When they came to the place that is called The Skull, they crucified Jesus there with the criminals, one on his right and one on his left. Then Jesus said, ‘Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.’

Luke 23: 33-34

What is the Christian view of war and peace?

The experience of the Second World War is very prominent in the remembrance culture of the Church of England. In this remembrance culture, we reflect on the wickedness of the Nazi regime, the disaster for all mankind that a German victory in World War Two would have brought and so we are thankful that the victory went to the other side, the side that our country was on.

Even though I have a German mother and, through her, I have a window into a different remembrance culture, I have always carried within me the basic assumption that armed resistance to Hitler was necessary and, indeed, vital. So, based on this experience alone, I know that I have already conceded that war can sometimes be justified.

And this is a challenge for me as a Christian because I have also absorbed through the Gospel narratives, the idea that Jesus, in his life and death, rejected violence and called on his followers to pick up their cross and follow him, even unto death, proclaiming his kingdom of love and forgiveness.

This leaves me with a feeling that, if I am being honest with myself, I accept that sometimes it is necessary to wage war, while I also have a feeling that if I want to follow Jesus, this is wrong.

The idea that it might be justified sometimes to wage war is an idea that finds expression in just war theology. A modern exponent of just war theology is Nigel Biggar who wrote a book published in 2013 called ‘In Defence of War’. Nigel Biggar is an Anglican priest, a former professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology at the University of Oxford and a member of the House of Lords. So, he speaks with authority. I thought if I read his book I might find out why I am, deep down in my heart, a supporter of just war theology.

Biggar’s book absolutely recognises war to be an evil. It by no means glorifies war. His argument is that war must sometimes be waged to prevent an even greater evil.

For this argument to hold, Biggar explains that war can only be waged by those who have authority to do so, by those authorities who have a realistic prospect of achieving a victory that would, indeed, prevent a greater evil and has to be waged in a manner to minimise deaths of innocents and that does not glorify in the deaths of enemies.

In discussing actual instances of times when a decision was made to wage war, Biggar argues that these decisions can only be examined retrospectively on the basis of the information that was available to the decision makers at the time. He also argues that pursuing a national interest by waging war does not necessarily make that decision immoral because a decision to go to war may be both morally justified and in the national interest of a particular leadership group.

In searching for books that gave the opposite theological view, I focussed on two; The Politics of Jesus by John H Yoder, which Biggar himself references, and the more modern and accessible A Farewell to Mars by Brian Zahnd. The arguments of the two books are very similar. They both present a Gospel-based account of the ministry, life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ which calls the church to a path of peace.

Zahnd uses the story of Cain and Abel to paint a picture of a world based on violence. Jesus came into this world, he says, and revealed the existence of a different kingdom, a new kingdom that rejected violence. As he struggles to get his disciples to understand this, Jesus says, “The world cannot hate you, but it hates me because I testify against it that its works are evil.” (John 7:7) Jesus has come to testify to the truth and against a world that is evil; a world where violence rules.

The cross is central to the demonstration of this path of non-violence. Jesus could have overcome his enemies, but he chose instead the way of the cross which becomes a form of “shock therapy for a world addicted to solving its problems through violence.” (Zahnd)

Zahnd explains that he finds following Jesus in the way of cross hard, but he is sustained by the vision of the risen Jesus who proclaimed a Kingdom of Peace that he has already called into being. He cites the first words spoken in this new Kingdom as “Peace be with you”, the words the risen Christ spoke to the frightened disciples in the locked room. (John 20:19).

This is the Kingdom of Peace the church is called to proclaim to the world today. In other words, the church is called to reject violence in the name of the Kingdom of Love and Forgiveness that Jesus proclaimed. And this is hard. Constructing a Messiah who allows us to wage war and reveals a God who seeks to save the world through our violence, that’s a lot easier.

Yoder takes as his starting point the account of the temptation of Christ in Luke’s Gospel.

Then the devil led him up and showed him in an instant all the kingdoms of the world. And the devil said to him, ‘To you I will give their glory and all this authority; for it has been given over to me, and I give it to anyone I please. If you, then, will worship me, it will all be yours.’ Jesus answered him, ‘It is written, “Worship the Lord your God, and serve only him.” ’ (Luke 4: 5-8).

