For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven:

a time to be born, and a time to die;

a time to plant, and a time to pluck up what is planted;

a time to kill, and a time to heal;

a time to break down, and a time to build up;

a time to weep, and a time to laugh;

a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

a time to throw away stones, and a time to gather stones together;

a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

a time to seek, and a time to lose;

a time to keep, and a time to throw away;

a time to tear, and a time to sew;

a time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

a time to love, and a time to hate;

a time for war, and a time for peace.

I know that whatever God does endures for ever; nothing can be added to it, nor anything taken from it; God has done this, so that all should stand in awe before him. That which is, already has been; that which is to be, already is; and God seeks out what has gone by.

Ecclesiastes 3: 1-8, 14-15

This famous passage from Ecclesiastes describes the human struggle to find truth and consistency. When we reflect on our past, we search for eternal truths that will guide us into the future for ever. The writer of Ecclesiastes is saying that this search is ultimately futile.

But there is such a thing as truth. It is a truth, as Miroslav Volf writes, underwritten by an all-knowing God. God knows everything that has happened and everything that will happen. Those in search of truth ultimately find their way to him and, in him, their journey ends.

That does not mean that we should not search for truth. The search for truth is an essential human activity and we are called to engage in it. To those who engage in the search for truth, it will seem like an unending journey, as we discover, reflect, refine and move forward. But to the God who knows everything, it is the process by which creation moves towards its final fruition.

This essay looks at some local examples of remembrance; attempts to make sense of the past, to capture it and preserve it as a guide to future generations. It explores the limitations of human attempts at remembrance and also its potential to bring us nearer to God.

The small village of Zündorf on the river Rhine offers the citizens of nearby Cologne a pleasant destination for a family excursion. There is a small, wooded island in the river that you can access by a bridge for a pleasant walk and a number of inviting cafes and an ice cream parlour cluster around a small square. Zündorf is also on the Rhine long distance cycle path and in the summer, there are quite a few cycling tourists passing through who take the opportunity for a short break and some refreshments.

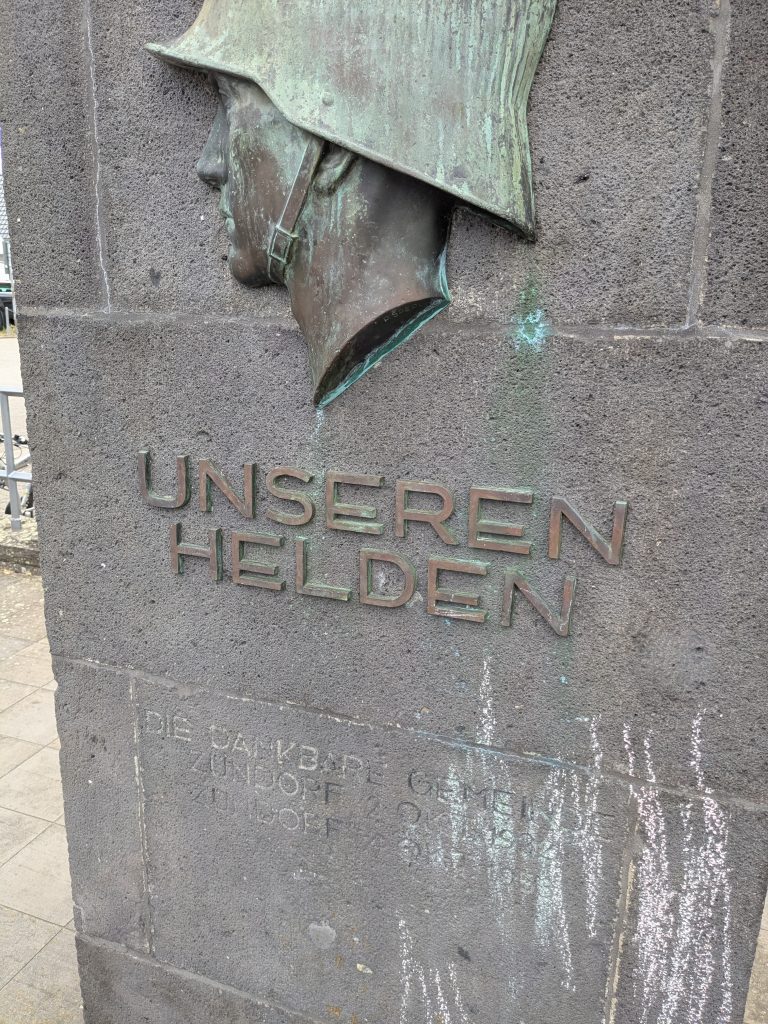

Many of them must surely notice the war memorial in the main square. It is rather tall and prominently located and the visitor’s eye is drawn first of all to the bas relief of the head of a German soldier wearing one of those familiar shaped helmets they wore towards the end of the First World War and during the Second World War and underneath, in large letters, are written the words, ‘Unseren Helden’ (which translates as ‘Our Heroes’).

