When Jesus entered Capernaum, a centurion came to him, appealing to him and saying, ‘Lord, my servant is lying at home paralysed, in terrible distress.’ And he said to him, ‘I will come and cure him.’ The centurion answered, ‘Lord, I am not worthy to have you come under my roof; but only speak the word, and my servant will be healed. For I also am a man under authority, with soldiers under me; and I say to one, “Go”, and he goes, and to another, “Come”, and he comes, and to my slave, “Do this”, and the slave does it.’ When Jesus heard him, he was amazed and said to those who followed him, ‘Truly I tell you, in no one in Israel have I found such faith’.

Matthew 8: 5-10

Remembrance Sunday is a day when, all over Britain, members of the clergy look up and see strange people in church. Strange because they don’t normally come to church. But today they are here. And strange because we are aware that they have life experiences which we may not share and outlooks on life which we may not understand. Some are blazered up and wearing medals whose significance we cannot accurately understand. Others are not wearing any outward sign of being ex forces other than a certain ‘look’, a certain way of looking uncomfortable in church which we think might suggest ‘ex-forces’.

This may feel different to clergy who have worked as military chaplains. They may feel more confident about what their ministry to ex forces folk should be like. But I suspect that most clergy feel as I feel, that we are suddenly in a situation where a pastoral ministry might be needed or expected from us, but we are not really sure what form this ministry should take.

We should be very grateful, therefore for the passage from Matthew’s Gospel I have quoted above, because it describes his response to a pastoral situation involving an army officer. Jesus has just come down from the mountain where we has preached blessed are the peacemaker for they shall be called the children of God and other such beautiful sayings. The crowd are wondering how these statements are to be put into practice and, having come down from the mountain, Jesus immediately has two encounters with the brutal realities of the world as it actually is.

First, a leper issues this challenge to Jesus: ‘‘Lord, if you choose, you can make me clean’. And Jesus does make him clean. The crowd watch Jesus reversing the ordinary flow of holiness and grace. Because ordinarily if you touch a leper, it is the leper that makes you unclean. But this time, when Jesus touched the leper, it was he who made the leper clean. The world that was turned upside down in the sermon on the mount has also been turned upside before the eyes of the crowd on the plain.

And then an officer from an occupying army comes and asks Jesus to heal his servant. And the crowd see the flow of healing holiness and grace extend beyond their own nation and embrace their enemy; their oppressor. And on top of that the faith of this officer is commended and compared favourably with their own faith. His faith comes from his lived experience of military discipline. And Jesus commends it.

Does being a soldier really give you a basis for a life of faith?

Although I think of military life as a something of which I have no experience, actually I do have indirect experience of it. Like most people I have some preconceptions about military life shaped by the experience of my ancestors. It is always a good idea for a minister to examine his or her preconceptions. It may be necessary to consciously override them. And so now I shall examine mine.

The first person I met who was ex forces was my Onkel Emil. He was my great uncle having married my grandmother’s sister. His name was Emil Schmidt and for clarity’s sake, I will state that he was German. There was a bit of a tradition in my family of children being sent to stay with Onkel Emil and Tante Agathe for a couple of weeks over the summer and when I was about 10 years old, it was my turn to go. In all, I spent 3-4 summers at their house.

