Let us now sing the praises of famous men, our ancestors in their generations.

Some of them have left behind a name, so that others declare their praise.

But of others there is no memory; they have perished as though they had never existed;

they have become as though they had never been born, they and their children after them.

But these also were godly men, whose righteous deeds have not been forgotten;

their wealth will remain with their descendants, and their inheritance with their children’s children.

Their descendants stand by the covenants; their children also, for their sake.

Their offspring will continue for ever, and their glory will never be blotted out.

Their bodies are buried in peace, but their name lives on generation after generation.

(Or in the old translation: “Their name liveth for evermore”)

Sirach 44: 1, 2-14

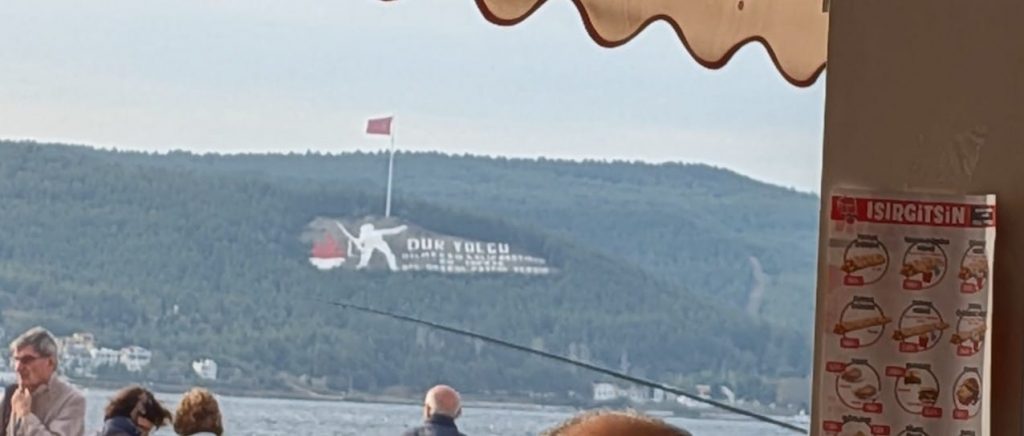

If you take the ferry across the Dardanelles at Çanakkale you cannot fail to notice a slogan that has been written in huge white letters on the hillside. The slogan reads (in Turkish), ‘Stop traveller! Maybe you didn’t know! It was on this soil that an epoch came to an end!’ You see that and you realise that this isn’t going to be just another sightseeing trip.

The Dardanelles is a narrow body of water that opens out into the Sea of Marmara. At the other end of the Sea of Marmara is an even narrower body of water, the Bosphorus, that takes you past Istanbul and out into Black Sea and the only warm water ports the Russian Empire had in 1914 on the European side of the world.

In 1915, British and French naval ships attempted to force the Dardanelles. Their aim was to get their fleet into the Sea of Marmara, bombard Istanbul and knock the Ottoman Empire out of the First World War paving the way to a Russian annexation of Istanbul and neighbouring regions. This naval expedition was defeated by Turkish artillery and Turkish mines laid by Ottoman troops partly led by German officers.

Unwilling to give up, the British and French then landed troops on the Gallipoli peninsula which is a long narrow and mountainous peninsula on the far side of the Dardanelles from the town of Çanakkale. The plan was to attack the Turkish artillery from behind so that the ships could pass through the straits. But the Turks were alive to the danger and had troops in position to defend the peninsula. They were able to prevent the British and French advancing much beyond their beachheads and after several months of bloody trench warfare, the armies of the British and French empires withdrew, having achieved none of their objectives.

Today the peninsula is a national park, covered with cemeteries, memorials, museums and re-constructed trenches. You can go round and visit some of these on your own if you have your own car. Or you can book on a tour, which is what we did.

I thought the ferry journey would be a peaceful time when we could collect our thoughts, but things turned out very differently. We were discovered on the ferry by three coachloads of 14-year-olds from Gaziantep, in southeastern Turkey, who were delighted to meet some real live foreigners and they gathered around us and practised their English language skills by bombarding us with questions which my wife and I endeavoured to answer. I was struck that so many of their questions were about identity. Manchester City or Manchester United? Ronaldo or Messi? What is your favourite animal? And then we got onto selfies and one girl asked us to make the Turkish nationalist grey wolf sign with our fingers. As we got off the ferry I wondered if we would bump into them again.

