This is an account of a visit to the Balkan History Museum located in the former Hidirlik fortress just outside Edirne in Turkey.

It is a reflection on the museum’s attempt to construct a historical narrative that is compatible with the ideology of the state and is both acceptable to and potentially transformational for the people who visit. Even museums with ‘History’ in their name tend to be more about remembrance than history because they inevitably have to make choices about what elements to include in the narrative and what elements to ignore. The choices they make determine the conclusions that the visitor is led towards.

So, in my visit to the Balkan History Museum I was interested to see which elements of the history of the Balkans were retained and which were discarded and whether there was a discernible message for the visitor to take away. And if there is a message, to what extent does this museum lead its visitors to making a commitment to peace with justice; ie. a peace which recognises our pain and also the pain of others, and does historical accuracy matter in this process?

And, of course, all the while, I was looking for parallels with British remembrance culture.

Edirne has a long history. It was founded by the Roman Emperor Hadrian (the one who built the wall) on a site that had already been settled for hundreds of years. For centuries, well into the Middle Ages, it was a Byzantine city but it also spent time under Bulgarian and ‘Crusader’ rule until it was captured by the Ottoman Turks in 1369.

After the Ottoman capture of Istanbul, Edirne became a sort of second city in the Ottoman Empire. In 1575, the magnificent Selimiye Mosque was built in Edirne. This is regarded as the finest work of the famous Ottoman architect, Sinan and it is truly impressive. Edirne became the base from which the Ottoman Sultans sent their armies to make further conquests in Europe (their armies reached the gates of Vienna twice in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries), settling new areas and bringing back booty and slaves. It became the tradition for the imam of the Selimiye Mosque to wear a sword when he led the faithful for Friday prayers in recognition of this crucial role the city played in the Ottoman Empire.

Edirne today is a city of 180,000 situated very close to Turkey’s border with both Bulgaria and Greece. Both the Selimiye mosque and the main shopping streets are undergoing repairs. There are many attractions to delight the visitor and many of the shops have signs in Bulgarian aimed at shoppers who have come over the border. Bulgarian shoppers and traders made up a significant number of the guests in the hotel we stayed in. Cultural tourists like us make up a smaller group but judging by the amount of construction that is taking place, the authorities have high hopes that more tourists will come.

There are several museums around the city including three separate sites that specifically focus on remembrance culture based on the period 1912 to 1923. During this period, Turkey participated in four separate wars; the first and second Balkan Wars, the First World War and the Turkish War of Independence, but, in many ways, as far as the Turkish people were concerned, they formed one long war which ended with the formation of the Turkish Republic.

The three museums are:

- The Balkan History Museum situated in the Hidirlik Fortress

- The Sukru Pasha Memorial (which celebrates the life of Sukru Pasha who led the defence of Edirne in 1912 – this memorial is temporarily closed and has been for some time)

- The Museum of the Treaty of Lausanne in Karaagac, just outside Edirne

We elected to visit the Balkan History Museum and took the number 3A minibus from town out to the suburb of Yildirim and followed signs to the museum. These signs actually brought us first to another memorial situated just outside Yildirim, which specifically commemorates the Liberation of Edirne in 1922. The memorial consists of an extremely large monolith bearing the words ‘one hundred years’. In front of this monolith is a statue of a woman, (possibly representing liberty or Edirne?) clothed in the European manner and alongside her there is a scuplture of Turkish soldiers made out of rusted iron.

Coming across this unexpected memorial led us to reflect on the significance of this date, 1922, for the modern inhabitants of Edirne. It was the date when Edirne was reoccupied by Turkish forces after the Greek occupation which had been agreed in the Treaty of Sevres in 1920. 1922 was the defining year when the city knew that it would, after all, be part of the Turkish Republic, so its centenary was worth celebrating, but why here, in the middle of a field on the edge of town? Why not close to the centre of the city?

This memorial was erected by the municipality of Edirne. The memorial’s position, round the corner from the main attraction – the national museum situated in the former fortress, made me wonder whether there was a competitive element to this remembrance. Was the municipality wanting to show it was not to be outdone by national government’s remembrance efforts? Earlier in the day, we had admired the outdoor exhibition of photographs of Ataturk’s 1930 visit to the city which was set up along the fence of the municipal building next to the Selimiye mosque. Are there competing narratives in Edirne?