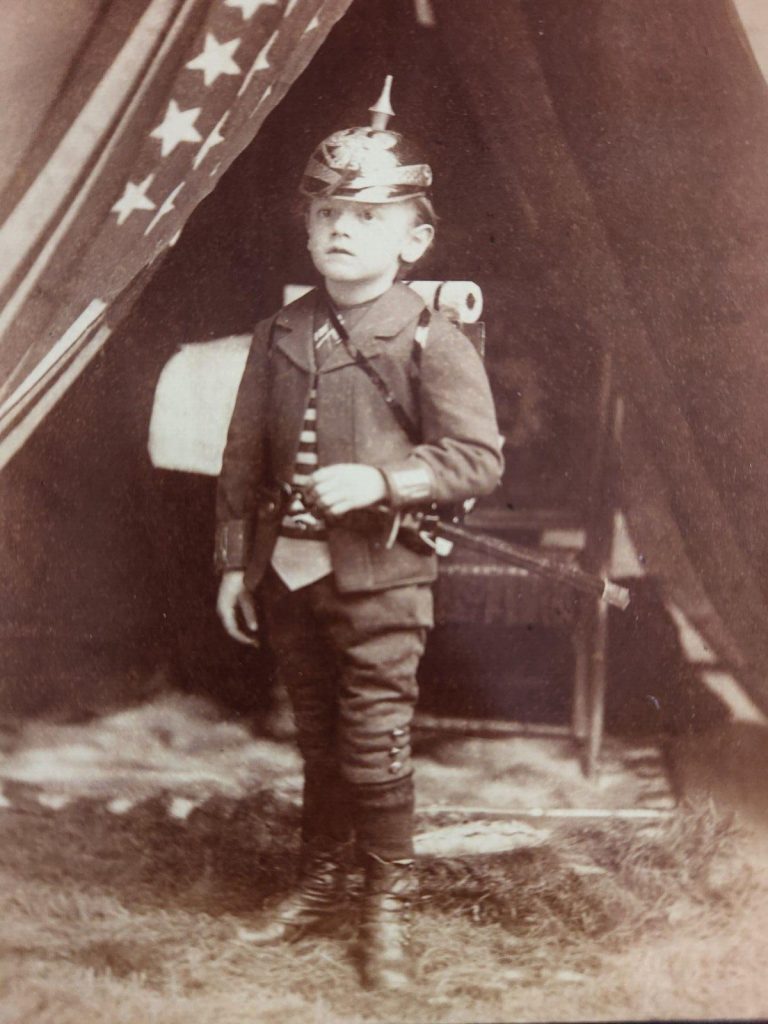

Onkel Emil was a blacksmith specializing in ornamental ironmongery. He had a workshop that had previously belonged to his father and he lived in a house over the workshop. His father had had an interest in collecting weapons and so Onkel Emil had inherited an impressive collection of weapons dating from the Thirty Years War. As well as that his father had also picked up a few items from the First World War, including some of the distinctive Pickelhaube helmets the from different regiments and a bugle. So, of course, I was very excited to try on a Pickelhaube and march around with seventeenth century halberds. This was a house where a boy could play at soldiering.

And while Onkel Emil never spoke to me about his war experiences, he would routinely refer to the fact that he had been a soldier. Life at his house was very structured and had what I assumed was a military flavour. It felt like your towels and toiletries were issued to you and your bedroom had to be kept in a certain way and had to pass inspection. I remember one time Onkel Emil saw that I had a hole in my sock. ‘A soldier has to know how to darn his own socks,’ he said and so Tante Agathe showed me how to darn socks.

The other thing about life with Onkel Emil was that he was a joker. He had a good sense of humour but it could be rough. It could be upsetting. It was sometimes bullying. And the effect it had on me was, as a boy away from home, I wanted to be in on the joke. I didn’t want to be the butt of the joke. Onkel Emil was very much in charge and you wanted to stay in his good books. And all the while, I had a sense that this world that Onkel Emil had built was a soldier’s world.

Things suddenly changed the day I brought my English girlfriend (now my wife) to visit Onkel Emil and Tante Agathe. Out of nowhere, presumably because he was suddenly faced by a real English person, Onkel Emil launched into a tirade against Churchill, about the bombing of German cities in the closing stages of the Second World War and his unwillingness to form a pact with Hitler to attack the Soviet Union.

And then, again, out of nowhere, and this was very much a one way conversation, Onkel Emil told a story from his own soldiering days. He said he and his comrades were in the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains. It was forty degrees Celsius in the shade. And he said to his comrades, ‘I hope we lose this war.’ And his comrades said, ‘Why do you say that Schmidt?’ And he replied, ‘because if we win, we’ll be spending the rest of our lives on guard duty in Outer Mongolia.’