Yoder takes this to be a decisive rejection of the devil’s temptation that Jesus use God-given power to seize earthly power and rule through violence as an earthly ruler would do. He then charts this message of rejecting violence, including violence as a means for achieving social justice, as a central theme of Jesus’ ministry through to the Garden of Gethsemane. In the Garden Jesus pledges obedience to God even to death and specifically rejects violence again at the moment of his arrest.

‘When those who were around him saw what was coming, they asked, ‘Lord, should we strike with the sword?’ Then one of them struck the slave of the high priest and cut off his right ear. But Jesus said, ‘No more of this!’ And he touched his ear and healed him’. (Luke 22: 49-51)

Yoder explicitly links Jesus’ rejection of violence to his obedience to God’s will and describes human violence as a rejection of God’s power to save the world.

In order to sustain his arguments in favour of a just war from a Christian perspective, Biggar needs to address the arguments that Yoder and Zahnd advance. The arguments that Yoder and Zahnd present share the same strength: they are based on a coherent narrative of the ministry, life and death of Jesus. In contrast, Biggar is rather nibbling round the edges of their arguments with his three main objections.

The three chief objections Biggar makes to the idea of a Gospel of non-violence are:

- A reading of Romans 13

- New Testament stories about soldiers

- A reframing of Jesus’ apparent commitment to peace as an opposition to nationalist rebellion

Chapter 13 of Paul’s letter to the Romans opens like this:

‘Let every person be subject to the governing authorities; for there is no authority except from God, and those authorities that exist have been instituted by God. Therefore, whoever resists authority resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgement’. (Romans 13: 1-2)

Biggar argues that because the power of all governing authorities rests ultimately on their power to enforce the law through violence, Paul is accepting that their violence is sanctioned by God.

I find this argument rather unconvincing. One could just as well say that, by telling Christians not to resist the authorities who apply their law with violence, Paul is telling Christians to follow the path of non-violence. Which would make this a text which rejects violence.

Indeed, the end of Chapter 12 of Romans, which, of course, immediately precedes the words on which Biggar rests his argument, reads as follows:

‘Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave room for the wrath of God; for it is written, ‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.’ No, ‘if your enemies are hungry, feed them; if they are thirsty, give them something to drink; for by doing this you will heap burning coals on their heads.’ Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.’ (Romans 12: 19-21)

This seems to be a description of the hard path of peace that Zahnd describes, a path that rejects violence and actively loves enemies.

Turning to the stories involving interactions with soldiers in the New Testament, Biggar lists four of them:

- The soldiers who question John the Baptist. (Luke 3: 14)

- The centurion who appeals to Jesus on behalf of his servant. (Matthew 8: 5-13)

- The centurion who declares Jesus to be the Son of God at the moment of his death. (Mark 15: 39)

- Cornelius the centurion who converts to Christianity in Acts. (Acts 10)

All these texts are very rich in meaning and are, incidentally, wonderful for exploration on Remembrance Sunday. However, the only point that Biggar wants to make about them is that none of them mention the soldiers giving up their soldiering because they have had a decisive interaction with the word of God or become Christians. Surely, Biggar argues, if rejecting violence was key to the Christian faith they would have to leave the Roman army.

It’s an interesting point to think about and it helps us to understand what these stories are about.

These accounts are not merely about soldiers; they are specifically about enemy soldiers. If you are blessed to be a peacemaker, a child of God, you still need to know how to interact with enemy soldiers who bear arms against you. As peacemakers, here are the things we must remember about enemy soldiers:

- They are capable of responding to the call to repentance as the soldiers who spoke to John the Baptist did

- they feel love each other and act upon this love as did the centurion who came asking for his servant to be healed.

- they can respond to the crucifixion like the centurion who commanded the actual execution party that crucified Christ

- they can be filled with the Holy Spirit as Cornelius was.

For me, all these accounts support the arguments of Zahnd and Yoder not Biggar’s.

