A few days before Remembrance Sunday 2025, I went with my father to visit the town Geel in Belgium. We wanted to visit the grave of Major Harry Pye, my father’s uncle and my great-uncle. He is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Geel. He lost his life in the battle of Geel in September 1944.

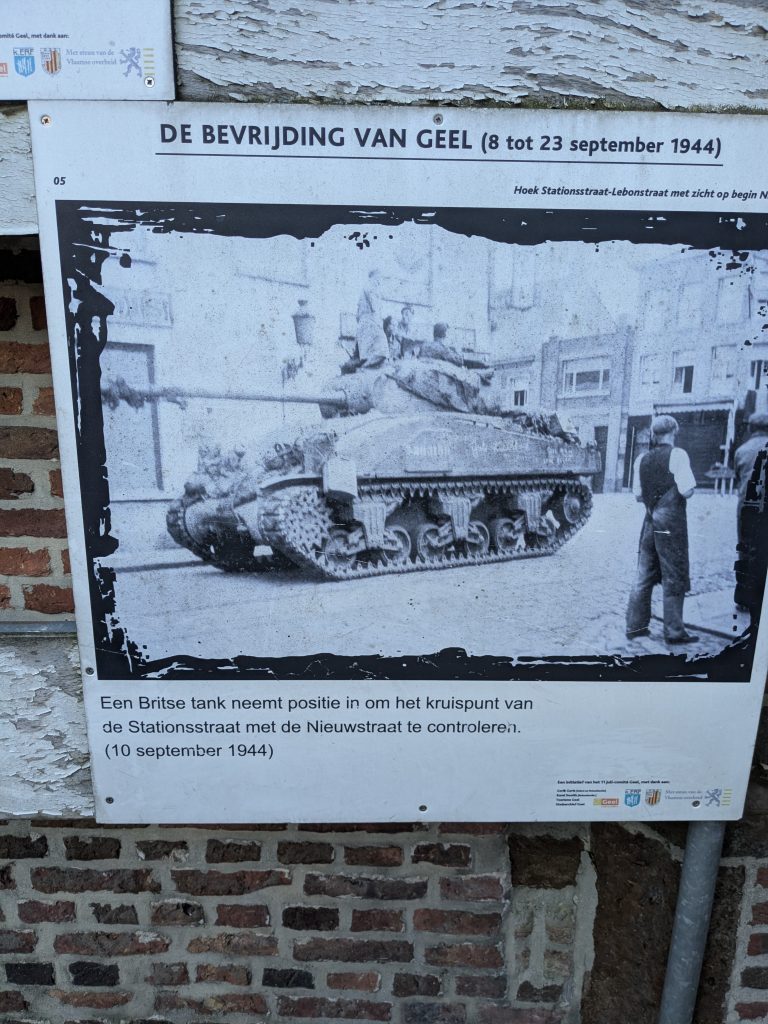

At the start of September 1944, the German army effectively withdrew from most of the Belgian territory that it had occupied and took up a new defensive position behind the Albert Canal which runs just south of Geel.

The Albert Canal is a wide canal. It reminded me of the Manchester Ship Canal. It must have presented quite an obstacle to the British army eager to maintain the momentum that had built up in the liberation of Belgium and the final victory over the Nazi regime.

On 8th September, the 69th Infantry Brigade which was part of the 50th Division of the British army, crossed the Albert Canal under fire from the German army. Included in that brigade were two battalions from the Green Howards regiment. Major Harry Pye commanded one of the companies in one of those battalions. He was killed on the day of the crossing. According to family tradition, he was killed by a sniper’s bullet.

The 69th Brigade and other elements in the 50th Division successfully crossed the canal and occupied the town of Geel. But the German army brought up reinforcements and retook the town so that the British effectively had to take it twice in a battle that raged for a number of days. In total 550 British soldiers died in the battle of Geel along with a similar number of German troops. Around one hundred civilian inhabitants of the town also died.

The Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Geel contains 400 graves laid out in a symmetrical pattern. Each person has an identical gravestone. Families were asked if they wanted anything inscribed on their loved one’s gravestone. Some families asked for very personal things to be written. The family of Private L.D. Brown, who was 20 years old when he died, asked for the words, ‘In memory of our dear Son, A light is gone. A voice we loved is stilled. Mam, Dad and baby sister, Ann.’ Others placed the death of their loved one in a tragic historical context. The family of Lance Corporal H. Norminton asked for these words: ‘He lost his life saving the rest of mankind, as also did his Dad in 1918.’ The gravestone of H Weiss bears a Star of David rather than a cross and includes the information that he served under a false name, presumably to keep his Jewish identity hidden should he be captured by the enemy. His inscription reads, ‘He died for his ideals. Sadly missed by all who knew him.’ One gravestone bears the inscription ‘A victim of the Second World War known only to God.’ Presumably, this body was in such a state that they couldn’t even tell if he was a British soldier. So he may be a German or Belgian civilian buried with the rest. We found Uncle Harry’s grave quite quickly among the rest. His inscription reads, ‘His duty nobly done. In proud and treasured memory.’

The overall effect of the cemetery is one of perfect equality in death but with room for every person to be remembered as an individual. The graves are grouped around a cross with a sword depicted on it and also a large spreading oak tree. The cemetery is carefully maintained. It is a very beautiful and peaceful place.

I wanted to stand in the cemetery and find my great-uncle’s grave and then try and understand the feelings that this experience invoked in me. The first feeling I had was sadness. Great Uncle Harry was a good few years younger than my grandfather. If he had lived, I would probably have got to know him. He would have been part of my childhood at least. Maybe I would have gone to stay with him. I wondered what sort of influence he and his wife, Olive, would have had on my life. And then alongside my personal sense of loss, looking at 399 other graves, I was overwhelmed by a sadness that all these lives had been cut short. So many wonderful things that might have happened, did not happen.

But as well as sadness, I also had a feeling of pride in the victory that Great Uncle Harry had a part in. Before we visited the cemetery, my father and I had got to know the town of Geel. A few years ago, there had clearly been some kind of local history project which had led to pictures from the liberation of the town being displayed around the place, especially near to the churches. The displays were slightly worn but they told the story; the men came and fought and died to liberate us. Not everybody who remembers the death of a family member in war has the privilege to remember them in the context of victory and liberation. I have other great uncles who died as members of the opposing army. Their deaths are remembered in the context not only of defeat, but in the context of a defeat that the world today gives thanks for. Uncle Harry is remembered as a hero in the place where he died.

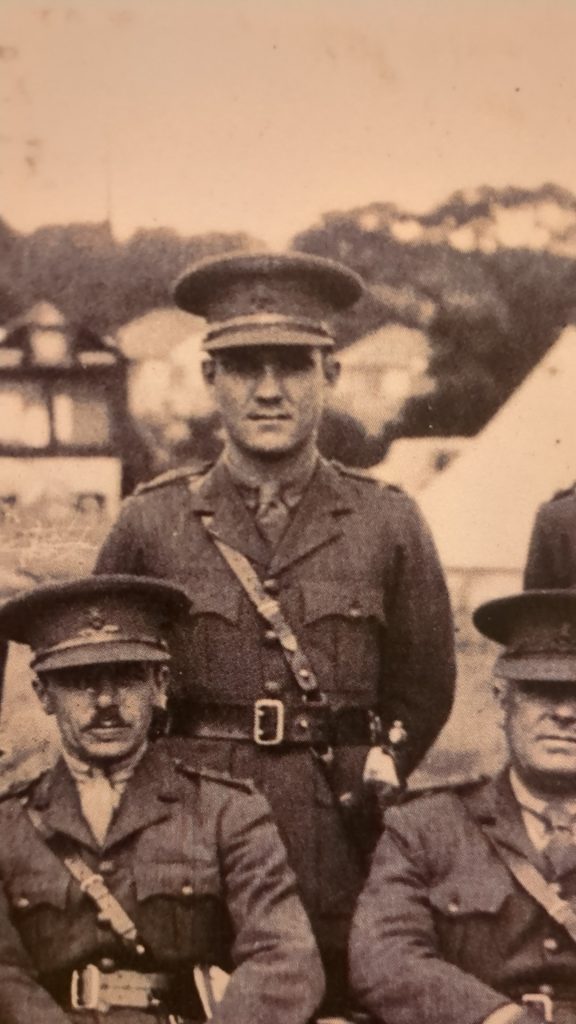

I had done a bit of research into Uncle Harry and thanks to the Staffordshire Regiment Museum I have found out a number of details that have given me pause to reflect. It turns out that Harry Pye went to the grammar school in Stafford and joined the combined cadet force there. He then went to Birmingham Univeristy where he was part of the officer training corps. When he graduated he became a teacher in Eccleshall in Staffordshire, but carried on in the territorial army receiving his first commission in the as an officer in the North Staffordshire Regiment on St Martin’s Day 1933 which friends fo this website will know is 11th November.