I had always somehow assumed the Onkel Emil had been involved in a lot of the German invasions of the Second World War. But this was the first and only time, I ever heard him tell a story which placed his wartime military service in any specific context. Many years later, I bought a book about Onkel Emil and his father which was published by his the local municipality who had taken over the house and workshop after he died and turned it into a little museum. This book referred to Onkel Emil’s war experience, but claimed he has been a mechanic at a local air base. And, as so often happens with German memories of the Second World War, the younger generation is left wondering which version is right and whether they can somehow both be right.

A year after my first visit to Onkel Emil’s house, I was helping my German grandfather to split logs. As we worked together, I asked him what it had been like being a soldier in the war and to my surprise and joy, he talked and talked and talked, telling me story after story. That evening, after supper, he got an atlas out and turning to a page covering the western Soviet Union he traced his finger over the places he had been in the war. Thereafter, listening to Opa tell war stories became a regular event when we went to visit my grandparents.

There were two things that he always returned to when he told his stories. The first was that throughout the war he had a rifle strapped to his back and yet he managed to go the entire war without ever firing it. And the second was that the Russian people were a lovely people. Hospitable and clean and constantly referencing the common humanity they shared with my grandfather, they did not deserve to have their country invaded.

I loved listening to my grandfather tell these stories about a reluctant soldier who never did anybody any harm, whose survival at times bordered on the miraculous, who devoted so much of his energy to warning about the horror of war and the need to avoid future wars. Maybe it was because I loved listening to his stories that he finally wrote his memoirs.

Reading the war section of these memoirs, many of the stories were familiar to me. But three themes emerged in the written memoirs that I hadn’t really picked up on when I heard the stories in oral form.

The first was the impact of the initial training my grandfather had when he joined the army. Humiliation had been a key element in the process of turning my grandfather into a soldier. It was something that I recognised from Onkel Emil’s savage sense of humour.

The second was the close bond my grandfather felt with his comrades in his initial unit. His fellow soldiers were drawn from across Germany and from all walks of life. My grandfather reported that in the army he developed deep friendships with people he would never have got to know in civilian life, and this was something he had fond memories of, which he still remembered despite the subsequent traumas he experienced.

And the third came as a shock. When my grandfather was called up, his employer offered to go through the process to have my grandfather classified as exempt because his work was vital for the war effort. My grandfather was a graphic designer so this would have taken some effort on his employer’s part. It would have required his employer to pull a few strings but my grandfather thought this was not beyond what he could achieve. However, my grandfather disliked his employer (who was also a distant cousin) and hated the idea of being indebted to him and so, astonishingly, he preferred to be conscripted.

What had happened to the man of principle who was proud never to have used his rifle in the service of fascism? For my grandfather, serving in Hitler’s army felt like a better option in a life where he felt frustrated, undervalued, trapped and alienated. In this, I suspect he was like a lot of soldiers all over the world. Underestimating the horror of war before they have experienced it directly, military life seemed almost like a way out.

It was not what I had expected to read. I had assumed that my grandfather had no option, that the alternative to being a soldier was going to a concentration camp. I had thought that my grandfather would have refused to be a soldier if he hadn’t have lived in a totalitarian state. And I think this assumption was partly based on the other military story I had heard growing up which was my father’s story.

My father is English, just to avoid any confusion. He attended a single sex school which had a Combined Cadet Force (CCF). All the boys were part of the CCF. One day my father said he didn’t want to be in the CCF anymore. He was taken to see various teachers in the school. None of them could convince him to continue in the CCF. And so they made him learn classical Greek instead. Which, as it happens, he found quite interesting and useful. He had the freedom to choose. He had to be assertive in claiming that freedom. But he was assertive and he was given the freedom to choose and he chose not to be a soldier.