Biggar’s third argument is that when Jesus does talk about peace, he specifically commands this as an alternative to nationalist rebellion and this is the only context in which Jesus’ message of nonviolence is to be understood.

Taking this to its logical conclusion and, in conjunction with his argument based on Romans 13, we may say that Biggar believes that Christianity tells oppressed people not to fight for their liberation but does allow for powerful authorities to use violence to maintain their power.

In his ministry, Jesus mainly preached his Gospel of peace to members of an oppressed nation. For millions of us around the world today, this is something that is very easy to relate to because we also experience oppression because of our identity, status and relationship to the economic means of production. We feel powerless in the face of injustice. Violence may be a temptation to us but, in most contexts, violence does not offer us an easy route to a better world either. To us, Jesus proclaims a new kingdom based on love and forgiveness and tells us that the way to this kingdom is through nonviolence.

For a very small minority of people, it appears that they may have the power to determine the course of history through violence, To them the world looks very different than it does to the rest of us. What is the message of Jesus, the Prince of Peace, to this small minority?

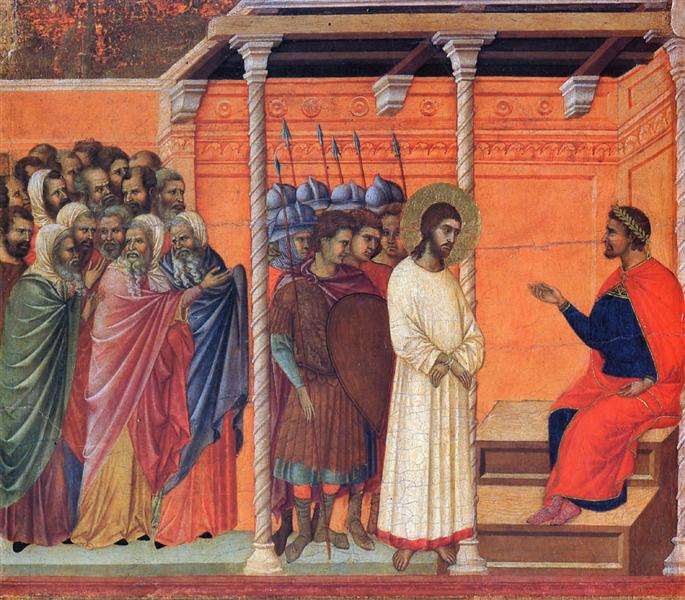

We know what the message to these people is because they are represented in the Gospel by Pilate. Here is the account of the encounter between Pilate and Jesus from John’s Gospel.

When Pilate asks Jesus if it is true that he is the King of the Jews, Jesus answered,

‘My kingdom is not from this world. If my kingdom were from this world, my followers would be fighting to keep me from being handed over to the Jews. But as it is, my kingdom is not from here.’ … (John 18: 36)

To demonstrate his power, Pilate had Jesus flogged and his soldiers invented their own methods of torturing him. Then he had Jesus brought back for another interrogation, but Jesus, initially refused to answer him. The Gospel account continues thus:

Pilate therefore said to him, ‘Do you refuse to speak to me? Do you not know that I have power to release you, and power to crucify you?’ Jesus answered him, ‘You would have no power over me unless it had been given you from above; therefore the one who handed me over to you is guilty of a greater sin.’ From then on Pilate tried to release him, but the Jews cried out, ‘If you release this man, you are no friend of the emperor. Everyone who claims to be a king sets himself against the emperor.’ (John 19: 10-12)

Pilate had the power of life and death over Jesus. He ordered his soldiers to flog Jesus. And yet none of this seems to have any effect on Jesus. Jesus testifies to a truth that Pilate cannot grasp, that ultimately there is no power through violence. Power rests in a different place. You cannot read this encounter between Jesus and Pilate and draw the conclusion that God endorses the violence upon which Pilate’s power rests. Rather, as we read this, we are asked to believe that real power does not rest with the Pilates of this world. It resides elsewhere. Pilate thinks he is powerful because he has the power to be violent. Jesus tells him that isn’t really what power is.