Shortly before the outbreak of World War Two, he was attached to a new battalion which prepared to receive recruits from civilian life. We don’t know the details but we imagine he must have played an important role in training men to become soldiers. His battalion was then sent to carry out guard duties in Orkney and Shetland, but somehow, at this point Captain Pye, as he was then, was attached to the Green Howard Regiment which meant that he took part in the ‘D Day’ landings and subsequent campaigns in France and Belgium.

I hope to find out more about how he came to be attached to a different regiment. One possibility is that he volunteered to join a regiment he knew would be involved in the fighting. What we definitely do know is that he made a commitment to join the army and train to be a soldier years before the war broke out and without knowing what sort of war it would be. He didn’t know that he would be in a war that would end in victory. He didn’t know that he would be in a war whose outcome is almost universally regarded as positive today. Without men who were willing to train for war in the early thirties, the British army would have been in no fit state to liberate Belgium in 1944. In this sense, Uncle Harry personifies the most powerful challenge to those of us who are drawn to a pacifist interpretation of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

The Staffordshire Regiment Museum gave me a collection of newspaper clippings about my great uncle. He seems to have been a well-loved teacher. He was active in the local parish church where he married a young woman who lived round the corner. The men in my family are energetic, enterprising, independently minded and resourceful individuals. I imagine that he would have been good at working out how his company were going to get across that canal. I imagine he would have been good at looking after the soldiers under his command. I wondered how many of them he had lost before he himself died.

The Second World War is Britain’s good war. Most British people remember that war as a war our nation was right to fight. And that memory is made simpler by victory. In other parts of the world, some people have to remember wars that may have been right to fight and yet ended in defeat. But the Second World War ended in victory and it was a righteous victory. And the remembrance of it, to a very significant extent, shapes our national identity. It even shapes our remembrance of other wars before and since. Because if we were the good guys in the war that mattered, does that not make us the good guys in all the wars? Already, I can’t imagine Uncle Harry dying in a war that should not have been fought. A man like that wouldn’t do a thing like that, surely?

I think there are three aspects of Britain’s remembrance of the Second World War that are actually problematic for our remembrance culture. The first is the remembrance of a total war, the second is the remembrance of a war that included many serious war crimes and the third is the remembrance of a war that was also an imperialist war. I am going to discuss these problems now and then suggest some possible solutions.

Let us consider first the fact that the Second World War was fought to the death. Hitler’s army executed thousands of soldiers that displayed ‘cowardice’ and he himself committed suicide just as the Soviet Army approached his bunker. For Britian, this was an enemy with whom there could be no negotiation. Only total defeat of this enemy would end this war. Today, Hitler and the Nazis are used in political discourse as a description of total evil, something that has to be totally opposed.

This idea of an enemy that has to be totally opposed and fought until it is utterly destroyed remains alive as a concept in our political discourse today. During the build up to the Iraq War, this idea framed the understanding of Saddam Hussein and his regime across the political establishment in the United States and the United Kingdom. Saddam Hussein was evil and he was a danger and he had to be destroyed a bit like Hitler. The parallel with Hitler was routinely drawn by Paul Wolfowitz who is often described as the ‘architect of the Iraq War’. In the end, the arguments of Wolfowitz and others triumphed over those who argued that on balance the evidence suggested that Saddam Hussein’s power was limited, could be contained and that, while he was an odious dictator, he was only one among many in the world.

One of the legacies of the Second World War is the concept of appeasement. In the run up to the war, politicians in Britain and France tried to seek accommodation with Hitler over Sudetenland. Even the British Legion got involved in some freelance appeasement diplomacy. In the end, the war happened anyway and with hindsight these attempts to keep the peace seemed naïve and mistaken. Today the accusation of appeasement continues to be made, but only in certain conflicts. At the time of writing, any suggestion that the war in Ukraine be brought to an end with a concession of territory to Russia attracts the accusation of appeasement. The argument goes that if ‘the West’ agrees to give Putin the Donbas, he will simply bank that and then attack again in pursuit of more conquests. It is an argument that is based on the assumption that Putin will behave like Hitler. Putin might behave like Hitler in some ways. But it is quite an assumption to make when hundreds of thousands of lives are being lost. We should note that ‘appeasement’ is not used as a concept in many other situations. For example, ‘appeasement’ is rarely if ever used in relation to British policy towards Saudi Arabia and its war in Yemen, the United Arab Emirates and its war in Sudan or Israel and its war in Gaza.