Coming off the ferry, we met our tour guide who was called TJ. He is a Turkish Australian dual citizen and has been guiding visitors to Gallipoli for many years. We gathered in his guesthouse with the other members of our tour who were all Australian and then we set off to Anzac Cove.

Anzac Cove is a beautiful place. It is stunning, actually. It feels very spiritual – on eo those thin places where God seems close to you. TJ was a very good guide. He didn’t rush us. He didn’t overburden us with facts and stories but rather he told us just enough. He let the place do its work on us.

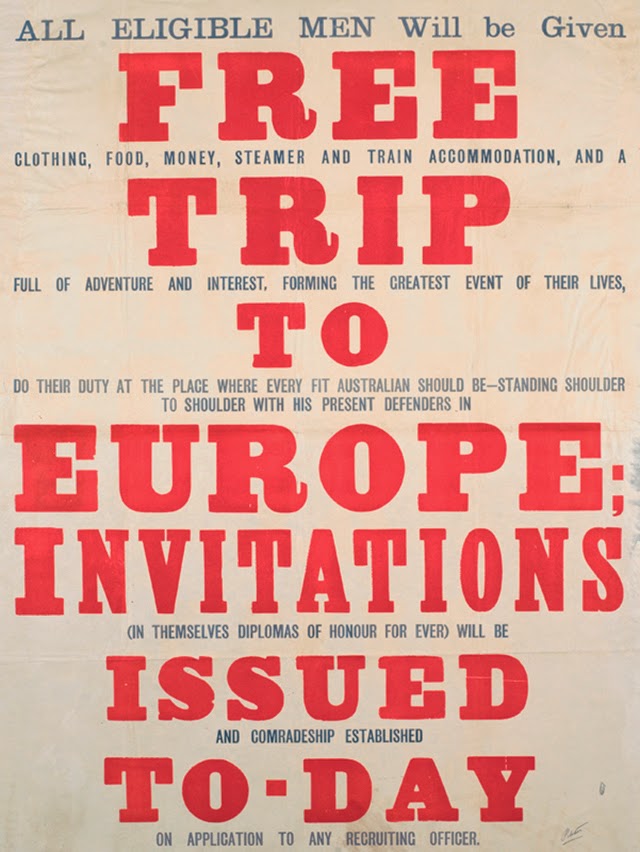

He told us about how the Australian soldiers were recruited with promises that they would see the world and visit Europe. He pointed out that a significant number of them gave false names when they enlisted, suggesting that they were running away from something. He explained that access to the battleground to bury the dead was one of the articles in the armistice the British effectively imposed on the Turks in 1918 so that burial parties returned to Gallipoli three years after the battle ended to erect gravestones on graves previously marked with crude wooden crosses and to bury any remaining unburied bodies identifying them where possible. Usually, this was not possible.

Families were contacted when gravestones were erected and asked if they wanted any additional words carved on the stone. They had to pay per word. As a result, some graves have additional inscriptions and others do not. And the inscriptions vary so that across the whole cemetery you see a broad range of expressions of grief so that the overall effect feels very deep and nuanced.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s editorial contribution is a very short and factual description of the battle in English and in Turkish and the words, ‘Their name liveth for evermore’ which I discovered afterwards comes from the Book of Sirach in the Apocrypha and I have quoted the passage it comes from in a more modern translation at the top of the blog.

And then we moved on to the next cemetery and the next memorial and so on until we had completed what was essentially the Australian and New Zealand tour of the battlefields. All in all, it was a lot of work to erect these cemeteries and monuments. I wondered whether 1918 was the first time the British Empire went to this sort of trouble to bury its dead.

Later, I would discover, that the opportunity to memorialise their war dead was not extended to the Greek government who sent an army to invade Anatolia in 1919 and were then defeated. Touring the cemeteries and monuments around Bozüyük in Anatolia, I asked our taxi driver whether there were any cemeteries for the Greeks like the cemeteries we had seen at Gallipoli for the Australians. He smiled a slightly embarrassed smile and said, ‘The things is, we don’t really like the Greeks.’

But back to Gallipoli: TJ asked us whether we would mind also going to the Turkish cemetery and monuments. That’s where the toilets are, he explained. Our group was happy to go to the Turkish cemetery. And it was at one of these sites (and there are many) that we saw the teenagers from Gaziantep going about their tour. Seeing them brought into sharp focus that there were two parallel narratives running side by side on the Gallipoli peninsula. We had been on our tour. They were on theirs.

