from New Zealand was dragged to the front line in France by cables attached to his ankles. From there he was immediately hospitalised.

Then, of course, there is the Christmas truce which broke out at a number of places along the front line in 1914. For many years this was dismissed as a sort of urban myth but more recently historians who have studied letters soldiers sent home, newspaper articles and orders given by the military to prevent such truces have come to the conclusion that they did happen. The pattern was usually the same – the German soldiers would sing their Christmas songs on Christmas Eve and British and French soldiers would join in. Having established their common humanity and relationship with God through his Son, Jesus Christ, fraternisation in various forms broke out. Some of these truces lasted for weeks. Despite the best efforts of the military authorities, further truces broke out at Easter 1915 and again at Christmas 1915. After which they sadly petered out.

There is much here that churches could reflect on when we make the First World War the object of our remembrance. We could reflect on the responsibility born by religious leaders for the scale of the violence and killing. We could reflect on the decisions individuals made to go and fight or to refuse to fight. But, astonishingly, all these things are dropped from the narrative.

Which is even more amazing when you stop to consider how the First World War ended.

When we talk about the First World War as an industrialised war, we tend to think about the machinery of war that caused such devastation; the machine guns, the barbed wire, the tanks, the artillery, the gas and so on. This industrialisation gave rise to an unprecedented scale of horror and death. But it was also an industrialised war in the sense that many of the soldiers were industrial workers and they lived in countries with strong labour movements with a recent history of taking collective strike action. This led to the First World War, probably to a greater extent than any other war before or since, being brought to an end by mass mutinies: soldiers refusing to fight.

The obvious example of this was the Russian Revolution. It was the slogan, ‘Peace! Land! Bread! that gave the Bolsheviks the leadership of the Soviets in the key cities which brought about the October Revolution, a repudiation of Russian war aims, a unilateral Russian withdrawal from the war and a declaration of freedom for all nations. This then created an example for the soldiers in other armies to follow. The French army experienced a serious mutiny in 1917 that seriously undermined its capacity to undertake further offensive action. In 1918, mutinies in the Bulgarian army forced the Bulgarian state to request an armistice which then left the Ottoman capital Istanbul open to the imperialist armies of Britian and France. This in turn led to the German request to President Wilson of the United States for an armistice.

Interestingly, when President Wilson asked the British government what terms an armistice would have to include, the British cabinet struggled to arrive at a collective view. The perceived inability of the French to continue the war, the collapse of popular support for the war at home, the need to keep the German army intact so that it could fight bolshevism in its own country; these were all considerations taken into account. Negotiations with the German government over the terms of an armistice dragged on until the sailors in the German fleet took decisive action and took control of their ships in a mutiny at sea. Returning to port, some of the ringleaders were arrested whereupon there was a popular uprising of sailors and soldiers in Kiel and Hamburg to set their comrades free. This then led to uprisings across German industrial cities with Soviets of workers and soldiers established in a number of locations. In Berlin the Kaiser abdicated and fled the country as a republic was hurriedly declared. In these circumstances, the German state had no choice but to accept the French terms and an armistice was signed.

What we are marking on 11th November is an armistice agreed because hundreds of thousands of soldiers and sailors refused to fight any more. It takes courage to fight. It arguably takes even more courage to mutiny. When you agree to fight you risk death. When you mutiny you also risk death but without the weight of support from the state and the society in which you live. Were it not for the courage of mutineers in Russia, Germany and Bulgaria, many more British soldiers would have died than in fact did. But, again, none of this historical record is reflected in our commemorations at war memorials. And it is most unlikely that you will hear this astonishing story in church of the mass international movement for peace which brought a brutal war to an end without any conspicuous Christian involvement. You will not hear the story of the war that came to an end because people refused to fight.

Why don’t we ever hear that story?

First of all, for the church, it is a difficult story to tell. The church is not the hero in this story. At times, it played the role of villain. And although we have all the language we need for this story, language of penitence and faith in the mercy of God, let’s face it, the church doesn’t tend to use this language when it really counts.

The second reason for not telling this story is actually, when we talk about the First World War, our heads are already thinking about the Second World War. We are projecting back onto the First World War concepts that our society has embraced to make sense of the Second World War and what happened after that.

And the third reason is, we are bringing memories of more recent wars to our remembrance events and these memories have not yet been worked up into a coherent narrative. And it is possible that they never will.

