You shall not deprive a resident alien or an orphan of justice; you shall not take a widow’s garment in pledge. Remember that you were a slave in Egypt and the Lord your God redeemed you from there; therefore I command you to do this.

Deuteronomy 24: 17-18

In setting out its rules for how society should work, the Book of Deuteronomy records the word of God, repeatedly reminding his people of their previous powerlessness when they were slaves in Egypt. This remembrance of powerlessness is used to support a commandment that power should always be exercised in the community of believers with justice and with mercy.

One of the functions of remembrance is to help a community remain faithful to the values it has chosen to embrace. In order to do this remembrance has to be willing to adapt and change. It cannot remain static. It is a dynamic process. What we remember about the past affects the way we look at the world today. It is not always true to say that the past that shapes our values. Sometimes, it is the values we choose to embrace that shape our remembrance of the past.

***

In 1978, a five-part TV programme called ‘Holocaust’ was aired in the United States. It was a drama focusing on how the holocaust affected one German Jewish family. Soon afterwards, it was broadcast in the United Kingdom. I remember watching it with my mother. I would have been 16 years old. We had previously watched the ‘World at War’ documentary series produced by Jeremy Isaacs. These two TV programmes had a lasting effect on me and shaped my remembrance of the Second World War.

It was deeply significant to me that I watched them with my mother. She had lived through these times, having been born in Darmstadt in Germany in 1939. Obviously, I wanted to know what she remembered and how she reacted to what we were watching. I got the impression at the time that these TV programmes were joining a lot of dots for her. Her own personal memories were being connected to events on a wider plane.

In 1979, ‘Holocaust’ was also broadcast in West Germany. It had an enormous impact. It is estimated that half the adult population of West Germany watched it. After each episode was aired, a companion show was aired in which a panel of historians answered viewers’ questions by telephone. Thousands of shocked and outraged Germans called the panels. The German historian Alf Lüdtke wrote that the historians “could not cope” because thousands of angry viewers asked how such acts had happened. Despite the late broadcasting times almost half the audience of the miniseries watched the panels, and 30,000 callers overwhelmed stations’ telephone lines.

Today, it may seem strange to us that a TV dramatization of the Holocaust would have this kind of impact in Germany in 1979. Surely, people would have known about the Holocaust already? Did they not learn about it immediately after the war, if they had not been aware of it while it was actually happening? The answer is that they did know about it, but knowing about something and deciding whether or not it is significant are two different things. Remembrance isn’t just remembering. It is about agreeing as a community to attach significance to a memory.

Harald Jähner, in his book, ‘Aftermath – Life in the Fallout of the Third Reich’, devotes a chapter to how in public life immediately after the war, there was very little discussion about or reflection on the holocaust. The term itself was not used at the time.

He quotes Hannah Arendt, the German Jewish intellectual, who returned to Germany after the war from the United States and described what it was like when she told people in Germany that she was Jewish.

‘There generally followed a brief awkward pause; and after that came – not a personal question, such as, ‘where did you go after you left Germany?’; no sign of sympathy such as, ‘What happened to your family?’ – but a deluge of stories about how Germans have suffered.’

This rather fits with my mother’s memory of those times also. Her family were bombed out of their home in Darmstadt and eventually came to the small town of Mosbach where they eventually lived in a small flat vacated by her grandparents. Just a few minutes from where she lived was a ‘camp’ or ‘Lager’. After the war this was used to house people who had fled from territories in Eastern Europe that had formerly been part of Germany. Many such people were settled in Mosbach and neighbouring towns and villages. During the war, the camp had been used for forced labourers who had been put to work in a nearby armaments factory.

My mother told me that growing up in Mosbach, the talk in school and in the community was of the terrible suffering that German people had been through and the difficulties they were still struggling with. Her father, my grandfather, had survived the war and had come home, but around half the men in the extended family did not, and the pain and sorrow this caused was also a dominating theme. Acknowledgement of the suffering the Hitler regime had caused in the name of the German people was only rarely expressed, and when it was, it felt very much like you were expressing a minority perspective – you were not saying something significant – it was true but it wasn’t what we were attaching significance to.

The town of Mosbach is right next door to another small town – Neckarelz. There was a concentration camp in Neckarelz and now there is a KZ Gedenkstätte, which one might translate as ‘Concentration Camp Memorial Site.’ I mentioned this to my mother and she was surprised. Growing up just up the road, she had not heard of the existence of this concentration camp. I resolved to pay a visit to the Gedenkstätte.