A monument like that merits a closer look, and when you do look more closely you see the names of soldiers from Zündorf who died in the two world wars arranged on the monument by the year of their death. In addition, there are the three names of soldiers who died in the three shorter Bismarck wars on 1864, 1867 and 1870. And then you will make out, underneath where it says ‘Our Heroes’ the words ‘The grateful community Zündorf October 1932’ and then underneath that, ‘Zündorf October 1953’.

This type of expression of communal gratitude to heroes who gave their lives is an emotion with which we are very familiar in British remembrance culture. But there are a number of things about this monument that seem strange to British eyes.

First of all, the monument is not in especially good condition, and this is contrast to the state of the rest of Zündorf which is generally in very condition. So, while the monument is very prominent, you don’t get a sense that it is being carefully maintained. You feel it stands in the main square slightly sheepishly. And yet it is still there.

The second odd thing is that this expression of gratitude is made to heroes who, not to put too fine a point on it, lost. These are heroes who died without achieving their war aims and so one wonders what the community is saying it is grateful for. In Britain, the heroes whose names are listed on the memorials can be said to have won a victory. Didn’t these heroes die for nothing?

The third thing that feels odd is, (and again, how can I put this?), looking at the familiar shape of the helmet which we recognise from so many war films, aren’t these heroes in fact villains? Didn’t millions of people die at the hands of these so-called heroes?

As it happens, Zündorf, had a thriving Jewish community for at least two hundred years and, until 1938 at least, it had its own synagogue. Some of the Jewish inhabitants of Zündorf would have been killed in the Nazi genocide which was carried across Europe by soldiers wearing those helmets. Are we really calling them heroes today?

And finally, the date when the monument was first erected. 1932. Over 14 years after the end of the First World War. Why the delay? And why was the memorial erected then? Why not earlier, when the pain of loss was fresher in the minds of the community of Zündorf? War memorials in Britain were generally erected in the early 1920’s.

One possible reason is that Zündorf was part of the zone occupied by allied forces after the First World War until 1926. There may have been limited scope before then for the erection of war memorials. Another factor may well have been the political situation in 1932. While the Nazi party was gaining strength across Germany, in the Cologne area, the strongest party was the Zentrum Party, a kind of centrist pro-capitalist Catholic party. But their closest challengers came from the right. Was this why they adopted the language of gratitude for heroes? Was this an exercise in saying to the many bereaved people of Zündorf – your boys were heroes, we are all grateful, stick with us and ignore the more extreme nationalism of the Nazis?

Because the weight of grief cannot be denied. The list of the fallen is a long list for a small community. The desire to say that they were not forgotten, that they will always be remembered, would have been overwhelming. It is an instinct with which we are familiar in Britain. British soldiers fought in the same wars, after all.