Attending the commemoration event in Ieper/Ypres in 2025, it was apparent that there were many visitors from the United Kingdom and a significant number of these visitors were ex forces. So, on the one hand, we have the community of Ieper/Ypres with its own carefully researched history and consensus about what we have learned. And then we have all these visitors from another country and another remembrance culture, including former military personnel. Some openly wearing their medals, hats, badges and uniforms. They want to tell the world that they are ex forces. And others who wear no identifying items but whose military background becomes obvious more gradually.

What was interesting about the Last Post Association in Ieper/Ypres is that they will continue with their own remembrance culture. They happily include others from other nations so that the overall event is a collection of sometimes jarring thoughts and emotions. But they don’t hold back from saying what they need to say for fear of upsetting people who might be thinking something different. They do not feel an obligation to feel pastorally sensitive to what the veterans might be thinking. Whereas, I think when we gather at cenotaphs and in churches in Britain, and we know veterans will be present, we worry, I think, about what we can say about the First World War because we know that what is said will be heard in the context of wars that have only recently ended and we have only just begun the process of trying to understand them. And so we say very little. And even though we say very little, we sometimes manage to say things that aren’t really true.

I wrote earlier that the church doesn’t want to tell a story in which it is not the hero. But actually, the church shouldn’t be thinking about telling stories where it is the hero. It should be thinking about telling the story of Jesus. If we are telling the story of the First World War, then we should be asking where was Jesus in that war? Where was the Holy Spirit at work? Was Jesus in the trenches, in the submarines or in the conscientious objector’s cell? Was the Holy Spirit with the men who went over the top or with the men who turned round and shot their own officers? Or was the presence of God in all these places? And if the Holy Spirit was in all these places, where was it leading us? And where is it leading us today?

There is an astonishing coincidence in the history of the First World War. 11th November, armistice day is also the Feast of St Martin. Not only that, it is traditional in the low countries and the Rhineland for the festivities of Martinmas to start at 11.00am on that day. In other words, at the exact moment, that the guns stopped firing at the end of the First World War. I have read a lot of books about the armistice searching for any evidence that this time and date was chosen because of its significance in the Martinmas tradition. The conclusion I have come to is that it was a complete coincidence. By which I mean there was no human intention in picking this exact same moment to stop the fighting. And of course, in my theological tradition, an extraordinary coincidence can be understood as a sign of God’s Holy Spirit at work.