I remember once sharing a bottle of whisky with a group of German school teachers. It was the end of the school year and we were sitting in a garden playing cards. It was in the period just before the second Iraq War. Suddenly, one of the teachers said to me rather accusingly, ‘Why is it that every time there is a war, you Brits want to get involved?’ At the time, the Bundeskanzler Gerhard Schröder was saving his political career by making a very popular stand against Germany getting involved in the war. In my answer I explained this concept of appeasement. A politician can always make the argument in favour of war in Britain, I explained, by drawing a parallel to 1938 when, in retrospect, Britain should have stood up to Hitler but made concessions in the hope that it would maintain peace. It is an idea deeply embedded in our culture that declaring war may well be the least worst option in situations involving a tyrant. For understandable reasons, this phenomenon does not exist to the same extent in German remembrance culture.

Where this phenomenon might impact on our lives again is in a possible build up of tension between Russia and the Baltic states. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania all have a significant Russian speaking minority who do not enjoy the same political rights or economic prosperity as citizens of these countries who speak the majority language. It is really not so unlike the situation with the so-called Sudetenland Germans in 1938. However, the British remembrance culture concept of appeasement might lead the British state away from pre-emptive efforts to build peace in that region and towards an assumption that Britain must be ready to engage militarily to defend the status quo. This might be the next example of how British remembrance culture will directly affect hundreds of thousands if not millions of lives of British people.

Another important aspect of Second World War remembrance is the fact that Britain and her allies committed many war crimes in the pursuit of that war. The irony here is that our modern understanding of what constitutes a war crime flows directly from the development of international law and institutions as a result of this war.

When the British public sees war crimes being committed today, generally speaking these war crimes are condemned for what they are. The obvious recent example is the bombing of Gaza by the Israeli military which has received detailed coverage, especially online. Many thousands of civilians have been killed in a military campaign that claims to be focussed on the liberation of hostages and the killing of their captors. Most British people would, of course, be alarmed if their loved ones where taken hostage and the official response was to bomb the area where they were being held. This has led to widespread condemnation of the Israeli action and the rapid development of public hostility to Israeli actions in Gaza.

The Israeli President, Benjamin Netanyahu, has specifically referenced British bombing of German cities in the Second World War as part of his response to this criticism. The RAF deliberately bombed civilians in pursuit of its war aims in the Second World War. It is an aspect of the British campaign that is sometimes criticised, but overall, within British remembrance culture, the bombing of civilians is praised more than it is condemned. The prime example of this is the film ‘Dambusters’ in which a group of scientists and airmen, sometimes battling with bureaucracy, conceive of a novel way of destroying some dams in order to flood an area and drown thousands of people. The success of the mission makes for a happy ending to the film but in real life it was anything but a happy ending. Thousands of civilians were killed and any of the people who died by drowning were forced labourers brought to Germany by the Nazis.

Netanyahu has also appealed to more recent examples of mass civilian deaths in order to justify the high death toll in Gaza. It is estimated that in the defeat of so-called ISIS, around 250,000 civilians died in the city of Mosul alone. The reason we don’t know precise figures is in itself indicative of a lack of priority given to the whole issue of civilian casualties. Estimates of the number of civilian casualties during the so-called War on Terror, including the fighting in Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria, vary enormously because nobody is really counting them. And so, Netanyahu asks why the outrage when Israel kills tens of thousands when ‘the West’ has killed hundreds of thousands? This assumption that there could be high numbers of civilian deaths in a righteous war is baked into British remembrance culture. Even though the overthrow of fascism in Europe led to a new world order based on universal human rights so that we now have concepts like ‘war crime’ and ‘genocide’, there is very little in British remembrance culture that acts as a brake on such crimes being committed in the future. That is because British remembrance culture has no place for the victims of war crimes committed by British forces in the Second World War.