Walking from the train station to the Gedenkstätte you have to go past the cemetery. At the entrance to the cemetery are two rather prominent war memorials. I resolved to go and take a quick look.

As one might expect, I was soon looking at a sobering list of names. The First World War memorial said, ‘In memory of those from this community who died and went missing in the war 1914-18.’ And underneath it said something I am going to struggle to translate, but is something like; ‘In honouring memory of the fallen, in grateful remembrance of the present and for future emulation.’

And then next to that is a much larger memorial to those who one might say did emulate the fallen of 1914-1918 because they died or went missing in 1939-1945. Again, a sobering list of names, but alongside that, just two words; ‘Peace’ and ‘Commemoration’. And a cross and two crowns of thorns. It was a more obviously Christian memorial than the one for the First World War. And one that was much less prescriptive of what anybody visiting was supposed to think about all these deaths.

What was really striking about the list of names, apart from its sheer length, was the fact that the names were divided into two groups; ‘Local’ and ‘Heimatvertriebene’ which is one of those assembled words in German that says so much in just one word. It means ‘those who were driven out of their homeland’ and it refers to the many German and German speaking refugees from Eastern Europe who were expelled from or driven out of their homes at the end of the Second World War who came to settle in Neckarelz. Among many other traumas, they brought with them their grief for loved ones who had died or who were never heard from again. Astonishingly as it may seem to us now, when the list of names for the memorial was compiled, it was decided to differentiate between locals and these newcomers.

But I needed to get onto the Gedenkstätte. I wondered if prisoners who had died in the concentration camp might also be commemorated in the cemetery, maybe even alongside the soldiers who had died, but I saw no sign of this.

The Gedenkstätte is open on Sunday afternoons and is run by volunteers. I knew this before I went and, somehow, this knowledge dampened my expectations of what I would find. In fact, when I got there, the Gedenkstätte was very impressive. Huge efforts had gone into collecting a wide range of artefacts and eyewitness accounts and they were displayed in a very powerful and imaginative way.

The Gedenkstätte was established in 1998 by a community organisation founded for that purpose. In the early days there was local opposition to the establishment of the Gedenkstätte and even some scepticism about whether there ever was a Concentration Camp In Neckarelz. A generation later, the situation is very different. The Gedenkstätte is now located in the playground of a school because the school building itself actually housed the concentration camp. Thus the children growing up in the community are growing up with this powerful remembrance as a normal part of their world.

What is so striking about visiting the Gedenkstätte is that you become aware of a community that has developed a new form of remembrance in living memory and has done so despite local opposition. The community organisation that has led this process has not been afraid to carry out painful work. It has been motivated by a search for the truth and, more than that, a search for what is significant for future generations to remember. The Gedenkstätte remains separated from the memorial to those who died as soldiers in war, but, it seemed to me, was likely to be playing a far more prominent role in the remembrance of children and young people in Neckarelz than the war memorials in the cemetery were.

While I was in the area, I thought I would squeeze in a visit to Mosbach itself, the town where my mother had lived. I paid a visit to the town museum and, in particular, to the section devoted to the Jewish population of the town. Mosbach is a small town and a very old town, a local centre of commerce and industry and also a market town for the surrounding villages. In the nineteenth century around 5% of its population was Jewish and it had its own synagogue and rabbi.