Moving on to the Museum of Balkan History. This is a national museum located in a former fortress. After the Russian occupation of Edirne in 1829, a ring of fortresses was built and maintained around Edirne. In 1912, a joint Bulgarian and Serbian force besieged the city and its ring of fortresses. The Turkish garrison held out for a long time but in the end were forced by starvation and disease to surrender. The subsequent Bulgarian occupation of the city brought much suffering and humiliation. So the physical context of the museum is a story of heroism, defeat and suffering.

It is worth reflecting that there are very few equivalent experiences in modern England. One might draw a parallel with the Channel Islands, occupied by the German army 1940-45. Or Singapore, a British city in a way, which was also a colonial possession, occupied by the Japanese army 1942-45. Many large cities across Turkey experienced foreign occupation during the period 1912-22 and this is something that profoundly affects the intensity of Turkish remembrance culture.

So this is the emotive setting of a very large museum offering to present to its visitor a history of the Balkans. Unsurprisingly, the main focus of the museum is really the history of the relationship between Turkey and the Balkans and this story is essentially told in two parts.

The first part is a presentation of the years 1369 to 1912, the period of imperial expansion and administration when the Ottoman Empire ruled many parts of the Balkans up to the River Danube and beyond. Ottoman rule was presented as period of stability, peace, toleration of ethnic minorities and their religions and also great architecture.

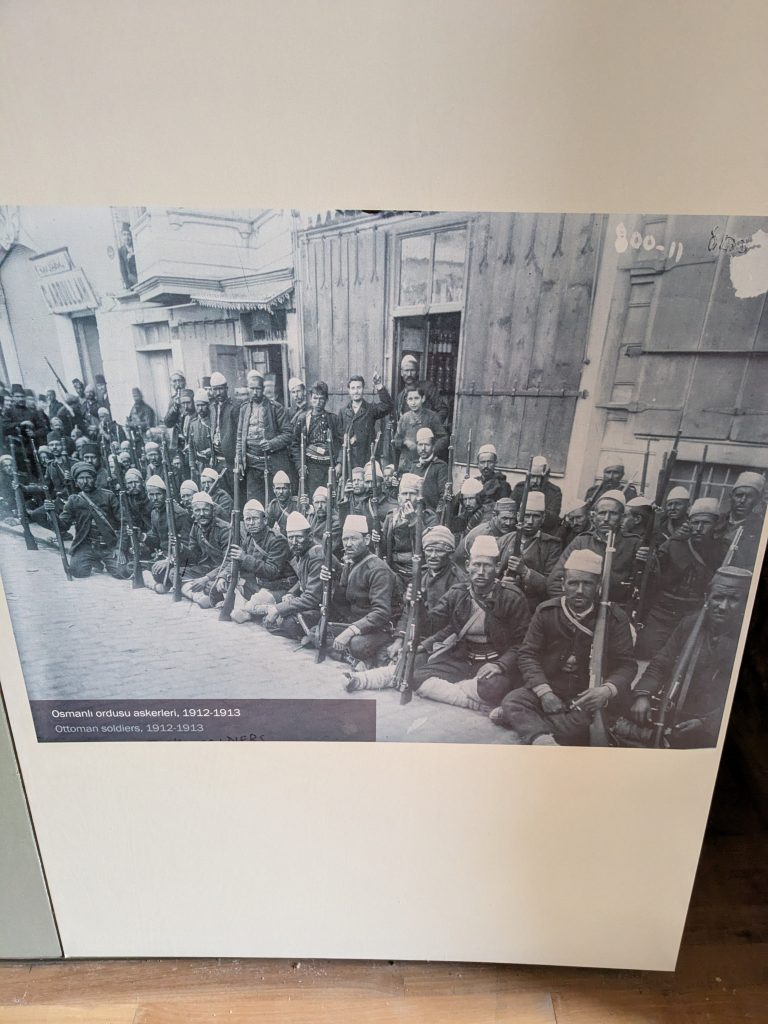

The second part of the museum deals with the Balkan Wars and their aftermath. Having presented Ottoman rule as a positive experience there is no basis in the narrative to explain why the governments of Greece, Montenegro, Serbia and Bulgaria should want to declare war on Turkey in 1912 other than to contrast the suffering that war brought with the peace and harmony that had apparently preceded it for hundreds of years.