The third and final issue I want to discuss is the difficulty British remembrance culture has with the fact that, among other things, the Second World War was an imperialist war fought in defence of empire. British remembrance culture sometimes gives the impression that Britain entered the Second World War in order to overthrow fascism and liberate the concentration camps. This is clearly not the case. Much like the First World War, Britain fought the Second World War in order to preserve the balance of power in Europe. But when war broke out in South East Asia, the war also became a war in defence of imperial possessions in Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore, Burma and India. And then at the end of the war the British army, as well as restoring British power in its own colonies, also restored French imperialism in Vietnam and Dutch imperialism in Indonesia, despite the fact that national movements in both those countries had joined the struggle against Japanese imperialism. In Vietnam the British occupying forces actually rearmed Japanese POW’s in order to have them assist in disarming the Vietnamese. In Indonesia, the British occupying army became embroiled in a battle with Indonesian forces in which between 6,000 and 15,000 Indonesians died. The date of that battle (the Battle of Surabaya) is now commemorated in Indonesia as Heroes Day and it takes place on 10th November on the eve of St Martin’s Day.

Charlotte Wiedemann, in her book Der Schmerz der Anderen begreifen (Understanding the Pain of Others), shares an account of VE Day in Algeria. Because de Gaul had promised autonomy for Algeria in return for Algerian Arab support in the struggle against Germany, many Algerians reacted to VE Day as the beginning of the next phase of the life of their nation and came to VE celebrations across Algeria with placards and chants appropriate to this understanding of the occasion. French forces therefore fired on the unarmed civilian demonstrators. The French figure for the number of people killed on VE Day across Algeria is 8,000. But Algerian sources claim a higher figure of around 35,000.

Wiedemann apologises for sharing these figures. She writes that she finds sharing figures of numbers of deaths distasteful as if somebody is compiling a league table of atrocities somewhere. But she makes the point that sometimes we need to hear a figure because the figure is a lot higher than we expected it to be. And when a figure is a lot higher than we expected it to be, we need to reflect that this is because the event that claimed those casualties is simply not as prominent in our remembrance culture as it should be.

Standing the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Geel, I was looking at 400 graves. It would take roughly two more such cemeteries to accommodate all the people British, Germans and locals who died in the battle of Geel that raged for several days. Actually, one cemetery was enough to fill my heart with profound sadness. But even using the most conservative estimates, it would take 15 Geel cemeteries just for the Indonesian dead from the battle of Surabaya and 20 Geel cemeteries for the civilians killed in Algeria on VE Day.

Can we cope this kind of complexity in our remembrance culture? Can we cope with a war that liberated death camps in Europe and re-imposed a doomed European imperialism in South East Asia thereby reigniting another cycle of violence and death? Can something be both good and bad at the same time? Wiedemann concludes that we can. People are capable of holding a number of memories together. We are capable of understanding the pain of others. And does not Jesus tell us that we can do this? And that we must do this?