Why do I reflect on all this? Because on the one hand, I think of military life is a foreign country to me. I have never been part of the military and so I feel unsure of myself when I am suddenly expected to know what to say to members of the ex-forces community. But actually, it is not entirely a foreign country. Because stories of being a soldier abound in my family and were part of my childhood. My school had a CCF as well. By then CCf was very much a minority pursuit and in my year the CCF had real trouble recruiting new members. My form tutor urged me to join the CCF. I remember he told me he thought I was ‘officer material’. I was very flattered. And secretly I was rather attracted to some aspects of joining up. But, in the end, I didn’t. I didn’t because of my understanding of what the collective experiences of my father and grandfather had taught me. So actually, I do have assumptions about military life. And I need to be aware of my assumptions.

I have read two books recently in an attempt to get a deeper understanding about where the soldiers who come to my church on Remembrance Sunday might be coming from and I commend them both. The first is Call Sign Hades by Patrick Bury. Patrick Bury was an officer in the Royal Irish Regiment of the British army who served in Helmand province in Afghanistan. And the second is Veteranhood by Joe Glenton. Joe Glenton was a private rising to lance corporal in the Royal Signals Regiment of the British army who also served in Afghanistan. When he returned from Afghanistan he was diagnosed with PTSD, refused to redeploy to Afghanistan and went AWOL for almost two years before being court martialled and serving a short period of time in a military prison. Both books have subtitles after their main title. So, Patrick Bury’s book’s subtitle reads An Irish Platoon Commander in the most Dangerous Place on Earth, and Joe Glenton’s book’s subtitle is Rage and Hope in British Ex-Military Life.

It is probably apparent to you that these two books take very differing approaches to explaining modern military life, but coming to the subject from the outside, I was actually struck by many similarities.

First of all, the language of both books is not easy for a non-military person to decipher. The reader of both books is thrown into a world of acronyms and slang that requires a constant checking back to see what they mean. Both writers are conscious of this difficulty and try to overcome the barrier in communication in various ways, Glenton does this more effectively than Bury, but even so both writers take a reader like me anyway to a strange world where we just have to accept we don’t understand quite everything.

Glenton actually explains that this gulf is the result of a conscious objective of military training. He argues that military training is designed to take a soldier out of the society he once lived in, to cut him off from that society, make him suspicious and resentful of that society and to hold him in a state of preparedness to act with violence yet still under control. He quotes an ex-military social worker as saying that in any other context, military training would be regarded as abusive. He argues that the purpose of the abuse is to teach the soldier to rely on the approval of the unit and not of the society they have been drawn from. And the result of this military training makes the veteran’s return into civilian life problematic irrespective of their experience of combat.

Both writers describe the intensity of the relationship with comrades that I recognise from my grandfather’s memoirs. Bury shares a particularly emotional description of love between soldiers in the stress and trauma of battle. Glenton explains that loyalty to the unit is partly built through contempt for other branches of the same military and other ranks as well as contempt for foreign and domestic civilians. And this too I recognised from that feeling I had as a boy of wanting Onkel Emil to like me and hoping that he would exclude me from the contempt he clearly felt for the rest of the world.

I deliberately wanted to read books by soldiers who had been to Afghanistan. Glenton has a very helpful discussion of the different veteran cultures shaped by different wars that the British army has participated in. I think British remembrance culture as a whole is to a very great extent shaped by folk memories of a conscripted army of civilians who became soldiers to fight fascism and then returned to civilian life. But the younger veterans who come into our churches on Remembrance Sunday are making sense of of very different experiences and, in my experience, may even resent remembrance being discussed through a WW2 shaped lens. The newly established Afghanistan Veterans Community’s website might give you a flavour of this.

Glenton is, as you might expect, more critical of British participation in Afghanistan than Bury is. He worked in what was essentially a warehouse for munitions and so saw first hand the scale of destruction being visited upon that country in which roughly 250,000 people died during twenty years of fighting only for the Taliban to return to power. But in some ways, Bury’s book is even more critical of the way the war was prosecuted as it described the split second decisions he had to make as an officer, never sure if he was directing his men to fire on ‘insurgents’ or ‘civilians’.