The Turkish narrative told at Gallipoli was very strong. We were attacked. We defended our country against invaders. We repelled the invaders through the courage of our soldiers and the courage and leadership of Mustafa Kemal (who would later be called Atatürk, ‘Father of the Turks’.) And now we are a happy and confident nation. In the museum there was a place where you could put up post-it notes to say how you felt and what you had learned. Judging by the handwriting, it was mainly young Turkish people who took up this offer. They expressed their gratitude to the martyrs who had died for their country and said they would pray for their souls.

I thought about the slogan you see on the side of the hill overlooking the Dardanelles. An epoch ended here. The epoch of the Ottoman Empire as the sick man of Europe constantly giving ground. This was the epoch that ended. After the Battle of Gallipoli, the Turkish nation discovered the strength and confidence to defend its land and build a nation. A new epoch began. This is the narrative you see in the Turkish parts of Gallipoli and it is reinforced in memorials and museums and in the names of schools and streets across the country.

All the little details that might complicate this narrative were downplayed or entirely absent. You have to look very hard to find any evidence that some of the Ottoman soldiers who died at Gallipoli were not in fact Turkish but were recruited from across the polyglot Ottoman Empire. Neither was the fact that most of the people living on the Gallipoli peninsula in 1915 were actually Greek speaking, mentioned anywhere that I saw. There was very little to be seen about the German officers who were actually in command and played a critical role. Or of the Ottoman war aims in World War I, which included reconquest of the largely Greek speaking Ionian islands and areas of the Caucasus held by Russia and populated by Armenians, Georgians and Kurds as well as Turks.

All these complicating factors would make the narrative more difficult to grasp and more difficult to digest. Turkey is a nation built around a strong and robust narrative personified by Atatürk himself. There is one major fissure running through that narrative; a split between Islamist and secular interpretations of the national narrative. That gives Turks enough to argue over without making this any more complicated.

But I was on the Australian tour not the Turkish tour. Was there a national Australian narrative? And if so, what was it?

The closest that I came to such a thing was a document left at Lone Pine Memorial by the ‘Spirit of Anzac Prize recipients 2025’. Their statement signed with 12 names ends like this,

‘Though separated by distance from home, your unyielding bravery in the face of adversity continues to resonate, inspiring us all with a profound sense of duty and unity. Today we honour not just your contribution to Australia’s history, but the enduring values of resilience, mateship and selflessness that you embodied and which continue to shape our future. Lest we forget.’

It is similar to the Turkish narrative but not nearly as convincing because it is trying to make sense of the deaths of soldiers who were defeated. Who didn’t die defending their country but invading somebody else’s.

Afterwards I tried to find out more about the Spirit of Anzac prize. This is from the Victoria State website:

‘The Premier’s Spirit of Anzac Prize is an incredible chance for young Victorians in years 9 to 12 to explore Australia’s wartime history and honour those who have served’.

Essentially, the prize is a free trip to Gallipoli. I thought of the recruitment posters TJ had shown us offering young men ‘a chance’ to see Europe. The website goes on to talk about strengthening links between young people and the Australian armed forces, which feels like an aspect of remembrance for another blog.

I was also able, of course to talk to the other people on my tour who were all Australian. What they said was rather different to the statement from the Spirit of Anzac Prize recipients. They told me about the dawn Anzac Day tradition they had known all their lives. The emotions they described to me were along the lines of what a terrible waste of life, what a tragedy, how brave they were… and a little bit of how the arrogant British officers made the Australian soldiers fight their battles for them, a theme I seem to remember from the Gallipoli film starring Mel Gibson. I must watch that film again…

To be honest, by the end of the tour, my feeling was why did the British Empire soldiers come here? They came from Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, India, Sri Lanka and Nepal, as well as from Britain. They came to somebody else’s country to fight to expand an Empire that few of them even had any material stake in. We have to remember that Iraq, Jordan and Palestine were added to the British at the end of the war to go with other possessions: Egypt, Cyprus and Kuwait which had recently been acquired because this was a rapidly expanding empire. The cause these men died for was the expansion of that empire and they killed thousands and thousands of people whose graves are just over the way from their own. What an earth were they fighting for? That was my personal narrative. Among other emotions, I was feeling anger as the tour came to an end.

But not just anger.