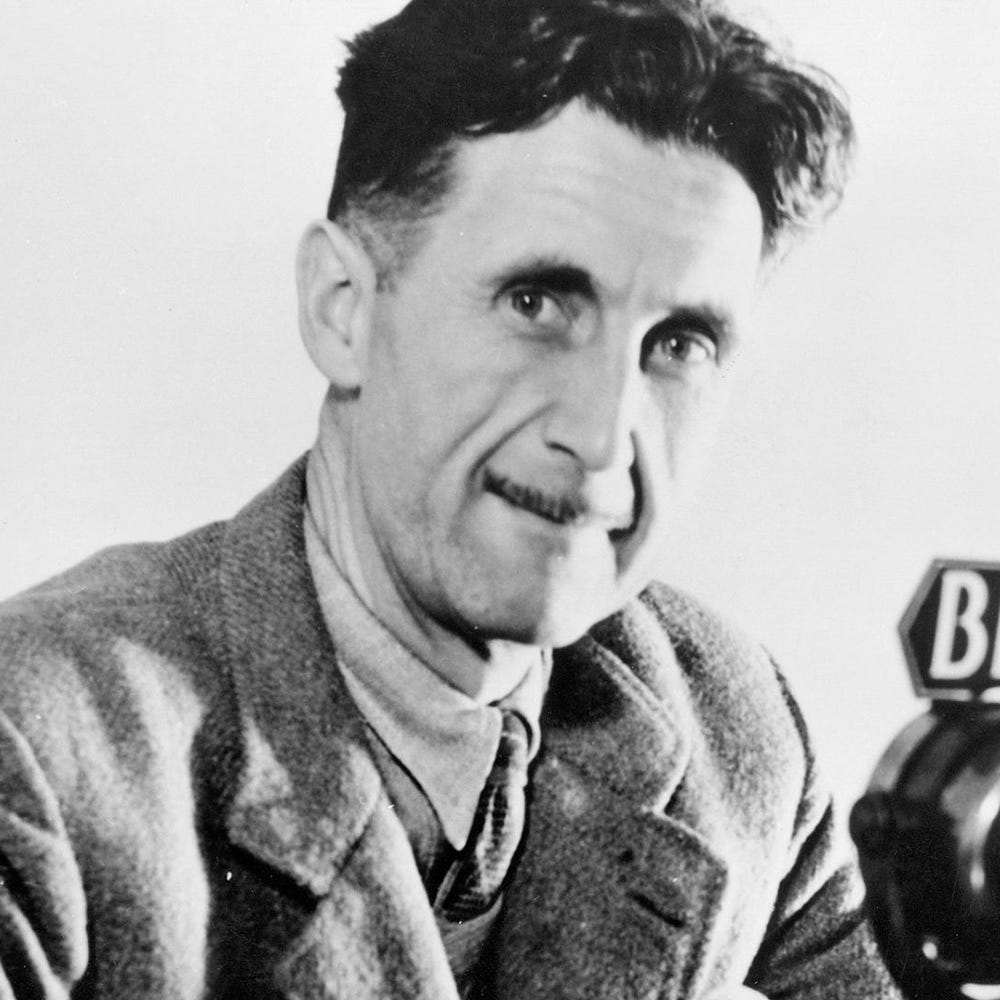

Understanding the many facets of Britain in its efforts to fight the Second World War is the main topic of George Orwell’s famous essay ‘The Lion and the Unicorn’ which has the subtitle ‘Socialism and the English Genius’.

Writing in early 1941, Orwell is arguing for the progressive nature of the British war effort. He is aiming his argument, at least in part, at those members of the Communist Party who were at that time still holding to the line of the Third International that this was a war between imperialist powers in which socialists should remain neutral and focus instead on the class struggle. Orwell, who had risked his life fighting fascism in Spain and had only narrowly escaped death at the hands of Stalinist agents in Barcelona, argued that while the British Empire was obviously imperialist, by declaring war on fascist Germany and Italy, it had embarked on a war that would evolve into an international struggle with fascism, which if victorious, could only have progressive affect all around the world. Even English nationalism, harnessed to an international war effort against fascism, could have a progressive impact.

Orwell proved to be spectacularly correct in his predictions. By mobilising against fascism, the British state had to make the case against fascism and align itself with universal human rights. This then led to the post war transformation of British society with the NHS, housing for all and the expansion of educational opportunities and the scope of the welfare state. One interesting effect of this was that the Royal British Legion, whose membership peaked in 1947, found that all its demands for pensions and housing and medical care for veterans were met by a Labour government who provided these essentials for all working people. Throughout the 1920’s and 1930’s the Legion had campaigned (unsuccessfully) for special treatment for veterans in these aspects of life. After the Second World War, the demands of the Legion on behalf of its members were met in a very short space of time because these rights were won for all citizens.

Internationally, although there was an attempt to restrict the extension of human rights in the French and British empires and in the southern states of the USA, eventually, this effort collapsed under the weight of its own internal contradictions. This means that we now live in a world where people at least aspire to apply universal laws of human rights to all political situations. It is because of the historic participation of the British Empire in the Second World War that the British state can be said to have played its part in the development of this legal system based on internationally and universally applied human rights.

Crucially, this has left its mark on the character of British nationalism itself. At the time of writing, new allegations are being printed in the press about the things that Nigel Farage said and did when he was a teenager. Some of these allegations include Farage’s implied support for Hitler, the Nazis and for the holocaust. These allegations have been difficult for Farage to deal with and he has variously denied them, said it all happened a long time ago and that he had indeed said some silly things but he never said racist things. He has indicated he will not be taking legal action over these allegations and then indicated that he might.

Farage is a politician who stands for the dismantling of the post Second World War welfare state and system of international human rights. His problem with these allegations is that the understanding that Britain fought against the Nazis is so strongly embedded in British remembrance culture that any suggestion that he associated himself with the very same Nazi ideas that the British state fought a world war to destroy will do him great damage amongst his natural voter base. In this respect, we can see that British remembrance culture in its present form can be used to build support for Christian values of valuing each and every human being and caring for our neighbour, via an understanding that as the Second World War progressed, the British state became more committed to the overthrow of fascism and its replacement with a world system based on human-centred values.