In a way, the Afghanistan war represents a crisis in British remembrance culture. British remembrance culture is built around two world wars which ended in victory. Lives were lost but the victories won allows people to come to a conclusion that sacrifices, while painful were necessary and ultimately worthwhile. It is difficult to present the Afghanistan war as anything other than a defeat, especially in the light of the ignominious end to the war. And what of the war aims? Essentially, the British military was in Afghanistan because the US military was. And when the US left, the British left as well.

What happens when an army of traumatised soldiers returns from a war fought for war aims that our society does not entirely support and which ended in defeat? They have already been through training that sets them apart from the society of which they were once part. How do they reconnect? Where do they find understanding for what they have been through and the value systems they have created to make sense of it all?

Both Bury and Glenton describe the process by which they decided to become soldiers. Bury always wanted to be a soldier ever since he played at being a soldier as a boy. I remember that feeling of wearing a German Pickelhaube helmet and blowing on a bugle. It was a good feeling. I imagine that’s what Onkel Emil’s childhood was like all the time. Bury had a similar childhood and he took it all the way and went to Sandhurst. Glenton’s story is very different. After a somewhat chaotic childhood and without many qualifications he had few options. Suddenly the army seemed like a good idea. A bit like my granddad.

Glenton is very keen to make sure the reader understands the circumstances that lead most rank-and-file soldiers to join the military. It is a decision arrived at where there are few options. Writing with the authority of a man who went to prison rather than go back to war, he entirely rejects any attitude towards veterans which involves reproaching them for having gone to war. In Glenton’s view, such an approach serves no purpose. And in any case, the church is called to proclaim forgiveness and healing not dish out reproach and blame. Jesus didn’t upbraid the centurion for being a soldier. He healed his comrade.

So, what are the pastoral needs of veterans? And in what ways can ministers of religion meet these needs? Glenton is very dismissive of the efforts of military chaplains. He presents their ministry as essentially one of reassuring people that what they are doing is justified. I don’t have any experience of military chaplaincy and, in any case, my ministry is different because I don’t minister to serving military personnel. I want to work out what my ministry is towards veterans who choose to come to church, even if it is only once a year.

I go back to the idea that veterans have had their link to the society they live in broken. It is the idea that Glenton theorises about rather persuasively, but it also shines through in Bury’s writings. Veteranhood is a state of disconnection with society.

This state of disconnection may be exacerbated by the effect of trauma. Glenton describes his experience of PTSD. In particular, he describes resisting the diagnosis because he knew that other people had suffered worse things than he had suffered, until eventually a therapist pointed out how irrelevant this was. If you experience trauma that results in a stress disorder then you have to address that independently of any feelings you may have about what other people may have suffered and how it may have affected them.

Glenton’s observation struck a chord with me. At the age of 86, my mother, sent a message on a family WhatsApp. She said she thought that she had been traumatised by her war experiences. Her children know what she experienced in the war (she survived being bombed out, she hid under a train that was being strafed by fighter planes and watched soldiers shoot dead an unarmed civilian). So, for us she was stating the obvious. And then she wrote that she knew that other people had suffered much worse than she had. And that’s when we all understood why she had not allowed herself to admit before that she had been traumatised and it had affected who she was. It’s as if, in the emotional economy of war induced trauma, there is a quota of how many people can say they have been traumatised. Which is a nonsense if you think about it. The takeaway here is that people may not have given themselves permission to talk about the trauma their experiences have given them because they are only too aware that some people have suffered more than they have.

But even without traumatic experiences, if Glenton’s analysis is correct, the experience of being in the military is one that must by definition make people feel disconnected from society and it can so easily lead to a sense of alienation, of feeling misunderstood, of feeling angry, of craving a recognition which is being denied.

How can people who feel these things receive healing?

I think the encounter between Jesus and the centurion is so helpful in this regard and it makes an outstanding text for a Remembrance Sunday service. When Jesus commends the faith of the centurion, I think we tend to assume his only intended audience is the crowd of onlookers whose eyes are popping out at the thought that a Roman centurion may have a faith stronger than any in Israel. And this is certainly part of the message of this text.