Reading Biggar’s book, I was profoundly disappointed with his attempt to argue from New Testament texts against the violence-rejectionist arguments of Zahnd and Yoder. Disappointed, especially, because I was hoping to find scriptural justification for my own position, that sometimes war is justified.

Biggar does discuss his ideas in the context of specific wars. He finds that Britain was justified in fighting the First World War. He finds that Britain was justified in fighting the Iraq War. In fact, there is very little mention in his book of wars that he doesn’t think are justified. He lists three: the crusades, the Spanish conquest of South and Central America and the Italian invasion of Abyssinia (now called Ethiopia). He doesn’t explain why he thinks these wars don’t count as just wars. And no war ever waged by the modern British state is mentioned as an example of a war that does not qualify as a just war.

Which leads me to the suspicion that, actually, when Biggar says that war may be justified if at the time the authorities think that waging war might be a lesser evil than the evil that would happen if war was not waged, that means in effect that any war the modern British state wages is justified. This leaves no basis for saying that a war is not justified. And this version of the doctrine of just war could just as well be used by the enemies of the British state. So, we are left with a philosophy that all sides can use to justify war. A position which condemns us to continuous war.

How does Biggar end up in this extraordinary position?

Primarily, by ignoring the overwhelming weight of New Testament Scripture.

But there are also three other deficits that I would have expected to see in defence of just war theory.

- All his analysis is done from the perspective of the powers that be – an analysis of the decision-making processes of the British state. There is very little attempt to look at things from the perspective of others – to understand the pain of others as Charlotte Wiedemann (in her book Den Schmerz der Anderen Begreifen published in 2022) so persuasively argues, is essential to good remembrance. Understanding what war is like for people who live in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Gaza, Ukraine etc etc seems to me to be essential for good decisions to be made.

- Every decision is analysed from the perspective of the information available to the decision makers at the time (except in some instances where hindsight might strengthen the case for war). There is no place for remembrance, for remembering what happened last time we had a war and how this might inform our decisions in the future. No allowance is made for learning to take place.

- While Biggar accepts that ‘once the dogs of war have been unleashed’ terrible things happen that those who made the decision to go to war may not have intended or foreseen, there is no account taken of the wider effects of war, by which I mean the trauma and brutalisation and the wider acceptance of the logic of violence; that if you have experienced defeat, the thing to do is to make yourself more powerful so that you are victorious in the next war.

So, my search for a theology of just war that I can live with remains ongoing. Far from finding an easy answer that suits my needs, I have found myself confronted by a Gospel that offers me only the way of the cross; the hard road that rejects violence. I find myself wanting to set out on that road, while also fearful of where that may lead me.

Biggar, whose arguments have been such a disappointment to me, does offer me a small window of hope. In arguing against Yoder’s call that the faithful trust in God alone to save the world, he writes this,

‘Faith does not require the abandonment of human responsibility, initiative and effort. Those who love God are bound to love the world he loves and those who love the world are bound to do whatever they can and may to see it prosper.’

I’m surprised he doesn’t explore this further. It’s the idea of humanity being invited by God to be co-creators of his kingdom. In Matthew’s Gospel, talking to Peter, Jesus says to the church, ‘I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.’ (Matthew 16:19)

It is an astonishing authority that God entrusts us with through his Son Jesus Christ. Having been given this authority, we need to make sure we know how we should exercise it.

Those who are responsible for the governance of a nation state must act on the information that is available to them at a given time. They will also take account of previous experience, expecting that, often, the past is a good guide to what the future holds. A government will always have its critics, but a government must make the difficult decisions. The principles of a Just War are the best rule of thumb that we have. One’s personal code of ethics may tend towards pacifism but the responsibilities of an individual are different from the responsibilities of the government. The church has a duty to uphold the morality that we inherit from Jesus Christ but many inhabitants of a nation state believe in no god: their moral values might align with Jesus Christ or they might not. A government will not necessarily look to the New Testament when deciding whether the nation should go to war.