While I was visiting Geel with my father, it was our great good fortune to be shown around the church of St Dymphna. St Dymphna is very important to the town of Geel. Her story is that she was a sixth century Irish princess. When her mother died, her father proposed to marry her as his replacement wife. Horrified at this prospect, Dymphna fled to Geel with her chaplain. Her father tracked her down and ordered her execution but the executioner refused to carry out the order for fear of the consequences to his mortal soul and so the father murdered her himself, cutting off her head with a sword. Dymphna was, of course, then welcomed into heaven as a martyr where she intercedes for those who pray in her name.

But her story does not end there. Centuries later some nuns attending to the church where some of her relics were kept found some mentally ill people praying at her shrine. They took them away to care for them and then found that these people, who had been ill for a long time, had made a miraculous recovery. Soon word spread of the efficacy of praying underneath the place where the relics of St Dymphna were kept in her church in Geel and soon people were coming from all over the place so they too could pray and find healing. Pretty soon more people were coming to Geel than the nuns could cope with so they appealed to the citizens of Geel to open their homes to these pilgrims. Thus began an extraordinary centuries-long tradition of mentally ill people coming to Geel, staying in the homes of the citizens and finding healing. Even today, there are over 150 such ‘foster homes’ for people suffering from poor mental health.

Standing in the church of St Dymphna, two things struck me. The first was that St Dymphna is always depicted as a beautiful young woman with a long sword. This is because of the custom of depicting martyrs with the means by which they were martyred. In St Dymphna’s case, she was executed with a sword (by her own father). But the sword reminded me of the sword on the cross at the centre of the Commonwealth Graves Commission cemetery in Geel. I asked of there was a connection. ‘Of course’ came the reply. ‘The sword at the cemetery is the sword of St Dymphna.’

Now I have since discovered that the sword on the cross is a common depiction and can be seen at other Commonwealth Graves Commission cemeteries. According to Adrian Barlow, it was the Church of England, that insisted that a sword be placed on the crosses at the war cemeteries after the first world war in order to draw a parallel between the sacrifice Christ made on the cross and the sacrifice soldiers made in battle. I have long thought that this parallel is difficult to sustain because the soldiers who died in battler also killed other people, whereas Jesus (and indeed St Dymphna) didn’t kill anybody. Nevertheless, I found the local interpretation of the sword in the light of the story of St Dymphna, revealing.

I said that two things occurred to me and the other thought came as I stood next to the place where the relics of St Dymphna are stored. The tradition is that people go under the relics on their knees to pray to St Dymphna nine days in succession in the hope of finding healing. I suddenly thought of the veterans and other people I know who are traumatised by war and cut off from their communities because of their military service. It struck me that my pastoral ministry to these people is to assure them of God’s love for them – to assure them that they are not cut off. I don’t really counsel them because I don’t have those skills. Rather, I express my own faith that they will be healed. Is this not very similar to the nuns of St Dymphna who have, over the years, said to people seeking healing, let us pray together every day and we shall be healed. And this faith tradition has yielded results over the centuries, essentially by sharing faith in the love of God.