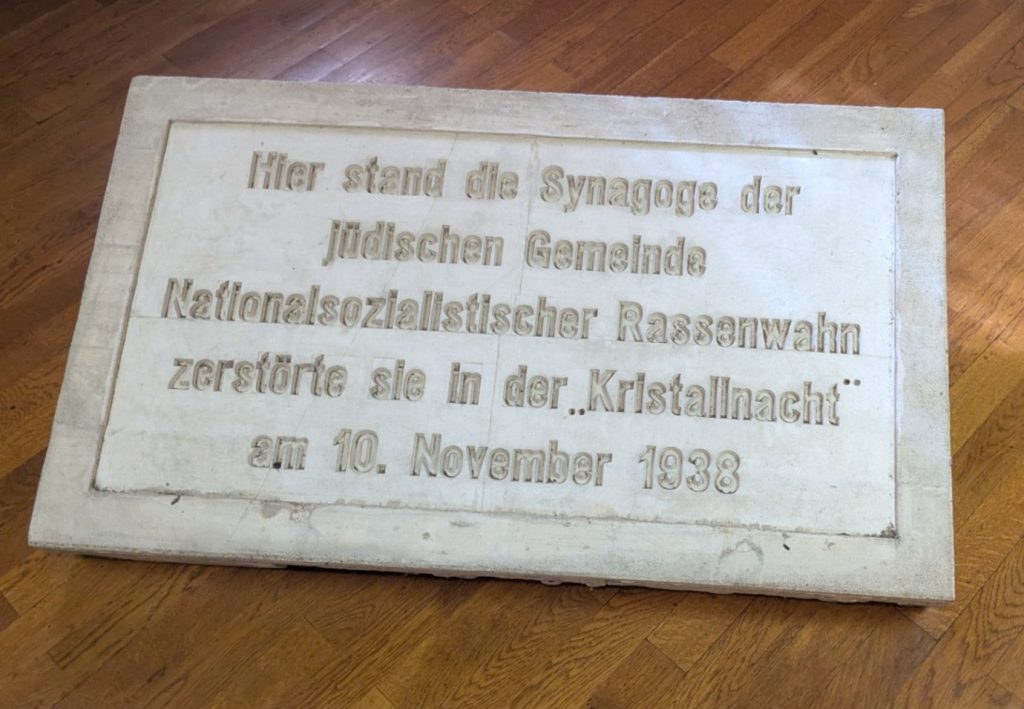

When it comes to honouring its Jewish history, the town museum faces the challenge of having very few surviving artifacts to tell this story. Three types of artefacts dominate this section of the museum. The first are advertisements from local newspapers from local Jewish businesses that locate the Jewish community firmly in the streets of the old town. The second are documents from the files of local government officials who carried out the measures the Nazi government implemented to restrict the lives of Jewish people in the 1930’s. And the third are photographs and accounts of Kristallnacht in Mosbach when the synagogue was burned down and its contents brought out into the main square to be burned. It seemed like the whole town turned out to watch.

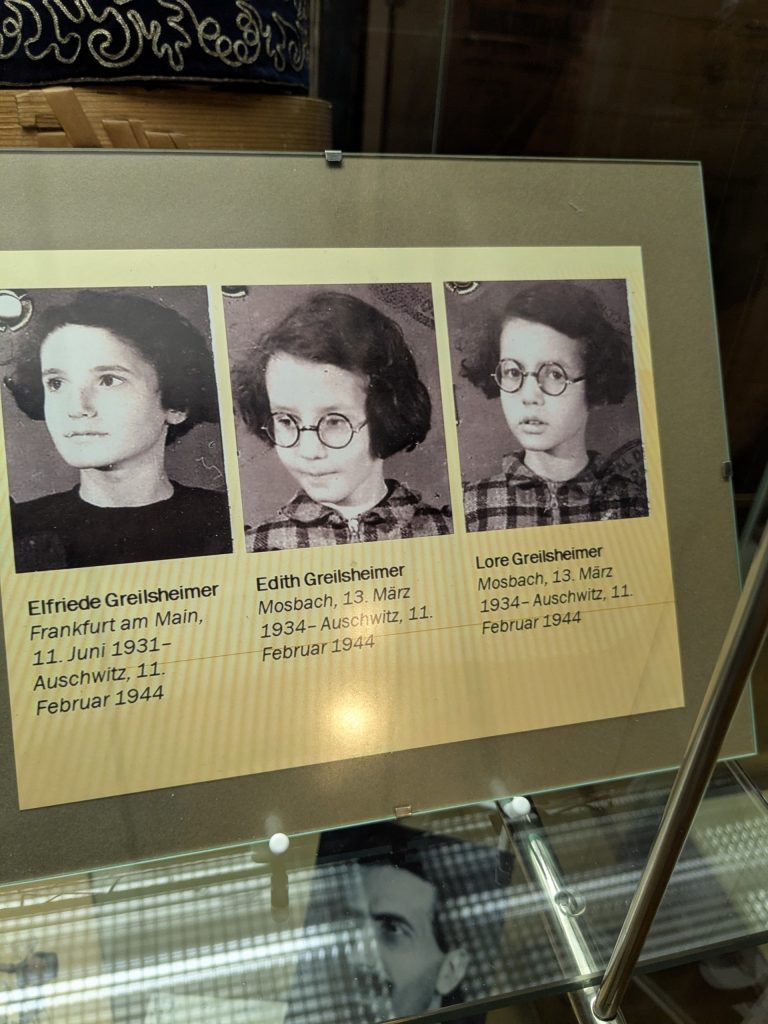

The museum has also managed to locate photographs of local Jewish people who were killed in the holocaust and is able to tell a small part of their story. This means that local people can look at photographs of children that were murdered in Auschwitz knowing that they once knew the same streets that are familiar to them today. Thus statistics become real people.