But Jesus makes his words work hard and achieve more than one thing at once. So, we should also try and imagine the impact these words would have had on the centurion himself. He has heard this prophet of a conquered nation commend his faith before the crowd of people who will have harboured hostile thoughts towards him. His faith has been commended as something others might seek to emulate. How will he have heard these words?

The faith that Jesus is commending is partly the faith he has that Jesus has the power to heal his comrade. But it is not just that. It is also the faith he has in the relationships that hold a military unit together. It is a faith in the discipline that every soldier will carry out his role. And it is a faith that soldiers will always look out for each other, just as he has come to the foreign prophet seeking healing for his servant. This is a faith based on military comradeship which I recognise in the writing of Glenton the deserter, Bury the officer and my grandfather, the graphic designer who rashly became a soldier for a while. Jesus is commending the faith that rests on the love that soldiers have for each other.

And what is transformational about these words from the perspective of the centurion is that this love between comrades that he takes for granted but imagines is only relevant in a military context, in fact, has currency in the wider world. Indeed, it is a powerful force that can and will transform the world.

Jesus is saying, ‘This love you feel for each other, this way you assume that you will automatically serve each other, this is actually the way we all need to behave towards each other – this is how civilians should behave towards each other – this is how you can behave towards people who are not part of your unit; people who are not even in the same army as you; people who are not even in an army at all.’

I wonder how the church can find a way to say this to veterans, including and maybe especially to those veterans who went and fought and lost and came back defeated.

That comradeship that you experienced, is actually your way to reconnect with the rest of society. It is the way to overcome feelings of alienation and anger and of feeling unvalued and misunderstood. More than that even, it is your special gift to the world. You have learned the value of solidarity at a level human beings do not normally experience. Now you can share this level of solidarity with the world. You have learned how to serve your unit. Now you can serve the whole world in the same way.

My grandfather tells a very strange story in his memoirs. Right at the end of the war he was riding in a truck full of tinned meat which formed part of a convoy of food supplies. The convoy would make its way along bombed roads following orders to take the food to one destination only to be redirected before they arrived as the Americans continued their advance and the front line kept moving further East.

One of the soldiers attached to his unit was a Ukrainian. My grandfather describes his face as being a face full of love. It is not really clear from what my grandfather wrote what it was that this man actually did. All around them was destruction and chaos and inevitable defeat – a defeat which would offered this man nothing but uncertainty and danger and, probably death. But in the middle of this, this man went about his work, whatever that was, with love for all people.

As a boy, I heard this story several times, and at first I would always wait for the punchline. What happened to this man? How did this man’s love transform some situation? This is what a narrative arc demands. Some kind of denouement. But the story just ends with this: as the third Reich collapsed, a man from Ukraine went about his work with love for all people written all over his face.

After a while, I realised that my grandfather had a feeling that in this man’s face, he had seen the face of Christ. And my grandfather never forgot it. And I think it gave him the healing he needed.

Like you I have no real military experience – although I was a corporal in the cadets; I found field exercises and shooting rather thrilling as a teenager but now I am rather ashamed of it. Teenage boys find these things exciting; I was only a couple of years older than my great uncle who ran away from home to enlist underage in WW1 and who was killed in action shortly after his 18th birthday. Perhaps our motivations weren’t so very different.

Certainly for my generation Remembrance is inextricably linked to family history, and the traditions of Remembrance are grounded in the two world wars. I think this is key – the image of citizen soldiers or civilians in uniform lends itself to notions of sacrifice for a greater good.

But there will soon be no veterans of that era left, and for the professional soldiers of later generations Remembrance inevitably represents something different.