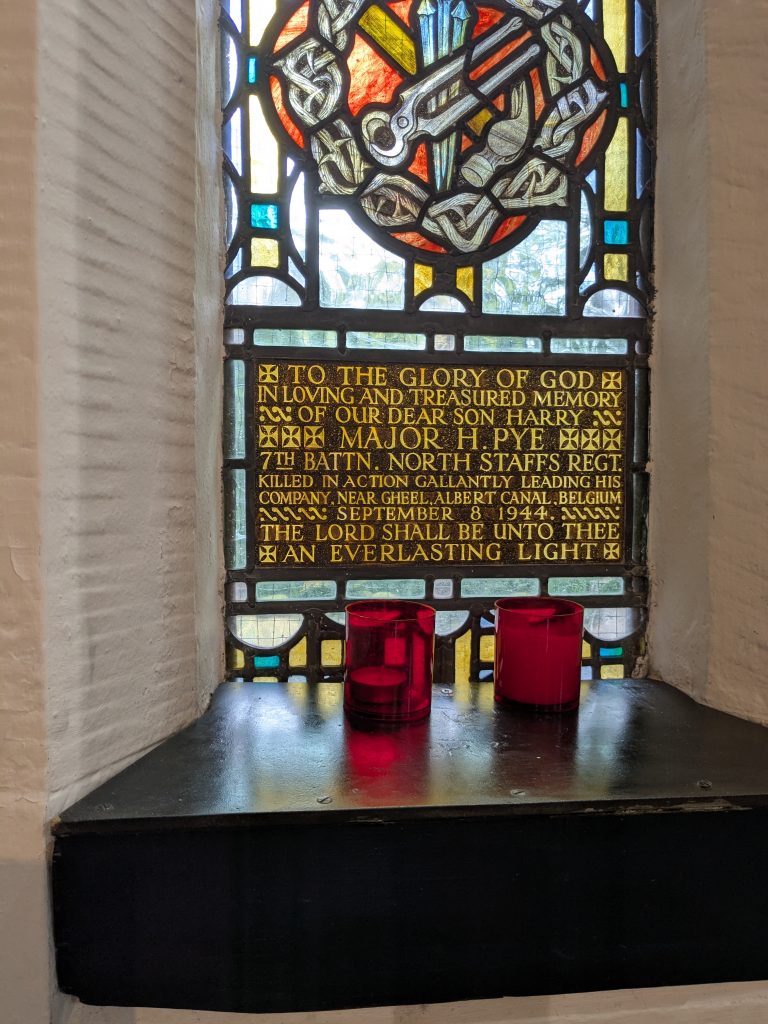

Before my trip to Belgium, I visited the church that my great uncle and his parents worshipped in – St Thomas, Berkswich near Stafford. After the war, my great grandparents paid for a small stained glass window to commemorate my great uncle in this church. The window reads, ‘In loving and treasured memory of our dear son, Harry … killed in action gallantly leading his company near Gheel, Albert Canal, Belgium.’ And then underneath it reads ‘The Lord shall be unto thee an everlasting light.’

It struck me that the words my great grandparents chose absolutely embrace the emotions they felt at the loss of their son. And in the words they chose to explain how he died they recognise also the sense of duty that he himself embraced that led to his death. Nothing here is avoided. Everything has been said. And then comes the quote from Isaiah with its image of the Kingdom of Heaven in which all our light will come from God himself.

If you sit in the pew next to Major H Pye’s window (as I did when I went to worship at the church) you have a great view of the altar where Harry Pye would have assisted at the Eucharist in commemoration of the sacrifice that Jesus made on the cross for the liberation of all humanity from oppression, sin and death.

Harry Pye, in his life and in his death, probably came as close as you can possibly come to a Christian martyr whilst bearing arms. He was as pure a war hero as it is possible to be. For years he prepared himself for war. And when war came, he was thrown into a battle which was as close to being a perfect battle for liberation from evil as we can possibly imagine. He led a company in the front line of battle. He would have lost soldiers who were under his command, and he would have directed their efforts to kill the enemy. We know today, as he would have known, that the sacrifice he made whilst bearing arms is not the same sacrifice that Jesus made on the cross or even St Dymphna made in Geel centuries before he ever arrived at that place. His sacrifice was not the same or equivalent to theirs. And yet because of their sacrifice, Harry Pye and those who mourned him, were and are able to draw near to God, confident that they would and will find comfort and healing and live for ever in his everlasting light.

It is for this reason that I believe that Remembrance Sunday in church should have the eucharist at its heart. The question arises, however, having remembered Christ’s sacrifice on the cross and its liberating impact on the world, how are those who share in his supper to live his risen life in the world today. What do we stand for? By what values do we live our lives and build our nations? These are questions I will turn to in a future blog.

A tour de force, Robin. Congratulations.

A bit of criticism which is intended to be constructive: I am not convinced that there is a ‘British remembrance culture concept of appeasement’ and a ‘British remembrance culture’ – both terms that you use – which have the strong influence on attitudes to appeasement that you describe. Where and how do ‘history’ and ‘memory’ and ‘remembrance’ meet, intersect and overlap? How does ‘remembrance’ differ from ‘history’ and ‘memory’? Is ‘remembrance’ the same as what happens on Remembrance Sunday?

You are well-qualified to offer an alternative to the inherited tradition and ritual of Remembrance Sunday.