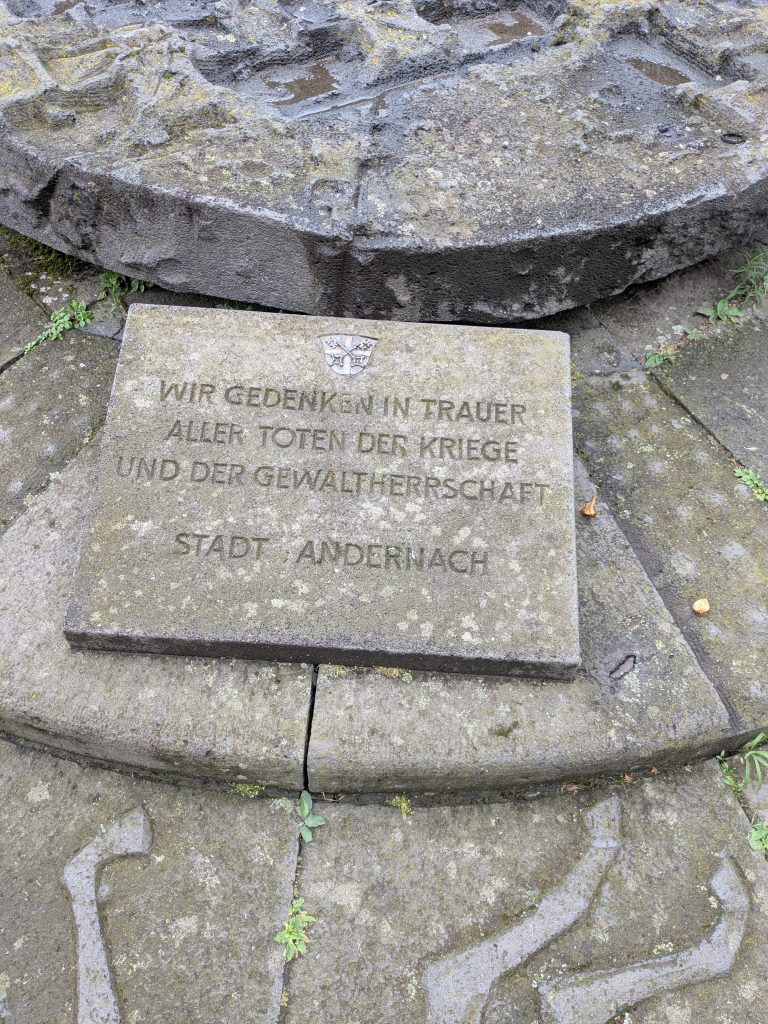

The early 30’s seems to have been the time for war memorials. Just 50km up the Rhine is the small town of Andernach. There, on the site of some 17th century fortifications overlooking the Rhine, a Memorial Union formed in 1928 and led by a Professor Heinrich Aschenberg, erected a monument in 1930 ‘in honour of our fallen heroes; they died so the Rhine would remain German.’

Again, you have to remind yourself that these heroes lost their war. Andernach, along with Zündorf and the rest of the Rhineland, was also occupied after the First World War so, in fact, for a number of years the Rhine was not entirely German. These heroes died and the foreigners got the Rhine anyway, at least for a while. But by 1928, the Rhine was being handed back to Germany and it seems Professor Aschenberg wanted to link this in people’s minds to the men who had lost their lives.

The wider context here is that the history of a French threat to the German communities along the Rhine was a long one. Towards the end of the seventeenth century, the armies of Louis XIV waged what was essentially a genocidal war along the Rhine which included an assault on Andernach and there was a significant depopulation of the whole area. By then he had already taken the German speaking lands of Alsace and Lorraine into his kingdom. And the French came back in 1798 and absorbed Andernach into France proper until 1814, so for almost a generation. Fear of French aggression was very real in Andernach and the idea of keeping the Rhine German was absolutely critical to the identity of this community. Aschenberg knew what he was about.

Thinking again about the Zündorf memorial, one wonders what the thought process was in 1953? Obviously, many families in Zündorf were grieving for soldiers who had died in the Second World War. Once again the feeling that something should be done to remember them must have been overwhelming. Maybe, simply adding the new names to the old memorial, was the easiest and cheapest solution? 1953 wasn’t a time for collective reflection on what had happened during the Nazi period – this came much later in the sixties and seventies. 1953 was a time to get things sorted and crack on. And so, the names of the fallen from the last war were added to the memorial. They were heroes too and the community was grateful to them as well. And now it’s set in stone and all the people who come to Zündorf can buy an ice cream and wonder at the community which is grateful to the heroes of Hitler’s army.

Maybe it’s because monuments are made out of stone that we think of them as timeless and eternal. Whereas, in fact, they are of a certain time and, while they may aspire to offer a message to last through the ages, in fact the words chosen in one particular time may carry increasingly different connotations for successive generations.

The monuments in Zündorf and Andernach are, of course, purely civic monuments without any religious imagery. Does it make a difference when remembrance monuments are placed in religious places of worship? Is it possible in a religious context to come up with a memorial that will stand the test of time? Do memorials in religious contexts benefit from reaching out to the all-knowing God who underwrites the truth of the world?

In the cathedral of Downpatrick in Northern Ireland, there is a remembrance window for the soldiers of all ranks of the Fifth Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles (the Royal South Down). It depicts angels adjusting the helmet of a soldier in full armour with the words ‘put on the whole armour of God’ Underneath you can read the words, ‘I have fought a good fight. I have kept the faith. Be thou faithful until death and I will give thee a crown of life.’ And to illustrate this a large angel (maybe St Michael?) is pointing heavenwards.