There was something very powerful in seeing the two remembrance traditions weaving their narratives effectively in the same space. At one spot you could see the memorials at the same battle site with Turks looking at one memorial while Australians looked at the other. And there was one place where the narratives met in a most decisive fashion.

Apparently, there was a moment in one of the battles when an English captain lay wounded in no man’s land crying out in pain while the battle raged on with soldiers firing at each other from their trenches. Then one of the Ottoman soldiers raised a white cloth in the air. The Australians stopped firing and the Ottoman soldier then got out of his trench, walked across to where the English captain lay, picked him and brought him to the Australian lines, laid him down, turned his back and walked back to his own lines. And the whole time nobody fired a shot. Until he was safely back in his own trench.

Many have suspected that this story is made up. But it might be a true story. Our guide, TJ, claims to have met the grandson of this English captain who confirmed the story was true. The Australians on our tour said they had never heard this story (and they knew a lot about the battle of Gallipoli). TJ pointed out that the story was consistent with many soldiers’ accounts of the two sides sharing food and tobacco with each other and written accounts which show that the Australians developed a lot of respect for their Turkish opponents. Not enough respect to stop shooting them at the time. But maybe enough respect not to go shooting them again?

Something else. In 1934 the first official group of grieving relatives from Australia and New Zealand, mainly mothers, came to visit the place where their loved ones were buried. And Atatürk met them and gave a speech. An excerpt from the speech is displayed on a large memorial in Anzac Bay and, I must admit, it made me well up slightly when I saw it even though I had read these words before.

“Those heroes who shed their blood and lost their lives…You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore, rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here, in this country of ours…You, the mothers, who sent your sons from faraway countries; wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well.”

It is actually, a very unusual thing to have the dead from two opposing armies so carefully and caringly commemorated where they once fought each other. The British army had never taken such care over its dead before but at the end of the First World War, with the threat of revolution very real, there was a need to respond appropriately to the enormous grief that gripped British and Commonwealth society. As victors in the war (although not in the battle) they were able to insist on gathering their dead and burying them. And a few years later, the new government of Turkey was constructing its own robust national narrative for a new epoch and was prepared to bring remembrance of former enemy soldiers into this narrative.

Just bringing two remembrance cultures into one geographical place like this is as powerful as it is unusual. And it prompts a range of responses from any thinking visitor. I commend Gallipoli as a place to visit to anybody who is interested in humanity and what God has in store for it.

One of my initial responses to visiting Gallipoli was my response to the words from Sirach which are written on a monument at every Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery.

“Their name liveth for evermore”

I wondered if that is all that needs to be said. Tempting as it is to try and impose a narrative on what you see in Gallipoli and try and relate it to some idea you have of what it means to be Australian or what it means to be able to say you are a Turk, I wondered whether actually all that we are being called to do here is to remember those who had their lives cut short; those who came from the mountains of Nepal, the plains of the Punjab, the shores of South Island and Newfoundland or the streets of Sydney and Lancashire, and also the villages of Anatolia or the bazaars of Aleppo and share in a collective memory of them so as to ensure that these lives, so casually thrown away, are not forgotten.

Is this a safe place where the world can meet today? Isn’t this the place that Atatürk welcomed the grieving mothers to, who came from faraway lands?

And thinking about this from a church perspective; isn’t this the safe place where we can meet with God, who knows all our grief and wipes away every tear? Is this the place that the church should gather people on Remembrance Sunday? Should we gather and read Sirach 14?

But a few days passed by, and I began to change my mind. As I continued my travels through Turkey, I encountered again and again the same national narrative that just about holds this country together. It is a robust narrative, not because it is entirely watertight in terms of historical accuracy, but because it serves a purpose and it has worked for just over one hundred years. We came together as a nation. We were brave. We had faith in ourselves. We gave up pretentions of empire. We stand for peace at home and peace in the world. Happy is he who can say, I am a Turk. This is the narrative that Atatürk personifies and walking around Turkey you are reminded of it, and this is no exaggeration at least in an urban setting, you are reminded of it every minute, in the names of streets, the flags, the ubiquitous pictures and statues of Atatürk.

Maybe a nation needs a narrative. One that is robust and, of necessity, oversimplified. One that talks about the past so as to make sense of the present and set out a vision for the future.

If a nation needs a narrative and the church draws back from articulating one, then are we just leaving the field clear to narratives that will lead us to disaster?

So, a future blog will consider this. What is the national narrative that the Church of England offers to the nation its serves?