One of the things that the museum explains is that violence against Jewish people was nothing new. It mentions massacres in 1298 and 1349. It could also have mentioned anti-Jewish riots in 1848. The Nazis, after all did not invent anti-Semitism. Some of the early reflections on the Holocaust have attempted to present it as an aberration. The first plaque to mark the destruction of the Mosbacher synagogue refers to the ‘Rassenwahn’, or Racist madness’. This plaque has since been replaced.

Massacres of Jews in medieval Germany were not uncommon. One form they took was the ‘blood libel’ and the most infamous of these was the killing of the so-called St Werner of Oberwesel in the Rhineland. Werner was a sixteen-year-old boy said to have been murdered by local Jews who wanted to use his blood in a Passover ritual. The story, whose details are bizarre and implausible, nevertheless led to massacres of Jews up and down the Rhine.

Actually, the whole idea that Jews had some kind of desire to murder little boys, came from England. William of Norwich (1144), Harold of Gloucester (1168), Robert of Bury (1181) and High of Lincoln (1255) were all boys allegedly killed by Jews and in all cases their deaths led to the torture, execution and murder of Jews and other measures against them culminating in their expulsion from England.

Kristallnacht was essentially a re-run of these medieval Jew hunts. Its apparent trigger was the assassination of a German diplomat by a German-born Polish Jew living in Paris. This was said to have prompted attacks on Jewish communities across Germany which the Nazi government presented very much as a popular action, although their organisations were very active in co-ordinating the attacks behind the scenes and in ensuring that police and fire departments did not obstruct them. Just like in the Middle Ages, a crime or an allegation of a crime, was seen to justify attacks on all Jews.

I still remember the depiction of Kristallnacht in the Holocaust TV programme. It made a big impression on me then, especially, the collusion between state terror and street violence, the openness with which the attacks were carried out and the vulnerability and defencelessness of the minority being attacked – all these aspects were lodged in my mind.

A few years after the TV programme was made, I was able to read in my grandfather’s memoirs what he saw on the night of Kristallnacht and the morning after. For him, looking at it all with hindsight, it was the decisive moment when the Holocaust stepped into the open. A deeply significant event.

And because it is a deeply significant event which forms part of my personal remembrance picture, I look at present day events through the lens of Kristallnacht. And the present-day events I am looking at are the anti-immigrant riots that have taken place in England in the summers of 2024 and 2025.

What we have seen on the streets of England is like Kristallnacht in some ways, although not in others. The obvious similarity is the way in which the mere rumour that the murderer of little girls in Southport in 2024 was a Muslim and an asylum seeker led to attacks on mosques and former hotels converted to house asylum seekers. And again in 2025, the arrest of asylum seekers for suspected sexual assaults led to demonstrations against all asylum seekers. The idea that a crime committed by a member of a particular group justifies an attack against that whole group may seem medieval, something that Monty Python might lampoon in their film King Arthur and the Holy Grail, but it is a modern phenomenon, as we see in Kristallnacht and in Britain today.

The key difference between Kristallnacht in 1938 and England in 2024/25, is that today in the United Kingdom, the police are defending the rule of law and that includes defending mosques and asylum seeker hostels.

And in 2024, the government was clear that it opposed the rioters. Prisons were cleared to make way for rioters to be arrested, tried and imprisoned, including those who had incited violence online. In 2025, the political situation is somewhat different. Across a wide political spectrum, the threats of violence towards whole groups based on the crimes or alleged crimes of individuals is not being called out. Rather, we see politicians wanting to signal that they understand ‘concerns’ that people have and, in doing so, they validate these ‘concerns’.

What will happen after the next general election if the government changes? Depending on the outcome of the election, there may be an increase in the confidence of those who wish to instigate these riots. How far will the violence go? How will policing of these riots be affected by a change of government?