The words of the first sentence come directly from St Paul’s letter to the Ephesians. Their use in this context is rather strange because when Paul talked about armour, he was not talking about putting on real armour. Rather, he was using armour as a metaphor which he later spells out; ‘Stand therefore and fasten the belt of truth around your waist, and put on the breastplate of righteousness. As shoes for your feet put on whatever will make you ready to proclaim the gospel of peace. With all of these take the shield of faith with which you will be able to quench all the flaming arrows of the evil one. Take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God.’ (Ephesians 6: 14-17)

But if the words of the first sentence are being quoted out of context, then the second sentence on the window is an astonishing act of violence against Scripture, because it is a bolting together of the first half of a sentence from the Book of Revelation and the second half of a sentence from the second letter to Timothy. This is done to come up with an entirely new verse designed to serve an entirely new purpose. These are holy warriors who are receiving their reward in heaven. It is a holy war we have been fighting.

One wonders what the thought processes were that led to this window design? It must have been a very special and emotional moment when the local regiment chose to bring its remembrance to the cathedral. The pain of bereavement and grief must have been omnipresent in that community at that time. How did the cathedral fail to find words and images from actual Scripture to speak into this situation? Why did they have to misrepresent and butcher Scripture in this way? And as later generations look at this window, what are we meant to think?

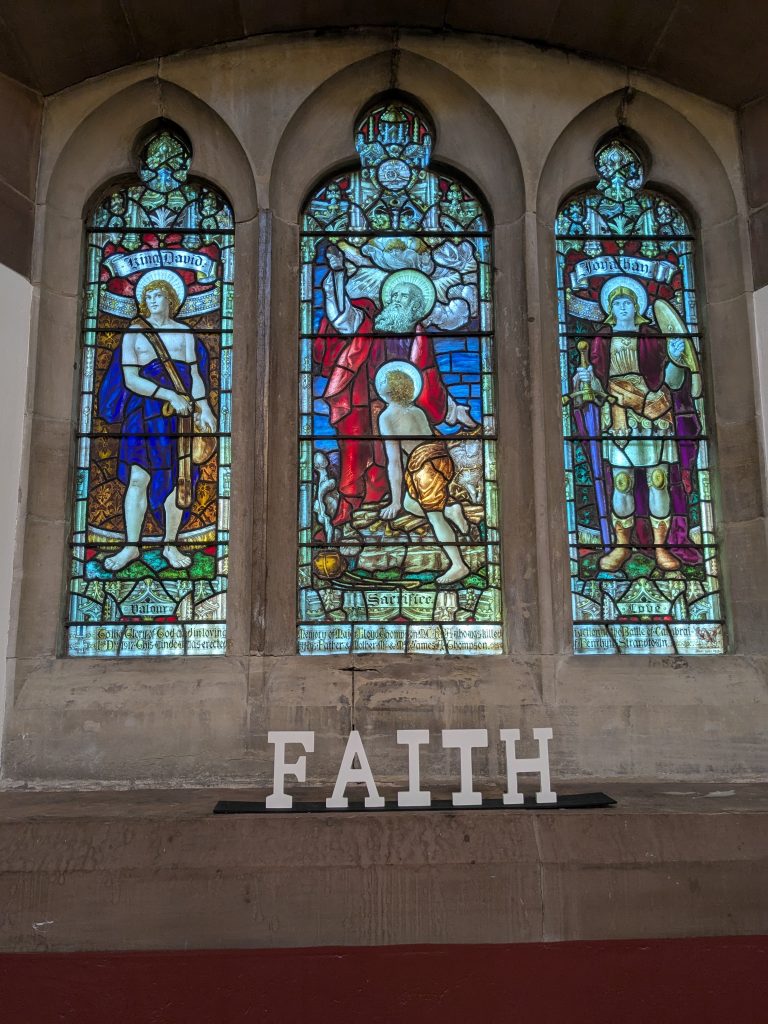

The church of St Mark Dundela in Belfast is graced with a number of beautiful stained-glass windows. The church was originally built with unadorned windows but following a significant legacy a glorious window was installed behind the main altar which included, unusually, a depiction of Martha and Mary and the Samaritan woman whom Jesus encountered by the well. Until the end of the First World War, this would have been the only stained-glass window in the church. It would have made a dramatic impact on worshippers in that church.