This is therefore a story of violence and suffering that comes out of nowhere. Some of the atrocities are hinted at rather than spelled out in graphic detail, maybe out of respect for victims and their memory. The violence was suffered by the Turks, who heroically and entirely justifiably resisted it. The visitor is invited to feel gratitude towards those who gave their lives in the past. Without their sacrifice, things could have been worse and life in Edirne today would be very different.

Two historical omissions serve to tie the events depicted in the museum into a coherent national story about the formation of the Turkish Republic.

The first is that the museum includes a nineteenth French ethnographic map of the Balkans which clearly shows the presence of Turkish populations across the Balkans forming majorities in some parts of Macedonia and Bulgaria. What the map also shows is that rural population in Eastern Thrace, the area around Edirne, was majority Greek. This population was expelled from the area as a result of the Population Exchange of 1923. The map is the only reference to their part in the story which leaves the way clear, so to speak, to tell a story about heroic and justified Turkish resistance.

The second omission is a list of the martyrs who lost their lives in the defence of Edirne in 1912. The list includes their names and surnames and their place of birth. All the places of birth are within the modern boundaries of the Turkish Republic.

It is extremely unlikely that this list is a comprehensive list of all the soldiers who died on the Ottoman side. This is because the army that defended Edirne was an army which conscripted soldiers from across the Ottoman empire, from Arabic speaking lands and also from the Balkan territories like Macedonia which the army was fighting to defend. In short this was not a purely Turkish army in the sense of being made up of soldiers who spoke Turkish as their mother tongue or lived in what is now regarded as Turkey.

So what is this list there for? A clue comes from the fact that all the martyrs have surnames. In 1912 Turks did not use surnames; they were later introduced by Ataturk in the early years of the Turkish Republic; so these men did not have surnames when they died. But their families, living afterwards in the Turkish Republic would have had surnames and clearly mentioned them when the names of the martyrs were gathered years after the siege took place.

It is, of course, entirely appropriate to give an opportunity for people to remember the names of people who actually died in the battle for Edirne. But not all the names are being remembered here. And the ones that are being remembered are being remembered in a way that seeks to reinforce a narrative about the birth of the Turkish Republic and projects that narrative back into the story of the siege of Edirne.

A very powerful aspect of the museum is its treatment of refugees. There are several moving accounts of the suffering of refugees both from 1912 and from subsequent waves of refugees. Hundreds of thousands of refugees flooded into Turkey at this time and subsequently because of the persecution of the Turkish minorities in Bulgaria, Greece and Yugoslavia.

Particular attention is given to pictures of child refugees and this is expressly linked to the suffering of children in wars today, pointing out how extensive this suffering is. This section of the museum is equipped with seating for primary school age children and would appear to be specifically designed for use with this age group.

This focus on refugees is particularly relevant for the population of Edirne and Eastern Thrace. The fact that so much of the countryside was previously inhabited by Greeks who had to leave in 1923 meant that the area was then empty and extensively used to settle refugees and immigrants who were coming the other way so that today, Edirne and its environs is home to many people whose ancestors were refugees. And, today, refugees are once again passing through Eastern Thrace. We met some at the bus station.

The museum quotes Sevket Sureyya Aydemir, whose autobiography, called ‘A Man seeking Water’ includes this passage,

‘With new immigrants infiltrating across borders, the population of the neighbourhood increased day by day. After leaving their homeland back where they were born, those newcomers would take whatever they could, such as grains, utensils and blankets, and set off on heavy carts pulled by big cattle. Women and children sat on the load. Those miserable groups were the offspring, remains of the old conquerors of old invasion armies who settled and built villages, cities and castles in the Balkans, on the Danube and beyond.’

It is an intriguing quote from an intellectual on the centre-left of Turkish politics . What is he getting at here? Is he asking us to feel pity for a once proud people? Or is there a sense in which he is inviting us to consider that this is the fate of invaders: one day, maybe generations later, their descendants will be forced to leave their homes as refugees?

At the end of my visit, I was left feeling that it maybe called the Balkan History Museum but really it isn’t. It tells the story of the Balkans from a particular national perspective and in doing so it helps to construct a national identity. To do that it has to include some things and omit others.