When I ask these questions, I am not asking them in a complete vacuum. Rather, I am asking them in a context in which a number of historical events have been identified as worthy to join a canon of remembrance events on the basis of their significance. For me, Kristallnacht, is one of these events.

What my visit to Neckarelz showed me was that a community can change what it chooses to remember. The events that a society attributes significance to are not set in stone even if some of the stone monuments remain standing. Societies choose which aspects of history they attach significance to. And they keep attaching significance to new things. And groups of people in these societies, like the KZ Gedenkstätte Neckarelz and the Museum in Mosbach, come together to work hard to make these changes in remembrance happen.

How do we know what the right things to remember are? We remember those things which will help future generations live in the right way. Let me end with the words of Jürgen Galm, Mayor of Osterburken. He wrote an introduction to an astonishing collection of eyewitness accounts of the end of WW2 in the town of Osterburken which included the liberation of a train full of prisoners from the concentration camp in Neckarelz. The collection forms part of the work of KZ Gedenkstätte and was published in 2022. Jürgen Galm wrote this: ‘My wish for us all is that the remembrance of past injustices sharpens our understanding of the value of democracy, human rights and the rule of law.’

That is my wish also. These are things that are important to me and I want my children and grandchildren to will enjoy their value also. How will remembrance evolve in Britain so that we attach significance to those things which will help future generations preserve these values by which we hope future generations will be able to live together?

A very powerful and moving piece. I think you are right to connect the Kristallnacht to the attacks on refugees in the Uk. The Nazis started slowly, with attacks and more and more discrimination, eventually moving on to genocide. Uplifting to hear about the new memorial.

Beautiful and very introspective piece.

As we’ve seen in the Balkans, people do have tendencies to remember not everytying worth remembering. A complex question.

I very much like the set up in Gedenkstätte you described. At first sight, playground next to a concentration camp looks extreme, but perhaps not so. There is a relatively new movie out, called The Zone of Interest, where a similar situation is described. Worth a watch.

As for persecutions, past and present, I would say the only difference today is social media, with its speed and sometimes taken for granted truthfulness. The rest is the same. Mass ignorance.

Thank you Zeljko. Social media massively changes the world we live in. I am finding, writing this blog that it makes it possible for me to find out about things that I would never have found out about if I had to go to a library and find a relevant book like in the old days (although I have been finding out some interesting things in libraries). So as well as mass ignorance, we have the possibility of making connections between things that would have previously been obscured to us. (Just to be a bit positive!!!)

Thank you, Robin, for this valuable piece of writing.

When we commemorate those who gave their lives in two World Wars, I often think we should also honour those who survived to endure a life of suffering. There are two groups in particular, the men who came home but so damaged, physically or mentally, that they were never the same again, and the bereaved, the widows and parents (and fiancés) of men who died, all of whom suffered from their loss for years afterwards. Future generations should be reminded of All the victims, and recognise the futility of war and the untold suffering it brings.

Thank you Jean. I notice that the Royal British Legion has recently expanded its definition of who is being remembered to include civilians. I read recently that army slang has a word for civilians, meaning civilians back home in Britain, and civilians, meaning civilians living in the theatre of war. But the Royal British Legion’s website does not make this distinction. I think this is a new development.

Interesting: As a History teacher, I have just returned from a trip I regularly make with with 6th Form students to visit Auschwitz-Birkenau and Krakow. In the past I have also led trips to Berlin where we have visited the Jewish museum and the Wannsee villa where the decision was made to execute the Final Solution. Although the Polish and German experiences of WW2 were obviously very different, I am always struck with the honesty and integrity with which these museums and memorials present their national narratives. In particular the visit to the Oskar Schindler factory in Krakow place great emphasis on the complex moral ambiguities of collaboration and by-standing that arose from living under Nazi occupation. I haven’t yet seen the same of sensitivity and honesty in the presentation of national narratives in France around the role of the Vichy regime or in Britain around the slave trade and empire.

Thank you for this complex and thoughtful reflection. Last night I was in Huddersfield for an event at the Holocaust North exhibition space. The event was organised by the local Unison branch. Speakers made the connection between the complicity of ordinary people in the events of the Holocaust and the current growth of attacks on migrant workers in the UK — many of them essential care workers, and working entirely legally, but still vulnerable to racist attacks and exploitation. The message I came away with was: Don’t let it happen here. A sobering thought.