Learning from the past may be seen by some to be a function of Remembrance Sunday but I have never seen it that way. As a serving Church of England parish clergyman over thirty-four years, standing among ex-service men and women, currently serving service people, those who have been bereaved by war and the increasing number of people that I saw attending Remembrance Sunday services, I saw Remembrance as primarily a matter of duty of respect towards those who lost their lives while serving with the British Armed Forces. There is an element of re-commitment to Christ in the Royal British Legion Remembrance Sunday service material, but I don’t see that we are there at the War Memorial on Armistice Day or Remembrance Sunday to learn from past wars.

Surely one of the most important important aspects of Remembrance is learning from past wars?

I am neither a Christian nor a pacifist but I cannot accept that duty to the nation state we find ourselves inhabiting is a valid basis for our attitude to war. As sentient individuals we have capacity and responsibility to make moral decisions based on historical experience and so Remembrance plays a role in this.

This does not detract from reflecting and empathising with those who have suffered in these conflicts. But considering the morality of past conflict must inform the decisions we make about wars in our own time. How I feel about WW2 in Europe fought in Europe to liberate the victims of Nazism is very different to how I feel about WW2 in Burma fought to defend imperial interests. And I had family members who participated, and suffered in both conflicts. I have a very strong sense that their sacrifice in the former was justified and should be emulated, whilst the sacrifices in the latter were tragic and should be avoided in the future.

Thank you Chris. Learning from past wars is I think essential if you want to persevere with a pursuit of just war theory. Just war theory without a ‘feedback loop’ seems to me to be very dangerous. And it is not what we actually do anyway. What happened in Iraq in the forst decade of this century obviously had an impact on decisions made in Syria in the second decade.

Powerful piece Robin and very sobering. Thank you. I’m quite enjoying reading your blog

The saying “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”George Santayana

Those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it … Winston Churchill

However I think Niccolo Machiavelli idea suggesting that human nature driven by the same desires and emotions leads to similar outcomes across different historical periods, sadly is true.

Wasn’t it Edmund Burke said for evil to triumph, it is only necessary for good men to do nothing.

The Bible says Micah 6:8 “He has told you o mortals ,and what does the Lord require of you , to do justice and to love kindness and to walk humbly with your God.”

How does one do this well without the need to stand up for oppression or injustice ? Do we need to go to war occasionally to do that?

Most wars I see have stemmed from a desire for power and wealth. I’m not sure that will change unless God changes our hearts as it is part of our fallen nature

Thank you Gina. It’s a dilemma isn’t it? We want to reserve the right to wage power to oppose oppression and injustice. But we want some basis to reject wars that are fought for power and wealth. Even the Second World War which we may think about as the war to oppose fascism ended with the British army re-establishing imperialism in South East Asia, even re-arming Japanese POW’s to fight against Vietnamese and Indonesian patriots, for example. So a war can be both about fighting injustice and also about grabbing wealth and power…

Great essay. What was your eventual conclusion? Do you still think the war against that Nazis was just? Or even that it was just from a christian perspective?

Biggar’s suggestion that war can be just but this can only be examined retrospectively doesn’t seem to offer any practical value for Christians faced with decisions about whether to pursue war. Presumably the suggestion is that the role of the church/the christian faith is an anti-war stance but that this is just one voice in the larger discussion on how to run a state?

It strikes me that a lot of the arguments made in the Bible against violence is that it isn’t necessary because the wrongdoers will be punished later anyway. That punishment is even described in quite violent terms e.g. ‘hot coals on their head.’ This seems to suggest that punishment is necessary, but that Christians don’t need to do it because God will. Is that correct?

If so, it seems like a compelling rationale for pacifism in the context of the early Church, when Christians were a small and persecuted minority. But is it still a workable ethic in a modern world where large and often aggressive Christian majority nations wield real power?

Looking forward to reading more of your blogposts!

Thank you Danny. I think one idea that I am drawn towards is that, despite the fact that some historical writing is aimed at finding ‘the main reason’ why something happened, actually, the world is more complicated than that. So, for example, it is important to remember that Britain did not fight world war two to defend universal human rights. Rather, the cause of war was the German invasion of Poland. Hitler was getting too powerful and the British state decided he should be stopped. And yet, even that decision was multi-faceted with, for example, the Labour Party being only too aware of the threat to the international Labour movement that Hitler represented. Also, as the war progressed, so the war aims changed, because of the need to keep a whole society motivated to support the war effort. And then there is the whole imperial dimension because, as well as fighting against Nazi imperialism in Europe, Britain was defending an empire across the world and even re-instated French and Dutch imperialism in SE Asia after the war.