After the First World War, it was decided to install a stained-glass window in the baptistry as an act of remembrance for those who had died in that war. This new window would face the large window behind the altar.

There are actually two main remembrance windows but they are conceived as a pair. Across the top of both windows we see four Old Testament warriors; Joshua, Gideon, David and Juda Maccabeus. (Actually, Judas Maccabeus is technically a warrior from the Apocrypha).

Underneath these four there are four Christian Saints; Patrick, Columba, George and David, each representing one of the four home nations of the United Kingdom, England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

The words underneath are an entire verse, so not something bolted together. ‘Their seed shall remain forever. Their bodies are buried in peace. Their glory shall not be blotted out, but their name liveth for ever more’. The verse comes from Ecclesiasticus 44:13 so also from the Apocrypha.

The warriors are there as the Biblical antecedents of the soldiers who died. It is interesting that they are present in this window and Jesus Christ is not. And the four saints must surely symbolise the union for which they died bearing in mind that this window was commissioned at a time of significant upheaval in Ireland. It was around this time that the Republic of Ireland came into being and the six counties of what were to be Northern Ireland remained as part of the United Kingdom.

Are the four saints of England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales conveying a political message? Looking at this window today it is not difficult to spot this subtext in the window. If indeed the young men of Belfast died in the trenches to keep Northern Ireland in the United Kingdom and the young men of Andernach died to keep the Rhine German, then we may come to see the First World War has having been fought on the basis of a terrible misunderstanding. Because it seems unlikely that the men of Andernach had any strong views one way or the other about the Union. And we may doubt that the men of Belfast had any particular designs on the banks of the Rhine.

But, unlike the Andernach memorial, the window in St. Mark, Dundela, has words of Scripture as well as political messaging. These words of Scripture direct us back to main emotion felt by those who commissioned and made the window and the many more who have looked at it. Because most people must surely have looked at this window and simply resolved never to forget those who had died. And the verse from scripture guides our thoughts very much in this direction.

Two more windows on the south side of the church were installed at around the same time. These are more complex in their messaging. One is dedicated to a woman who died in 1917 and it depicts faith, peace and love with peace in the middle. Peace is a woman. And she is trampling on a sword. The image seems unambiguous in its intent. The yearning for peace, which by 1917 was so strong right across Europe, is preserved for future generations to reflect on in this window,

The other window is dedicated to the memory of just one soldier whose name is Major Lloyd Thompson. Paying for an entire window would have been beyond the means of all but the wealthiest members of the congregation, so when we look at this window we have to remind ourselves of all the other soldiers who died whose names only appeared on lists. But that said, it is a most extraordinary window.

On the left and on the right we have two Old Testament warriors, David again and Jonathan, this time facing him. Both of them look extraordinarily youthful; their boyish good looks are really striking which reminds us of the initimate friendship between the two of them which at one point crossed a divide because they were essentially fighting on different sides of a battle between David and Saul.

One wonders, looking at the window today, whether these images are a reference to a significant other in the life of Major Lloyd Thompson which his parents wanted to allude to. Maybe a significant other who had also died in war. Or whether this was also a reference to the young warriors who fought and were killed on the other side whose young lives were also full of promise as the lives of the young men from our own community who were killed. We can’t possibly know this, the meaning of the images is ambiguous but also powerful as it opens our minds to reflect on an actual life brought to an abrupt and violent end. As it happens, the word ‘love’ is written underneath the picture of Jonathan. David on the other side of the window has ‘valour’ written under him. And the central window has the word ‘sacrifice’.

And it is this central picture which is the most thought provoking. It depicts Abraham about to sacrifice Isaac. There, caught in the thicket, is the lamb which God has provided as the alternative sacrifice so that Isaac can be spared. But Abraham has not seen the lamb yet. His focus is on his son whom he is ready to sacrifice. It looks as if the son will not be spared just as Lloyd Thompson was also not spared. His life was taken at the battle of Cambrai as the words underneath the pictures describe.

In fact, the full text reads; ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Major Lloyd Thompson MC RFA who was killed in action at the Battle of Cambrai’. And then, underneath, ‘1st December 1917. This window was erected by his Father & Mother, Mr. & Mrs. James A Thompson of Penrhyn, Strandtown.’