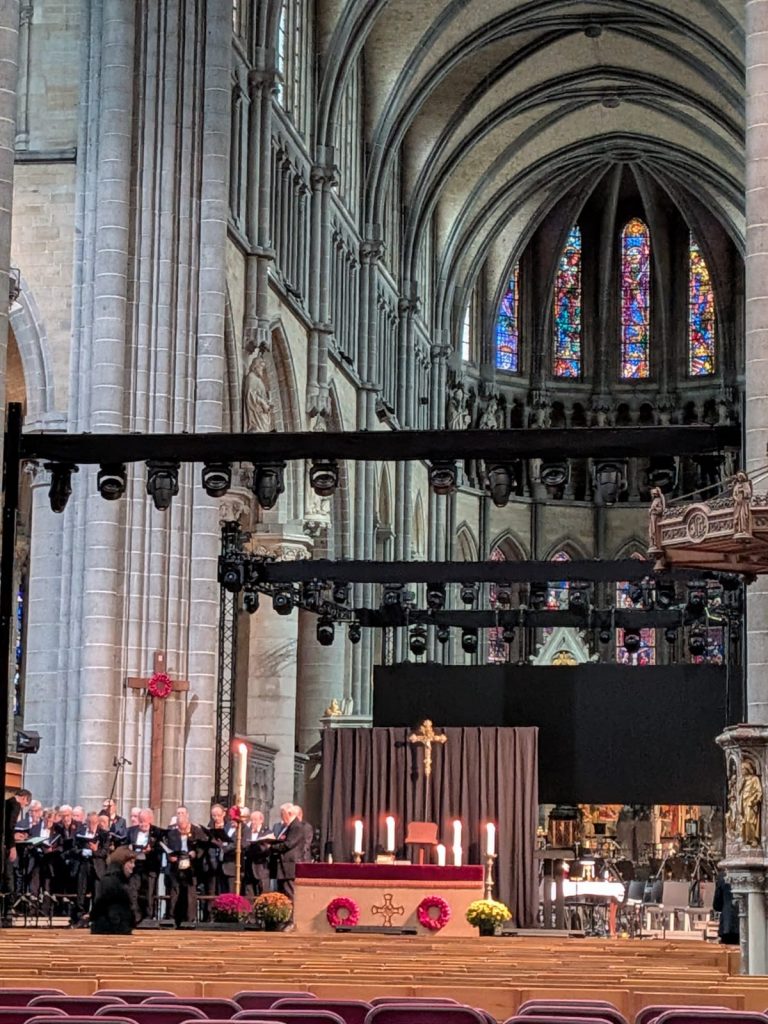

Before I went to the Menin Gate for the remembrance ceremony, I attended mass at St Martin’s church, the former cathedral of Ieper/Ypres. It was a very moving service with a truly international congregation. The priest reminded us what happens in the Eucharist. We remember the past, that Jesus died. We celebrate the present, that Jesus is risen. And we look forward to the future, that Jesus will come again. The Gospel reading was the parable of the sheep and the goats which is read that day because of its association with St Martin. In the parable the king rewards those who showed kindness to others. He tells them that when they showed kindness to others, they were showing kindness to him. They already knew for themselves what the right thing to do was. And now the king was inviting them into his kingdom.

The priest asked us to remember those who had died and looking ahead to the coming of God’s kingdom to hear the faith that God has in our ability to build peace which Jesus teaches in this parable. That was the priest’s final message. We can build peace. We can build peace today. He asked us to hold hands to say the Lord’s Prayer. And then we shared the body and blood of Jesus Christ which he gave to us.

Thank you, Robin, for this accomplished essay.

I write as a Church of England priest who retired three years ago after 34 years in parish ministry, and, over the last 30 years in ministry, having taken one or more service every Remembrance Sunday.

Over those 30 years I saw a steadily increasing number of people attending Remembrance events – both church services and wreath-laying at a war memorial: there is something in the air that compels an increasing number of people in the UK to engage with Remembrance Sunday ritual.

At the same time, there is greater appetite now than in the recent past for books, television programmes and other media which forensically dissect the history of Britain and the British Empire, or which reveal a much more nuanced understanding of British social history than has been portrayed conventionally in the past. Critics call this ‘doing Britain down’ and ‘hating Britain’ because it does not uphold the inherited national mythology of British exceptionalism. Such critics often expect the Church of England to be upholders of this mythology, whereas many clergy engage in their ministry with those who pay the price of others’ success and this makes them sceptical of the narrative of British greatness. Even so, a monarchic nation needs a story to tell which can unite its population around its monarch because only the monarch may declare a state of war.

Despite the popularity of a more nuanced approach to the British myth, the number of people who engage in the ritual of Remembrance Sunday increases. So a revisionist approach to history does not cut through to peoples’ need to engage with the impact of 20th Century warfare on the Sunday nearest 11th November. In my experience, Remembrance Sunday gives people the opportunity to engage directly and intimately, and in the safe setting of an established ritual, with the individual service men and women (mainly men) in the Great War who were cannon fodder, able seamen lost at sea, magnificent men in their flying machines who fell to earth in their burning ‘kite’. On Remembrance Sunday, there is little to no interest, I suggest, in the geo-political dynamics of why these people were fighting and what was the ultimate aim of the war. Those who engage with Remembrance Sunday identify with the Tommies who sang “We’re here because we’re here because we’re here”: they had no idea where they were, or why. And those in church and at the war memorial feel that powerlessness and they thank God that it was not them. And they worry about the shifting geo-political dynamics of the present age and fear that they, or their sons and daughters, may be conscripted to fight in future wars.

I do question the relevance of your incisive and compelling historical analysis of the Great War to understanding Remembrance Sunday, but I suggest that such work may serve peace-making.

As for Christian peace-making, there must, surely, be a role in Britain for the church which is like your description of the Armistice Day event at Ieper / Ypres, and like the museum at Ieper / Ypres that you describe. I suggest that the national myth, which is enshrined in the monarch who is the Head of the Church of England, is so powerful that the Church of England would find it hard to make any headway, but that should not prevent the church from trying. You have majored on the Great War as the origin of Remembrance Sunday, but, in my experience, those who engage with Remembrance Sunday ritual also bring with them the many 20th Century conflicts that came after the Great War. There may be no coherent narrative of these conflicts but I don’t think that there needs to be one. Robin – you are the man to do this!

That was so very interesting Robin, thank you so much.

I learned a lot.

I had relatives on my husband’s side who were practicing Quakers who refused to fight , but one I know became a fire warden in the last war.