The bit in the Bible you are thinking of is Paul’s letter to the Romans where he writes, ‘Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave room for the wrath of God; for it is written, ‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.’ No, ‘if your enemies are hungry, feed them; if they are thirsty, give them something to drink; for by doing this you will heap burning coals on their heads.’ Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good. (Romans 12: 19-21) I always feel this text is a bit like a friend stopping you from getting into a fight. (Leave it, he’s not worth it…) I don’t think it is necessarily that God will actually exact vengeance.

I haven’t read Biggar’s book so I can’t say if you have done his arguments justice. (Maybe you should read Aquinas instead!) But it seems too simple to me to look for *the* Christian response, as if there was only one. Clearly many sincere Christians share Yoder’s view — and many don’t. I think of my father and his brother, both thoughtful and devout Christians raised in the largely pacifist Brethren tradition. My uncle Peter was a conscientious objector in WW2, while my father felt it was right to serve in the Navy. They clearly had total respect for each other (and I never had the chance to discuss their decisions with them).

As for NT texts — I think there is a lot more to be said about Paul’s theology of ‘the powers that be’ in Romans 13 — which needs to be read against the very different theology of empire in the book of Revelation. Both have their roots in the experience of the Jewish people in living out their faith in a world controlled by hostile powers — but recognising that since it is still God’s world, the secular (and pagan) powers deserve a measure of respect inso far as any authority they have is derived from God. (It’s worth reflecting on the role of “the restrainer” in 2 Thessalonians ch.2 — a passage sadly omitted from last Sunday’s epistle.) I am reminded of the saying of Rabbi Akiva (who had experienced the full hostility of the Roman imperial state): “Pray for the peace of the government, for without it we would have eaten one another alive.” I think this is the context in which we have to read the NT injunctions to pray for those who exercise political power — and to reflect on the present (and ever-changing) relationship between church and state, which comes to the fore every year so strongly at Remembrance.

Another text which I find intriguing is Jesus’ injunction to love and pray for our enemies (Matthew 5.44ff). In 5.41, Jesus gives the example of what this might mean: “If someone compels you to go with him one mile, go with him two.” The word for ‘compel’ is the word used for compulsory requisitioning — a form of military service which the Roman army of occupation had the right to demand from every civilian. I think anyone in Jesus’ audience would get that he is talking about Roman soldiers here — and he seems to be saying, not just that we are supposed to love them (really?) but that we are supposed to comply cheerfully with the army’s demands. Typically of Jesus’ teaching, this raises more questions than it answers: are there any limits? What if the service they demand is unreasonable — or immoral? (The book of Daniel has some interesting stories about the limits of collaboration with the powers …). But I think (just as with the tribute to Caesar), Jesus often leaves us quite a lot of latitude in working out for ourselves what is right in any given situation.

Thank you Loveday. That’s a really helpful response. It still seems to me that all this teaching of the need to comply with the instructions from agents of a hostile occupying power might actually fit in more with a pacifist world view than one which regards force as sometimes justified. If you don’t fight the Nazi occupiers then you must, I suppose, be prepared to be conscripted as forced labour (as many were). Do you think this is what Jesus is teaching when he says when compelled to go one mile, you should go two miles?

Thank you for this excellent and thoughtful analysis Robin. Very well argued. In 1961 I attended a Christian peace conference in Prague, ecumenical and east-west. The group to which I was assigned was chaired by the patriarch of the Romanian church. We met under the shadow of the cold War between different socio-economic systems. In my group I managed to get into the

Protocol the statement that there is no such thing as a “just war”. I still stand by that. At the time everybody was getting ready for the next just war. Now they are doing it again. What rubbish. Hitler’s make Germany great again war should never have got started in the first place. People need to stop justifying wars and learn how to make peace instead. That is the lesson from remembrance.