Except, it’s slightly more complicated than that because the whole design stretches over three windows so that there are three panels which means that the middle section of the first sentence sits over the middle section of the second sentence in such a way that the casual reader may be forgiven for reading the sentence as ‘memory of Major Lloyd Thompson MC RFA who was killed by his Father & Mother, Mr & Mrs James A Thompson.’ Which one might assume to be an unfortunate error if it were not for the fact that the central image shows a father about to sacrifice his son.

We know about the guilt that the older generation felt about having sent their sons to die in the First World War. Rudyard Kipling began the war as an ardent supporter of the war effort and wrote propaganda for the British government. He even used his contacts to secure his only son a commission in the army after he had been rejected for having poor eyesight. His son, Jack, went missing presumed dead in 1915. Kipling senior wrote on his epitaph, ‘If any question why we died, tell them because our fathers lied.’ Did the parents of Lloyd Thompson have similar sentiments of guilt and were they trying to share them with their church in the design of the window for their son?

Looking at all these stained-glass windows, one may wonder where Jesus is. Because there are saints and angels and warriors and heroes from the Old Testament. But where is Jesus?

We could say that Jesus is in the window with Abraham with Isaac. He is the lamb of God whom God offers as a sacrifice so that Abraham and the other fathers do not have to sacrifice their sons. He died on the cross having refused to resist his oppressors and proclaimed a new kingdom based on love and forgiveness as he died. And we may wonder what that means for us today.

Of all the memorials under discussion here, I believe that the Thompson window is the one that does the most within a Christian faith tradition to say something about war and loss which will stand the test of time.

How does it do this? It remains faithful to Scripture, first of all, and it trusts in the power of Scriptural narrative. It invites us to relate the grief a mother and a father have for their son to the story of David and Jonathan and the story of Abraham and Isaac; stories that will have meant something to them and also mean something to us and to future generations allowing for new depths of meaning to be revealed over time.

And Jesus is also in the story in the shape of the lamb. We cannot entirely know what was going through the minds of Mr & Mrs Thompson when they commissioned a window for their fallen son. But by seeking to convey their emotions through stories in ways that are faithful to the original stories, they have ensured that their personal remembrance has a chance of timeless relevance.

Looking at the Thompson window, we are not looking at a political justification for a particular war. Rather, we are invited to enter into and share in the grief of a mother and a father for one fallen soldier and to do so in the presence of the grace of God who enters into our suffering.

The two memorials on the banks of the Rhine are not religious. They spell out to us how we should remember the dead in words of political opinion and sloganising. Gratitude for heroes. They died to keep the Rhine German. Messages set in stone that actually turn out not to stand the test of time. And some church memorials can find themselves in a similar place, especially if they take too many liberties with the Biblical text. They effectively become secular monuments gatecrashing a sacred space.

The human search for truth is unending and in the end it brings us to God. On Remembrance Sunday, it is the task of the preacher to help their congregation do the same. Not to be constrained by definitions and justifications for war which meant something once but do not speak to us now. But rather, to help us to adjust our understanding of the past in the light of the present using the eternal Word of God as our guide.

One final note about Andernach.

By 1970, the town of Andernach was no longer happy with memorial it had. But it didn’t take it down. It added to it. Just as in Zündorf , the names of those who had lost their lives in the Second World War were added to the victims of the First. And then a new plaque was erected which reads, ‘We remember in mourning all those who died in war and because of tyranny – the Town of Andernach.’ A bas relief was also added, not of a soldier wearing a helmet but of Picasso-style figures in imitation of his painting of the bombing of Guernica, depicting human suffering in war. And more recently a further plaque was added to explain the whole process and place it carefully into its historical context. It is a very effective updating and correction indicative of a community that is capable of adjusting its view of the past in the light of the present. The overall effect is to give an impression of a community journeying towards truth.

One wonders if something similar could not be done in Zündorf. Because time marches on. There may even come a time when we will have to get used to hearing thanks being given in public life in Germany for the so-called heroes who brought violence and death to Europe through tyranny and war. If the people of Zündorf look at the past differently now, maybe it’s time to reassess the memorial in the main square, and make a start on their search for truth.

Thank you for this insightful blog

Thank you, Robin, for this well-researched and well-presented essay.

The memorials described are telling us stories which need to be interpreted with an understanding of the context in which they were created. Thank you for helping see this in such an engaging and thought provoking way. Much for me to reflect on here!