Does this matter? After all, one of the concluding messages is about children suffering in war. Maybe it is enough if a museum working entirely within a particular national perspective can lead its visitors to a deeper understanding of the need for peace among the nations.

I think it does matter. I think a museum which sets out to talk about war and peace needs to confront visitors with the need to understand the pain of other people; people not like them. To duck this responsibility means that people leave the museum without any stimulation of their ability to listen to challenging narratives about the pain of others. And if we lack this ability, we are left insufficiently prepared for the challenges of the future.

Really a Balkan History Museum needs to be a joint venture. There is a need historians and curators from Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece and Turkey to come together and construct a museum where people can confront both their own pain and the pain of others.

Is this a utopian idea? Actually, in a way, it is an idea that museum itself advocates by including in its displays this quote from Ataturk, dated 26th August 1931.

‘Balkan nations have a shared history of centuries. If such history has sad memories, all of its nations are together to embrace them. The share of Turks is not less painful. Now you, respected representatives of Balkan nations, will overcome complicated emotions and accounts of the past and lay foundation of deep fraternity and open broad horizons of unity. You will reveal neglected and forgotten big truths.’

Ataturk carries a lot of weight in Turkey. Maybe a joint Balkan history museum that reveals neglected and forgotten truths and builds foundations of deep fraternity is possible. And maybe, this could be an example for the whole world. Maybe we could learn from this in Britain also.

I suggest that your initial premise limits one’s appreciation of the nature of a museum. I suggest below, by considering my visits to the RAF Museum Midlands, that a museum can be as much experiential as cerebral. I conclude by asking “Who are museums primarily for?”

You begin this essay by stating: “Even museums with ‘History’ in their name tend to be more about remembrance than history because they inevitably have to make choices about what elements to include in the narrative and what elements to ignore”.

In my experience, a museum is a building or place which presents historical artefacts, so a museum does not need to have “history” in its name to be concerned with history. In my experience, there are many kinds of museum, all of which are concerned with history but many of which have nothing to do with ‘war’ or ‘remembrance’.

I suggest that ‘remembrance’ is the business of a particular kind of museum, and that ‘war’ is the business of another particular kind of museum, and that sometimes these two categories overlap, but I am not convinced that ‘remembrance’ is the business of all ‘war’ museums or that ‘war’ is the business of all ‘remembrance’ museums. I think this is getting into the realms of anthropology about which I know nothing.

When I visit the RAF Museum Midlands at RAF Cosford, ‘remembrance’ does not initially enter my consciousness because my primary interest is in the evolution of military aircraft design and my memories of aircraft that I saw as a boy. I have noticed that in the last twenty years there has been an increased number of ‘human interest’ displays in the museum, and it does feel as if the museum is now steering the visitor more towards considering the people who flew the aircraft and who were otherwise associated with them, and those who suffered the consequences of the RAF’s bombing of cities in wartime. But, because of the scale and nature of their physical presence within a building with a strong sense of place, the military aircraft are the star of the show. This is not cerebral: this is experiential, in the realm of archetypes and symbols and resistant to rational argument. Even so, I am now led by the increased number of ‘human interest’ displays in the museum to contemplate ‘remembrance’ to a greater degree than before, but ‘remembrance’ is not my main ‘take away’ as I leave the museum. My main ‘take away’ is a sense of reinforcement of my personal identity.

I don’t use audio guides in museums because I prefer to let my senses engage with what is before me, rather than being bound to a voice in my ear. I don’t think the RAF Museum at Cosford does set out to talk about war and peace, although I might feel differently if I used audio guides.

After a visit to Cosford, I am not contemplating the pain of others but I have a hunch about this museum and other aircraft museums that the mainstay volunteers of these places are ex-military people, and that the long term personal cost of military service might drive such people to seek healing in the warm embrace of a reassuring military museum which does not present difficult challenges.

So I conclude by suggesting that the question is: “Who are museums primarily for?”

Here’s my Blog (Cold War Kid 02), started recently, late in life, as I revert to the plastic aircraft kit building of my childhood. Along the way, it will be musings on the Cold War, 20th Century art and artists, and our Judeo Christian inheritance: https://ajb2f109c96a1c0-lrfay.blog/2025/10/22/bobs-mosquito/