Going back to my own family history, my great grandfather and his own father were professional soldiers in Victoria’s armies. Before Kipling made the common soldier a sympathetic and heroic figure, British public opinion was not very pro-military. Drawn from the ranks of the poorest of the working class with a reputation largely as a brutalised hard-drinking and hard-fighting necessary evil, consistent with the Duke of Wellington’s description of the rank and file as ‘the scum of earth’. My ancestors undoubtedly took the queens schilling to avoid the slums of the nineteenth century East End. They served throughout Victoria’s empire in Ireland, India, the North West Frontier and South Africa. From a modern point of view the moral purpose of their service appears extremely questionable. I also doubt that they were motivated by any higher purpose I know that my great-uncle’s father (himself an ex-soldier) tried to prevent him from volunteering in WW1, necessitating my great uncle to run away to enlist in a town outside London.

I suspect that above all their motivation was loyalty to their mates and a strong sense of pride in doing a job which most people could not understand and would not be prepared to do if they did. In a sense it is just an extreme version of the experience of many working class jobs. I met many miners during the strike in the 80s and they had a similar mentality.

Physically dangerous heavy industry jobs are rare these days (but not extinct) however perhaps there is a parallel with those whose work is traumatic and not generally understood; NHS workers, emergency workers, social services, even teachers. Perhaps as the memory of the world wars slips from daily life and into history it is time to reinterpret Remembrance as a time to commemorate service in a broader sense.

Thank you for this fine writing Robin. As the boy who left the CCF (Robin’s father) I have one point to clarify. Starting off in the comradely group was ok, stomping about in polished boots and being shouted at. Abaaat turn! But then came the day when I first aimed a loaded rifle at a target, and realised as I hit it that it would be a person. So I laid the rifle down and walked off. Now if everybody did that, wars would cease. There would not be “a time to kill”. As Jesus said, in another place, ” Put up your sword”.This is not just escapism. The call goes out to work creatively for peace.

Thanks Dad! That is an important addition to the story.

Robin – I think this is very good.

What I remember Opa saying in his memoirs about the reason he didn’t accept his employer’s offer to get him excused from military service, is that others did not have this option. He felt he had no right to evade the fate that all those around him had to face. I agree it is the hardest part of Opa’s memoirs to understand since he was also very clear that he opposed Hitler and did not want to fight for him.

Thanks Jocelyn. I will look up what he actually wrote and get back to you!

This is all utterly fascinating to me especially as we share that family history – and I am grateful to be able to read about some details that I didn’t know. The two books you talk about so thoughtfully sound fascinating. I am however troubled by the passage from the bible. It seems to equate Christian faith with the forced obedience shown by soldiers and enslaved people to those who have power and authority over them. Jesus appears pleased that the centurion believes he can cure the centurion’s servant simply by ‘speaking the word’ ie. giving the command. It is portrayed as analogous to the authoritative pronouncement of a military commander and enslaver. You also mention he is the commander of an occupying force, an aggressor. And Jesus holds this up as a good model of faith. The validation of this structure of command and faith coupled with oppression and authoritarianism is what troubles me. Soldiers who fight on this model alone surely have no way of ensuring the justness of their fight.

Thank you Jocelyn. You make a very valid point. And some people in the church do seem to interpret this text as being one about blindly following orders. Which was a quality Hitler very much admired in his followers. I think there is much more to this text than that, not least because where it is placed in Matthew’s Gospel after the sermon on the mount and other sayings of Jesus, all of which are challenging us to be better people. So I think this encounter with the centurion is recorded and placed here to work as a transformational story for people who read it. For the presumably mainly Jewish onlookers, the transformational challenge is to accept that people not like them might have faith and might be good people. But it was only very recently that I even thought about how this encounter might have been a transformational challenge for the centurion himself and any of his soldiers who were also present. I think Jesus is inviting them to consider that the solidarity they have for each other is actually something they could extend to all people. In other words, instead of taking their moral weakness and admonishing them for it, he takes their greatest moral strength and essentially says, ‘do more of that.’

I like that idea, take your best thing and ‘do more of that’!

Fascinating thoughts giving me more to explore. Knowledge of the context of the gospels and scriptures from a Jewish perspective are not often shared. Thank you Robin